Fairies and Spirits: Resisting Modernity

Part One: The Spirits Return

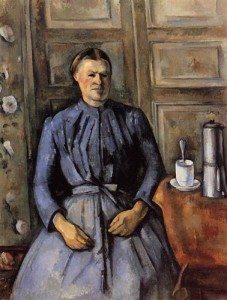

The English fin-de-siècle was quite different from the French fin-de-siècle. A mere glance at the art of London in comparison to that of Paris shows a French society racing ahead to the twentieth century and a British society looking backwards. This artistic state of affairs is completely paradoxical and unexpected. For the entire century ever since the British navy had routed the French fleet in the Battle of the Nine in 1798, Great Britain had been far more modern, far more industrialized, far more imperial than France. France had been loath to leave behind its history of hand-crafted labor, reluctant to engage in contemporary capitalism, and practiced modernité as fashion, which disguised an old culture balking at change. For France, the modern existed in the city of Paris but outside the city the old ways ruled. For England, however, the modern was everywhere and modern industrial cities such as Manchester and Birmingham spread across the midlands, while Liverpool and Glasgow swelled with global trade. But through the fantastical art of Lawrence Alma-Tadama and Frederic Leighton, British art drifted back to ancient times. Leighton’s famous Flaming June of 1895 is contemporaneous with Cézanne’s Woman with Coffee Pot, and the juxtaposition of these two paintings could be used by some to explain why the study of avant-garde art has been Franco-philic.

However, an examination of the larger British culture at the end of the century suggests that there is a story that is more complex than London falling behind Paris in the race to modern art. Leighton’s escapist vision of ancient Greece as seen in Flaming June was not an isolated phenomenon and can be seen as an aspect of Victorian penchant for fantasy which can be read as a counterpoint to the relentless modernism of real life. How else does one explain the Victorian belief in fairies and spirits? And, as tempting as it is to make fun of such convictions, intelligent people and leading pillars of society were very serious in their pursuit of the spirit realm and in their faith in fairies. The poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning was a believer. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was a believer. And even Charles Dickens, who spent a great deal of his time debunking spiritualists, made three ghosts the stars of his most beloved 1843 story, “A Christmas Carol.”

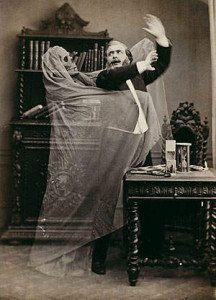

Fairies and gnomes and elves, spirits of dear departed ones, ghosts and beings from the beyond–all popular apparitions of the nineteenth century–were ancient folktales surviving into the modern era. These age old enchantments were resurrected from dustbins of the Age of Reason in order to re-enchant a world that had been disenchanted too soon. It is probably no accident that the chief residences of these otherworldly beings was England and America (mostly the east coast), the centers of the most intensive industrialization. It is also probably no coincidence that the earliest manifestations of spiritualism were the three Fox sisters from a small town in New York in 1848 the year of the First Wave of Feminism. In an age where women were barely allowed to leave the domestic domicile alone, they were ceded an advantage in being more spiritual and spiritualism or the ability to commune with spirits or go into trances became largely the domain of women. Thanks to spiritualism women were allowed to leave home and speak in public, arousing such anxieties that, strangely enough, spiritualism and suffrage were connected in the public mind. But in order to be legitimated, talking to the dead and even the possibility of the afterlife itself had to be “proven” scientifically and manifested as material evidence. The camera was enlisted in the quest to capture the spirits of the deceased and photographic tricks were used to turn the camera into a compliant instrument for fraud. Distraught individuals, mourning the loss of their loved ones, sought a memento of the beloved ghost and unscrupulous photographers were more than happy to oblige.

To our contemporary eyes, accustomed to PhotoShop, the many photographs of the “dead” are but superimpositions or double exposures or composite photographs. But these photographs fulfilled a need to believe in something more than the reality of physical life and its limitations. Perhaps the most eloquent explanations for this cultural need was articulated in 1917, in the midst of the Great War by the German philosopher Max Weber (1864–1920). One might have expected the evidence of technological and mechanical death to have cured any observers of any hope much less belief in life after death, but, to the contrary, the loss of life during the War was so great that spiritualism became stronger than ever. Although Weber did not speak directly of the war, he stated, in his famous essay, “Science as a Vocation,”

The increasing intellectualization and rationalization do not, therefore, indicate an increased and general knowledge of the conditions under which one lives. It means something else, namely, the knowledge or belief that if one but wished one could learn it at any time. Hence, it means that principally there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather that one can, in principle, master all things by calculation. This means that the world is disenchanted. One need no longer have recourse to magical means in order to master or implore the spirits, as did the savage, for whom such mysterious powers existed. Technical means and calculations perform the service. This above all is what intellectualization means.

It is at this point that Weber raises the idea of enchantment and the lack of enchantment by linking this “lack” to the utter finality of death.

Now, this process of disenchantment, which has continued to exist in Occidental culture for millennia, and, in general, this ‘progress,’ to which science belongs as a link and motive force, do they have any meanings that go beyond the purely practical and technical? You will find this question raised in the most principled form in the works of Leo Tolstoi. He came to raise the question in a peculiar way. All his broodings increasingly revolved around the problem of whether or not death is a meaningful phenomenon. And his answer was: for civilized man death has no meaning. Weber ends this essay with his famous observation: The fate of our times is characterized by rationalization and intellectualization and, above all, by the ‘disenchantment of the world.’ Precisely the ultimate and most sublime values have retreated from public life either into the transcendental realm of mystic life or into the brotherliness of direct and personal human relations.

In his well-known book, The Subject of Modernity, Anthony J. Cascardi explained that Weber connected capitalism and institutionalism and the rationalization of modern thought that separated the sacred and the secular. Cascardi noted that Weber understood this severance as a “value-conflict” or our “cultural fate.” As Weber said, “We live as did the ancients when their world was not as disenchanted of its gods an demons, one we live in a different sense..the bearing of man has been disenchanted and denuded of its mystical but inwardly genuine plasticity..” Decades after the cultural craze for spiritualism and naïve belief in spirit photography, Weber explained, not so much the actual practices of the mediums and the fortune tellers and those who claimed to go into trances, but the reasons why certain societies had need of such absurdities.

Eugène Thibault. Henri Robin and a Specter (1863)

Spirit photography in the late nineteenth century was aided by the huge loss of live during the Civil War in America and seems to have been an extension of the grieving process. Decades of mourning could sustain the fraudulent practice and there were many criminal cases and investigations undertaken on the part of the deluded bereaved. One of the most infamous cases was the notorious William H. Mumler (1832–1884), who is given “credit” for taking the first “official” photograph of a spirit. Prosecuted out of Boston, Mumler retreated to New York, where, undaunted, he reestablished himself as a photographer of the dead, who passed through him, lighting him up like a vacuum tube, as he explained it. Mumler was put on trial in New York but was acquitted and returned home to Boston, where, unbelievably, he returned to his lucrative occupation. According to Crista Cloutier in her article, “Mumler’s Ghosts,” one of his victims was none other than Mary Todd Lincoln who came to Mumler to be photographed for what is believed to be the last photograph of her life. Although he later claimed to have not known who she was, Mumler obliged her by capturing the spirit of her deceased husband tenderly standing behind her.

William H. Mumler. Mary Todd Lincoln (1871)

In his 2004 book, The Perfect Medium: Photography and the Occult, Clément Chéroux noted that spirit photography proliferated between 1870 and 1930, correlated with the end of the American Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War and the years of mourning following the Great War. This catalogue of an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art was reviewed by Stan Parchin who noted that the rise of amateur photography increased the sightings of ghosts who seemed to be happy to be photographed. He discussed the work of an unknown and ingenious photographer who captured the late Saint Bernadatte progressive fading away. As Parchin described, “One of the eeriest pictures from this period is The Ghost of Bernadette Soubirous (ca. 1890). Soubirous (1844-1879) was a sickly, French farm girl from rural Lourdes. She experienced eighteen visions of the Virgin Mary during her lifetime. By virtue of her simple and holy life, Bernadette was canonized, making her a saint of the Catholic Church in 1933. In the show’s haunting print, the viewer sees a garden outside of a building, perhaps religious in nature. The spectral image of a young woman, draped in a white robe and veil, peacefully proceeds to the left-hand side of the composition. Repeated five times with each impression becoming fainter, the “saint” gradually dissolves into the brick façade ahead, providing a convincing picture of Bernadette’s fleeting spirit, staged and photographed well after her death.”

Unknown Photographer. The Ghost of Bernadette Soubirous (1890)

The believers in the spiritual and in the magical were not credulous and uneducated people who were taken advantage of but prominent people who allowed–indeed welcomed–a fanciful mixture of folk tales and ancient suppressions to come into their lives, filling the vacuum left behind when traditional religious dogma was routed by Darwinian sciences that explained (disenchanted) the world through the powers of human reason and empirical measurement. None other than the extremely sharp mind and his presumably sharp eyes of Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930) were totally taken in by a series of photographs of fairies, claimed to have been taken by two young girls in York. As with spirit photography, the images were obviously fake, with the perpetrators themselves admitting that they had cut the fairies out of illustrated books, and yet, it took years before Victorian culture could be divested of its deep belief in fairy creatures.

As James Barrie, a believer, explained in Peter Pan (1904), “When the first baby laughed for the first time, its laugh broke into a thousand pieces, and they all went skipping about, and that was the beginning of fairies.” In the next post, fairy photography will be discussed.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.