Cubism After Cubism

Paris Coming to Order, Part One

What happened to Cubism? Before the Great War broke out, the movement seemed to be dominant, even hegemonic in Paris, but after the War was over, Cubism was history. In other words, the Great War nothing would ever be the same, the culture had been moved, as if by a gigantic quake, out of the lingering nineteenth century. By 1918, almost twenty years too late, the shock of the modern pushed the decade into the early twentieth century. While the larger culture, the wider society adapted to the presence of technology and accelerated change, accepting the present and even the uncertain future, the art world in Paris turned inward and went backward and became conservative. The rising poet Jean Cocteau (1889-1963) coined a term that became the phrase for the retreat that characterized the 1920s in Paris. He called for a rappel à l’ordre, or a recall to order, a return to the order of classicism in his 1923 book Le Rappel à l‘ordre. As early as 1920, Cocteau discovered, while reading the poets. who lived before Baudelaire’s profound transformation of poetry, the virtues of rhyming, simplicity, and figuration rather than Symbolist evocation. Working with his creative partner, Raymond Radiguet (1903-1923), the poet sought to create a timeless style. The couple began a short-lived magazine Le Coq in 1920 and the goal of the six issues was a “return” to the past in reaction to the post-war fascination with the “machine.” “Return to Poetry. Disappearance of the Skyscraper. Reappearance of the Rose” was their slogan.

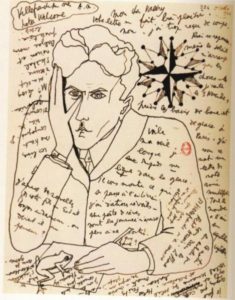

Jean Cocteau. Self-Portrait in A Letter To Paul Valéry (1924)

The “return to order,” sometimes termed the “recall to order,” was based upon the confused conviction on the part of the public that Cubism itself was German. The anti-Cubist wave was intensified during the War and, after the War, Cubism was stranded on the hill of anti-German sentiments. Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) himself appeared to be adjusting to the new current and during the War, moved away from Cubism. The avant-garde artists held what historian Larry Witham termed “a patriotic exhibition” in 1916. As he pointed out in Picasso and the Chess Player: Pablo Picasso, Marcel Duchamp, and the Battle for the Soul of Modern Art, although the former art audience was largely uninterested in art and consumed with the War itself, the exhibition “The Modern Art in France,” was notable for the first public appearance of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Those few who attended the show were uninterested in this now-famous work. After the war, the anti-Cubism sentiment was symptomatic of and part of a larger push towards conservative politics and Cocteau fashioned himself as “right wing.” While Cocteau was an odd messenger for conservativism— in 1915, he ingratiated himself to Picasso by dressing like a Harlequin for a studio visit—by 1920 he was a notorious and rebellious poet, whose demand for a “return” to poetic traditions summed up the post-war mood. After every war, there is always a sentiment of longing and nostalgia for the familiarity of the past before the world was irrevocably altered, and Cocteau’s sentiments seemed to be a recipe for healing. Based upon logic and order and rational thinking, the classicism of which he spoke was considered distinctly and uniquely French, the kind of classicism familiar in the Baroque paintings of Poussin.

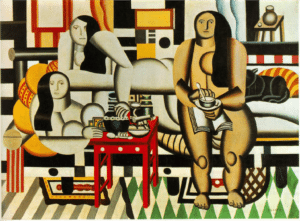

Fernand Léger. Three Women (1921-2)

During the war, the Cubist artist Fernand Léger (1881-1955) had served in the engineering corps on the front at Verdun, where he was gassed. Hospitalized for two years, he worked through his battlefield traumas with art, which became more figurative and more conservative to graphically convey the horrors of the battlefield. In her book, When Paris Sizzled: The 1920s Paris of Hemingway, Chanel, Cocteau, Cole Porter, Josephine Baker, and Their Friends, Mary McAuliffe wrote of this artist and his mood at the end of the War:

“Peace,” the painter Fernand Léger exultantly wrote his good friend, the painter André Mare. Léger had been severely gassed while serving at Verdun, and Mare was badly wounded on the Picardy front while camouflaging artillery with Cubist designs. “Finally,” Léger went on, “after four long years, exasperated, keyed-up, depersonalized man opens his eyes, takes a look, relaxes and rediscovers life, gripped by a wild desire to dance, let off steam, scream, at long last stand upright, shout, scream and squander.” Keenly attuned to the moment, he added, “A hurricane of life forces fills the world.”

By 1920, a calm seems to have descended upon Léger who smoothed the waters of his early agitated Cubism with a new and elegant classicism. The most famous work of this new direction was Le Grand Dejeuner of 1921, a direct homage to Ingres and the French tradition of the grande nu. Constructed on a frankly expressed grid, the painting is stilled and rational, imposing order upon a complex and cluttered modern interior where three inexplicably naked women are having lunch. The work of a wounded veteran recovering from battle, this painting exemplified Léger’s return to order and society’s slow settling into a period of peace following a time of turmoil. Picasso, however, was not impressed with this strange combination of the classical with the new Machine Aesthetic, and, almost as if he was frozen in transition, did very little painting during the War. Picasso was not alone and there were allies in Rome. As Charlene Spretnak related in The Spiritual Dynamic in Modern Art: Art History Reconsidered, 1800 to the Present, Mario Broglio, a painter, began a magazine of “plastic values” called Valori plastici in Rome. Broglio demanded a return to realism, figuration, the timeless topics of still lives and landscapes based in the timelessness of classicism. The classicism referred to was literally a resumption of the antique classical art of the Greco-Roman tradition and Witham noted Picasso’s friendship with Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), the Italian Metaphysical artist. Their friendship had begun before the War while the Italian artist was living and working in Paris and resumed during the War when de Chirico returned, after escaping the clutches of the Italian army. The “returns” to classicism were, of course, different in France than in Italy. In Italy the term “valori plastici” meant exactly how it translates–“plastic values” referring the strong forms of the early Italian Renaissance, such as those of Giotto. If the reaction against the avant-garde in Paris was a rejection of Cubism and pre-war disorder, in Rome, the abandonment of Futurism was a refusal to accept the eclectic historicism and diluted and misused classicism of the Vittorio Emanuele wedding cake at the heart of Rome and the disorderly avant-garde art that sought to replace the past.

Giorgio de Chirico. The Soothsayer’s Recompense (1913)

Picasso’s move to classicism began as a slow turning away from Cubism even before the War, and it is generally conceded that Picasso and Braque were leaving atelier experimentation behind in favor of a version of Cubism that was more “decorative.” The last few months of their partnership was marked by a series of paintings that were delightfully dotted and frankly charming, in a rococo fashion. This final flourish of their partnership predicted that the real future of the second stage of Cubism would be the realization of its decorative potentials, played out in Art Deco. In 1917, Picasso began the exploration of Cubism as design or an applied art when he joined the group of outstanding performing artists participating in a revolutionary wartime production of the Ballets Russes in Rome. Presented by Sergei Diaghilev, based on a story by Jean Cocteau, with music by Eric Satie and choreography by Léonid Messine, Parade was a modern ballet made remarkable by Picasso’s set designs, his extraordinary stage curtain, and his inventive costumes. The Harlequin, once part of his Rose Period, returned as a building as if to announce a rethinking and the artist’s embarkation on a new style. Set in Paris, Parade was Picasso’s final farewell to Cubism, and his definitive parting from Braque, who was operating a machine gun on the Western Front. The costumes of the characters, human and animal, were Cubist collages manifested in three dimensions and set in motion. The revolutionary and whimsical play debuted on May 18, 1917, Théâtre de Châtelet and at a loss for words, the poet Guillaume Apollinaire termed the performance “surrealist.” For Picasso, Parade was a way out of Cubism, for the Salon Cubists, this new direction towards design was a way back into Cubism—Cubism could become an applied art.

Pablo Picasso. The American Manager (1917)

Before the war Cubism had been divided into parts: those artists who showed in the public salons, the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Indépendants, and were therefore called the “Salon Cubists;” and Picasso and Braque who used their dealer, Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler to sell directly to clients, usually in Germany or Russia. The Salon Cubists and Kahnweiler’s artists, whom he insisted were not “Cubists,” were separated from their colleagues by where they showed their art. Braque and Picasso showed in Kahnweiler’s small gallery and the Salon Cubists, as the name implies, exhibited in the large sprawling salons open to the public. Thanks to the ample newspaper coverage that accompanied the Salon d’Automne and the Salon des Indepenéants, in the pre-war years, the Salon Cubists were famous, even heroes, standing firm against critical disdain and public protest, but the War scattered them to the four winds. Fernand Léger and Georges Braque (1882-1963) both served in the French Army, engaged in active combat, while many of their colleagues were in the camouflage corps. Albert Gleizes served for one year and then spent the rest of the war in New York City where he joined Marcel Duchamp, who had earlier taken himself out of the art game. Duchamp’s brother, Raymond Duchamp-Villon was in the military and died of blood poisoning at the end of the war. His other brother, Jacques Villon, whose real name was Gaston Duchamp, also served in the army, as did Jean Metzinger. However, Henri le Fauconnier went to Holland and waited for the conflict to end, staying in the neutral nation well beyond the end of the War. Two major artists remained in Paris, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Like Juan Gris, who also remained in place, Picasso was from Spain and therefore outside the reach of the French draft. Matisse was simply too old for service. These artists continued their work, enjoying an uninterrupted stretch of creative development. Both Picasso and Matisse moved beyond Cubism and Fauvism, running ahead of the artists who were away at war. When the War was over, their former colleagues had to pick up their careers and put their lives back together, and they did so in the shadows of Picasso and Matisse, now major artists, stars who now outranked them and had moved on to new ideas. Picasso and Léger away from Cubism signaled the return to the order of classicism, while the Salon Cubists sought to revive pre-war Cubism and make it respectable. The route the rebirth of Cubism was a monetary one.

Georges Braque. The Round Table (1929)

The end of the war meant that the previous dissension over avant-garde art was now a settled matter and the once-unfamiliar art had acquired value. The idea that innovative art was valuable in the financial sense gave rise to a healthy art market in Paris after the War, and this was the real order that settled over the art world. Art should appeal to the now willing collectors, who wanted to invest in the avant-garde, but what they wanted was the work of a major artist that was recognizable, in other words, the signature style should be present, but what was disruptive before the war needed to be tamed for this growing audience. For the returning Cubist artists, modern art was Cubism and they carried on as they had before the War. Their stance may have seemed regressive, but their post-war Cubism continued with what was now a historical style. Their efforts were, in effect, a “return to order.” To return to order, post-war Cubism had to become more “classical” or more conservative to appeal to new patrons. When Georges Braque returned to the Parisian art scene, it was after serving on the front, being gravely wounded, and after undergoing a long recovery. The partnership with Picasso was broken, simply because the two men could no longer share their experiences. Their lives had gone in two different directions. The Cubism of Picasso and Braque no longer existed. While Picasso turned to the classical and conservative in the 1920s and Braque settled on a variation of Cubist collage, painting the elements instead of pasting paper on a support. As if seeking comfort in the familiar, for the rest of his life Braque painted endless variations on the still life on the guéridon, a small circular top table. It was Braque along with the Salon Cubists who inherited Cubism and carried it on to its new destiny in the years between the Wars. But this rescue was not the work of the artists on their own; they had the able help of the Rosenberg brothers–Paul and Léonce–the art dealers who knew how to market the past and make historical art valuable again.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.