Fairies and Spirits: Resisting Modernity

Part Two: The Fairies Arrive

In Strange and Secret Peoples. Fairies and Victorian Consciousness (1999), Carol Silver, explained that fairies were a uniquely English phenomenon, part of the folklore of the British Isles. The rise of a new interest in old beliefs in fairies coincided with the Romantic movement and the realization that modernity was pushing old ways into obscurity. Silver discussed a rather curious co-existence between a tendency to study the belief in fairies–through folklore and folklorists–and the scientific and Darwin-inspired desire to understand the scientific origin of who or what fairies may have been. “Impelled in part by political and nationalistic concerns, the English romantics began to explore their own supernatural heritage. Perhaps they felt the need to find rich fairy lore to compete with that of France and, later, Germany. French tales, both traditional and literary, dominated England, while..the research of the Brothers Grimm was universally admired. There was sense that fairies–utilized by Chaucer and redesigned by Shakespeare–were part of England’s precious heritage. Nostalgia for a fading British past was yet another factor. Many agreed with the poet-folklorist James Hogg that the fairies were leaving England. The nation was growing too industrialized and technological, too urban and material for their health and welfare. It became important to locate the fairies and chronicle their acs before they departed forever.”

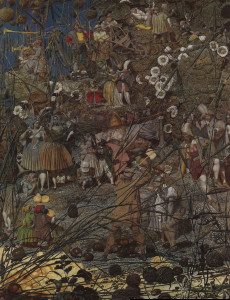

The idea of fairies “leaving” was a recurring one, linked to the spread of suburbs into what had been fairy territory, destroying their woodlands and lairs. Fanciful or not, the eradication of “fairy land” propelled the new field of folklore to catalogue all manner of fairy life, from changelings to fairy flowers. During the Victorian period, artists, from the Pre-Raphaelites on, devoted themselves to the genre of “fairy painting” for decades. Art history has buried this large body of visual culture and rendered it to a side show, but at the time, from the late nineteenth century to the early twentieth century, paintings of fairy fantasies were an enormously meaningful cultural phenomenon for the English. It is interesting to note that the fad for fairy lore coincides with the projects of documentary photographers such as John Thomson, and in her article “Victorian Fairy Painting,” Terri Windling underscored the contrast with the cataloguing of human types with the suggestion that “the wide-spread, casual use of medicines derived from opium no doubt played some part in the 19th-century taste for fantastic imagery.” The artist who is best remembered to day for fairy painting is, of course, Richard Dadd (1817-1886), who was quite mad, a murderer with a penchant for stabbing and a talent for recreating a fanciful and elaborate fairy world.

Richard Dadd. The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855–64)

But, for the purposes of this post, the most relevant of the many fairy painters were the Doyle brothers, Richard Doyle (1824-1883) and Charles Doyle (1832-1893), sons of the artist John Doyle, a political cartoonist known as “HB.” “Dickie” Doyle, who illustrated William Allingham’s In Fairyland (1870), was an eligible bachelor and seems to have been a decent enough person but Charles seems to have been delusional but treated as alcholic, whose one good deed, besides painting, seems to have been fathering Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), the literary inventor of Sherlock Holmes and the fervent believer in fairies and all manner of spirits. According to Silver, the popularity of retelling fairy tales to children resulted in both a watering down of fairies who were originally difficult pagan demons to tiny winged beings with benevolent intentions, suitable for a childish audience. Doyle illustrated charming fairies charmingly for innocent and credulous children. Although fairy tales tailored to the needs of children seems to be a harmless way to convey a national folklore and unique English beliefs, to adults of the Victorian era, this tradition had deep and complex cultural and psychological meanings.

In his classic foundational 1983 book, Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion, Jack Zipes discussed the changing role of fairy tales in European culture, tracing the origin of such stories, based in an upending of the social order through magic, to their evolution as fables intended to teach morals to children. Drawing on the concept of a political reading of fairy tales, Michael Newton commented, “Images of he political imbue the fairy tale. Even a cursory reading of the tales would show how fascinated they are with ideas of authority, power and rule. The stalk simplified political world of these tales offer satirical but also symbolic representations of power and inheritance.” In his introduction to the 2015 compilation of Victorian Fairy Tales, Newton made the insightful comment that fairy tales written by Victorian authors resemble Victorian England. And this tendency to place a timeless world, however, unconsciously, in one’s own modern era, raised another question–in England, the adult need for fairy tales was apparently so great that there was literary confusion as to whom fairy tales were intended–adults or children? As Nicola Bown explained in Fairies in Nineteenth-Century Art and Literature, there is great sadness underlying the fascination with fairies. Certainly, one can link the serious study of the belief in a parallel world existing on the edges of our own, just out of the corner of our eyes with the collection of vanishing folk tales but fairies are all about loss. “It is because the modern world in which they lived and which they had made was anonymous, uncertain and disenchanted teat the Victorians dreamed of fairies, whose enchanted world gave back the things they seemed to have lost. The idea of fairies’ farewell acquired such poignancy at the end of the century because it represented an anxiety that the condition of being modern was now so acute that no possibility of enchantment could offer consolation for it. If we forget the fairies, thought the victorians, they will die, and then there will be no magic left in the world..” It was the Victorians who invented the modern notions childhood, an extended period of suspension between helplessness and usefulness possible only for well-to-do families. Class issues aside, childhood as a social institution was also an expression of and an acting out of adult anxieties over their collective roles in wiping out an old way of life. Being a child meant having no responsibilities and living outside of linear time. Through fairies, adults could stop time and return to childhood and find enchantment once again. Bown discussed the difficulty of painting nostalgically in an age in which representing fairies was challenged by a loss of faith, resulting in a certain shallowness of meaning. Perhaps the nostalgic longing for a lost past could be quenched only with “proof” or photographs.

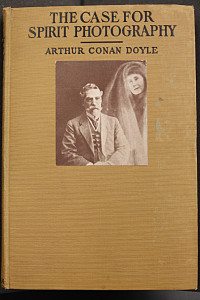

As lovingly recreated in the 1997 film FairyTale. A True Story, the discovery that fairies were living in the Yorkshire village of Cottingley and that some of these fairies had consented to be photographed by two young girls needs to be understood against the backdrop of the Great War (1914-1918).In the midst of a terrible war, the poet Rose Amy Fyleman (1877–1957) wrote Fairies which began, “There are fairies at the bottom of our garden!It’s not so very, very far away;You pass the gardner’s shed and you just keep straight ahead –I do so hope they’ve really come to stay.” It was this poem that connected the rich and famous writer of detective stories to the hunt for fairies. Arthur Conan Doyle was in his fifties when the Great War began and he lost his son, friends and relatives. Like many individuals in England, his life had been torn apart by this war, and, like many grieving relatives, he turned to spiritualism. Belief in the spirit world was hardly to Doyle. A former doctor turned writer, Doyle had left religion behind when he was young and immersed himself in spiritualism. Although we know him best as the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Doyle actually wrote twenty books on the spirit world.

Today, our entry into spiritualism is usually imaginative movies that are escapist fare not to be taken seriously. But for Doyle and a large portion of post-war society, the spirit world had to be real for the possibility of the appearance of the ghosts of loved ones was a crucial part of a passage through grief. His own wife, Jean, was a medium in her own right. The practitioners of spiritualism regarded photography as an intrinsic part of the quest to “prove” that spirits were among us and Sir Arthur was photographed with his son–lost in the War–hovering near him. For Doyle fairies were a part of this world of the supernatural, and when the Cottingley photographs were published in 1920, he immediately rallied to the images, which he considered further proof of the spirits among us. The fact that these photographs were taken by two young girls, cousins, was of vital importance to Doyle. Doyle had a low opinion of women and was deeply opposed to women’s suffrage and thus could not imagine that any young girl would have had the intellectual or technological capacity to fake a photograph. But the fairy photographs were fake and a young girl faked them.

Frances and the Fairies (1917)

The year of what was essentially a photographic project was 1917. Outside the suburbs and countryside of England, a war was raging. The photographer was Elsie Wright, the daughter of a man with a camera and she posed her cousin, Frances Griffiths, from South Africa with some fairies, and Frances photographed Elsie in turn with other fairies–all of which had been copied from drawings by Arthur Shepperson in one of the many books for children, Princess Mary’s Gift Book. Frances sent one of the images to a friend at home, explaining, it was “me with some fairies up the beck..”(stream) Elsie and I are very friendly with the beck Fairies. It is funny I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there. The father was amused, and there the matter might have rested, except for one fact–the mother, Polly Wright, believed in Theosophy and was a follower of Madame Helena Blavatsky and, after a lecture on fairies for the Theosophical Society in Bradford, she mentioned her daughter’s fairy photographs. This story of a rare event–photographing fairies–came to the attention of Theosophist Edward Gardner, who came to the attention of Doyle who was writing a story on fairies for Strand Magazine for Christmas in 1920 and needed illustrations. Three years after the execution, credulous adults were involved with the work of two young girls who had created a fantasy and were ensnared in the world of adults who desperately needed to believe.

Elise and the Gnome (1917)

Gardner and Doyle wanted more photographs but the father had taken the camera away from the young girls. Gardner traveled to Cottingley with a new camera. Frances who was now living with her parents in Scarborough, was reunited with Elsie and, as a result of the visit, three more photographs of fairies were somehow produced and the plates were carefully shipped off to London. Despite doubts on the part of many experts, Gardner and Doyle were convinced–or convinced themselves that the photographs were real. As Doyle said, “When our fairies are admitted other psychic phenomena will find a more ready acceptance..” and indeed, it is understandable that there was an entire generation, stunned by modernity and stripped of its faith by War desperately needed these shreds of hope in an afterlife and in another magical world of fairies.

Elsie and the Fairies (1920)

In 1922 Doyle used the photographs to illustrate The Coming of the Fairies. But hoping does not make it so. The fact that the girls, when they grew up, confessed that the photographs were fake and described how they created the illusion of stylish creatures with wings did not deter many of the true believers. The young ladies had to live for the rest of their lives with their childhood tricks with a camera, but the desire to believe was so strong that it was not until 1978 that the myth of the fairy photographs was debunked and in the early 1980s Elsie confessed to the hoax. The fairies were finally put to rest. Arthur Conan Doyle died in 1930, convinced to the end that there were fairies in the world.

The Fairies (1920)

As Peter Pan beseeched his audience in James M. Barrie’s 1904 play, “Do you believe in fairies?…If you believe, clap your hands!”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.