The Annans, Father and Son

From Document to Art

Around 1890 the world of photographers changed. Before the end of the nineteenth century, photography had been very much an individual enterprise. The practitioner, whether amateur or professional customarily was responsible for obtaining supplies,from emulsion to plates of glass to paper to cameras. Businesses which dealt in large volumes of photographic production, such as that of Matthew Brady, simply scaled up. The result of such localism and individualism was inefficiencies and lack of standardization, but this very lack of uniformity allowed those inclined to experiment to do so with total freedom. Until the fin-de-siècle era, photography was prized largely for its role as being a handmaiden to science or to empirical studies, providing irrefutable evidence of the facts on the ground, the immediate and material truths. The cultural context of positivism which ruled most of the nineteenth century determined not so much the use of photography but its meaning–a photograph was to be believed. Even though it was widely known that a photograph could be faked, indeed one of the first photographs was staged and many of the combination printings were recognizably inauthentic, a photograph, any photograph, was entangled in the belief system that the camera was a machine the recorded that which existed. But this social assumption which limited the meaning and the purpose of photography was unsettled by the unintentional consequences of the actions of an American entrepreneur named George Eastman (1854-1952).

Eastman, who revolutionized the craft of making photographs by turning hand work into a corporate business, was not a photographer. He was a business person who understood that a skill known by a large number of people who replicated each other’s efforts, alone in their separate studios, could in fact be streamlined. By taking a horizontal activity with many unique steps and turning the act of taking a picture into a vertical business, Eastman removed the science of making from the hands of individual photographers and locked away any changes that advanced photography in the legal maze of a patent system. Within a few years, Eastman not only folded the film and the development of the film into a camera–all under his control–he also created, almost overnight, millions of new photographers. By the year 1900, there were three groups of photographers–commercial photographers, the general public and that small and exclusive group, called “amateurs,” who created photographs the way a painter created a painting and who dabbled in experiments with the materiality of a photograph. Eastman was aware of this small group of elites and was interested in selling them his products, such as his paper, but he was probably unaware of the extent to which his business altered their pleasure. Pushed out of the cozy world of experimenting with chemistry, the amateur photographers were faced with an existential crisis. Who were they? Scientists or artists? What should a photograph exhibit? Technical excellence or artistic merit? The debate was existential to be sure, it was definitional, and the soul-searching was also generational.

The new generation seceded or broke away, left behind their forefathers and the scientific aura that had inspired them. The younger photographers embarked on what would be a decades long struggle to establish photography as art. Given the decades long connection between a photograph and evidence–a connection that still holds somewhat true today–it would be a long and difficult task to convince an unwilling art world that a photograph could be a work of art. In 1892, Henry Peach Robinson (1839-1901) wrote, “If photography is ever to take its proper position as art, it must detach itself from science and live a separate existence.” Even as the work of the early twentieth century “amateur” artist in photography appeared to narrow, the range of artistic photography opened. An interesting example of subtle shifts in photographic meaning is a comparison between two generation of photographers, father and son, at the moment when the same subject can be realized first as a document and second as a work of art.

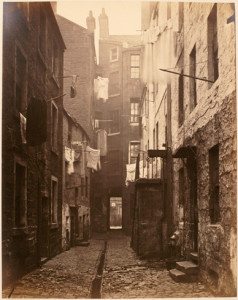

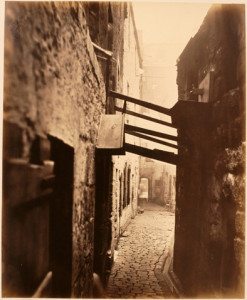

Precisely because it seems to have artistic aspirations, the photographic work of Thomas Annan (1829–1887) presented a very real problem for documentary photography. He was a successful commercial photographer in Glasgow, a city that had been awakened from its Scottish obscurity in the nineteenth century by global trade in cotton and tobacco, various chemicals, soap and paper. Tripling its population in just a few decades, the city was also a site of industrialization, shipbuilding and locomotive manufacturing. The results were predictable and repeated across Great Britain: a huge wealth gap between the owner class and the working class, insufficient attention paid to public health and housing, and widespread of the many while the few made fortunes exploiting the lower classes. It is this untenable social situation that Thomas Annan was asked by the Glasgow City Improvement Trust to depict. The Trust, a small and ultimately powerless, government department hoped to tear down slums, which were very profitable for the owners, and needed photographs which revealed the tragic truth of living conditions in Glasgow. The photographs taken by Annan showed old and picturesquely aged buildings, almost devoid of human inhabitants, and thus wiped clean of suffering. The photographer’s rather bloodless documentation of what was a human catastrophe, on par with that which was represented by Gustave Doré in London and Jacob Riis in New York. This 1868-1871 project on the part of Annan keeps a distance between the photographer and the people who lived in these alleys, but, this remoteness is not surprising, considering that the exposure times were eleven minutes.

Thomas Annan. Close. No. 29 Gallowgate (1872)

Annan’s final images were poetic, beautiful, haunting, exquisitely produced and empty of the social “truth” of Glasgow, as told by Frederich Engels in his 1845 book, Conditions of the Working Class in England of 1844,

“I have seen human degradation in some of its worst phases, both in England and abroad, but I can advisedly say, that I did not believe, until I visited the wynds of Glasgow, that so large an amount of filth, crime, misery, and disease existed in one spot in any civilised country. The wynds consist of long lanes, so narrow that a cart could with difficulty pass along them; out of these open the ‘closes’, which are courts about fifteen or twenty feet square, round which the houses, mostly three or four storeys high, are built; the centre of the court is the dunghill, which probably is the most lucrative part of the estate to the laird in most instances, and which it would consequently be esteemed an invasion of the rights of property to remove. In the lower lodging houses, ten, twelve, or sometimes twenty persons, of both sexes and all ages, sleep promiscuously on the floor in different degrees of nakedness. These places are generally, as regards dirt, damp, and decay, such as no person of common humanity would stable his horse in.”

As Wolfgang Kemp pointed out in his 2014 article, “Images of Decay: Photography in the Picturesque Tradition,” in comparison to Doré’s “apocalyptic vision of London after dark,” Annan’s project was less activist and more preservationist. Slated for demolition, these slums were already consigned to history and, since albums containing the photographs of the buildings were given as gifts, the project to preserve their photographic memory was benign. As Kemp stated, “The primary interest of the photographs at this time was as local history.” Indeed, the slums photographed by Annan were torn down in 1871, removed as eyesores but retained as part of the historical memory of the city. The project, from its very inception, was ambiguous and problematic, but the ambivalence may be felt more keenly by a contemporary audience critical of social injustices. In his own time, Thomas Annan did not explain his or the motives of the Trust, a silence that was interesting considering the copious literature on the horrors of the slums of Glasgow.

Thomas Annan. Close, No. 83 High Street (1872)

To add to the confusion between picturesque photography and documentary images, the son, James Craig Annan, reprinted the images of Old Closes and Streets of Glasgow (1868) in 1900 as photogravures or engravings of the original photographs taken from a plate prepared by photographic methods. These beautiful images were allowed to exist on their own in this limited edition volume, which like the first albums were lacking in explanation. The continued silence on the part of the son further relegated the images to the realm of art, after the (documentary) fact and they were reprinted in Alfred Stieglitz’s exquisitely produced photo-journal Camera Work in the art context of The Brotherhood of the Linked Ring, of which James Craig Annan (1864-1946) was a part, Pictorialism and Photo-Secession in New York.

In the book Thomas Annan of Glasgow. Pioneer of the Documentary Photograph (2015) by Lionel Gossman, the author wrested with confusion surrounding the work, which was reprinted in the photographer’s lifetime as carbon prints which were altered by his own hand–he added clouds and sharpened some of the linear elements. In his time, Annan was considered an “artist,” remarkable tile in the 1870s but indicative of the shifting attitudes towards photography. “Among Annan’s own contemporaries, the Reverend A. G. Forbes, author of the texts accompanying Photographs of Glasgow (1868), refers to him repeatedly as ‘our artist,'” and “a reviewer of a Photographic Society show in London described Annan’s landscapes as of such ‘high artistic merit’ that their creator “must rank amongst our first class artists.” In addition, we have Annan’s own words about his work, including the statement that “my constant aim is to make my Photographs like Pictures” and in 1884 he gave a lecture affirming “Art in Photo Landscapes.”

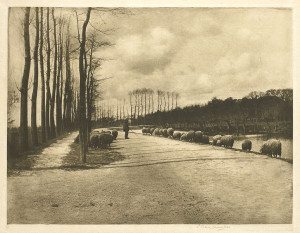

James Craig Annan. A Utrecht Pastorale (1892)

Trained by the inventor of the photogravure, the Viennese expert Karl Klič (1841-1926), the son inherited the father’s business and was mainly active in the craft of photogravure. However, James Craig Annan soon established himself as a photographer in his own right, and given his expertise in photogravure it is no surprise that he gravitated to the prints of James Whistler and the atmospheric tradition of Dutch landscape painting. It is illustrative of the extent to which the mindset of photographers had shifted that Annan’s first photographic journey to Holland was in the company of an artist, David Young Cameron. But, unlike the older generation that preferred the view camera and even the old fashioned glass plates, the younger Annan worked with the hand-held camera and its fast film. Although the camera’s technology allowed him to capture a moment in time–rather like Impressionism–his work does perhaps predict the “decisive moment” philosophy that characterized photography later in the century that novelty is not his intention. That said, the type of camera used by Annan allowed him to capture dramatic moments that equated what had been done in painting. Cameron, a printmaker, and Annan, a photographer, exhibited their respective version of Dutch landscapes together, further linking photography with art in the Glasgow exhibition in 1892. This photographer was essentially a re-photographer, having re-produced the work of Hill and Adamson and his own father’s photographs as photogravures, and Annan’s work can be seen as a re-interpretation of Whistler and the Impressionists re-imagined through a small camera. The formalization and the freezing of the landscapes caught by Annan was intensified by the final step which was a conversion into the photogravure, which allowed for the translation of a mechanical process into an artistic one. The hand of the artist is clearly present.

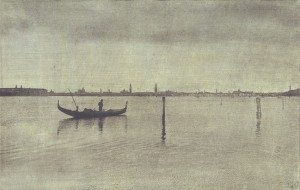

James Craig Annan. Venice from the Lido (1894)

The work of James Craig Annan, then, was tailor made for the shift from documentation to art and after his trip to Italy and his homage to Whistler in 1894, Annan was elected to The Brotherhood of the Linked Ring, joining an international network of photographers dedicated to art. He exhibited the Venice works as photogravures in the association’s Second Salon and published a portfolio entitled, Venice and Lombardy. A Series of Original Photogravures. Annan rejected the use of the stereograph in photography–“a scientific toy”–and felt that artistic photographers (such as himself) were guided by “observing the works of men of genius in all departments of the fine arts.” But Annan was modern in his use of the small quick camera: he developed a keen eye for chance and for the brief opportunity presented by nature. He always sought beauty, but was able to photograph what his father would not or could not–the people of Venice, from high to low–and it seems that, as he continued to work as a photographer, Annan developed a photographer’s sharp opportunistic eye. He recorded his process which combined an understanding of the tradition of paining in terms of formal composition with the possibilities that quick film offered him: he could find a spot, compose an arrangement and then wait for something interesting to happen. The 2014 article, “The Aesthetics of British Pictorial Photography. Case Study: James Craig Annan’s Portfolio Venice and Lombardy,” by Gabriella Bologna noted that Thomas Annan photographed art works, paintings, to be reproduced and that James inherited that aspect of the business, indicating an intimate knowledge of art that few artistic photographers possessed. Like his father’s work, the photography of James Craig Annan was poised in an in between zone. Just as his father’s photographs were and were not examples of documentary photography, his images were and were not photographs. Annan’s work, occupying uneasy spaces, were symptoms of the internal arguments and debates roiling the world of art photography–how can a photograph be transformed into a work of art?

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.