Before Art Nouveau

Educating the Consumers for the “House Beautiful”

Before Industrial Design, was a practice that we today would refer to as “Product Design,” encompassing both “hard” goods and “soft goods” and home decoration. The concept of decorating the home had become increasingly significant, as the middle class achieved the means to purchase houses and to decorate them. The middle class preferred the time honored Victorian style, which, to the modern eye, was cluttered and dark. But there was a new trend stirring in Europe–something more open and cleaner lined, lighter is substance and color. The class of consumers interested in the Aesthetic Movement and the attempts to fight the supposed bad taste of mass-produced furnishings in England would have merged with ease into the various manifestations of new designs at the turn of the century. Perhaps due to the impact of William Morris and his Arts and Crafts Movement and James Whistler and the Aesthetic Movement, in England, there were several different versions of Art Nouveau. The more rectilinear style in Scotland with Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868-1928) was called the “Glasgow Style.” The “Glasgow Style” concentrated on architecture and furnishings for the anti-Victoria homes in Scotland. Around London proper, there was the “Liberty Style,” named after the Liberty fabrics. Arthur Lasenby Liberty (1843-1917), a business person, was as determined as William Morris to reform the interiors of Victorian homes.

Liberty Store on Regent Street

In 1875, Lasenby opened a famous shop in London on Regent Street. Taste maven and writer, Oscar Wilde stated that “Liberty is the chosen resort of the artistic shopper.” In fact Sir Arthur–he was knighted in 1913–said “I am afraid that in this and other aspects I have become a mere adjective.” As Sarah Nichols, author of “Arthur Lasenby Liberty: A Mere Adjective?” wrote, “..catalogues issued by the company as early as 1883 used the term “Liberty Art Fabrics,” and a furniture catalogue of around 1910 illustrated rooms designated as being in the Liberty style..” Nichols quoted from the magazine Fortunes Made in Business: Life Struggles of Successful People, “Libertyism, if it may be so called, is not a fad or a fashion, it is a firmly established movement, that touches the love of the artistic which is born in everyone of us, the taught and the untaught.” She also included a statement from a 1900 article in The Art Journal, “the Growth of an Influence:” “He has built up an influence that has laid hold of almost every section of society, and has been responsible for a style different in many ways from anything previously existing and has cultivated it until has gained an authority that is universally admired.”

Liberty Fabrics in an Interior

Liberty was closely allied with Walter Crane and George F. Watts, reformers of modern design, and was also part of the dress reform–referring to the decades long crusade to made women’s clothes more healthy and more intelligent. In fact when Liberty established himself in an independent business, the East India House, he specialized in “art fabrics from the Orient” and he also sold exotic goods from the East and sold these wares to his artist colleagues, Lord Leighton, Edmund Burne-Jones, Dante Rossetti, James Whistler and Edward Godwin. In fact, Godwin, a furniture designer who often designed furnishings with Whistler, became the first director of Liberty’s “costume department.” According to Patricia Cunningham, Liberty linked the “progress of taste in dress” to the progress of taste in manufacture, while Walter Crane stressed the significance of art education. In her book, Reforming Women’s Fashion, 1850-1920: Politics, Health, and Art, Cunningham explained that Liberty traced the taste for “reform dress” back to the discovery of Japanese fabrics and for the growing British demand for “softer draperies and daintier fabrics between the 1870 and 1880..He felt that the new aesthetic movement was a ‘fashion’ in which all canons of waste were forgotten or ignored. The year he referred to as 1881, so his references were to aesthetes who wore their artistic dress in public. By the turn of the century, however, Liberty felt that his ideas were taking hold and making an impact on fashionable dress.” The customers for Liberty fabrics and furnishings were informed through the Liberty catalogue that “what is good in current art is the outcome of earlier experiments and that there is nothing that is absolutely new–it is all a matter of evolution.” The firm established “Artistic Truth” or “designs which were good and true in principle.”

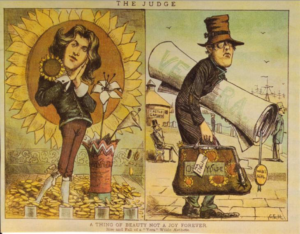

Oscar Wilde in New York in 1882 Taken by Napoleon Sarony

The last two decades of the nineteenth century were a prelude to the twentieth century and the struggle to wrest something “modern” out of the grasp of the “traditional.” Several terms were prominent during this transitional period: “reform,” which implied that fashion had gone wrong and had become delinquent and needed to be changed. To the idea of improvement should be added the necessity of “education,” that is educating the consumer and retraining the public’s eye and helping the shopper accept new products.The words “art” and “artistic” and “aesthetic” were frequently evoked, suggesting that artists and artistic minds had intervened into the worlds of fashion, home furnishings, and interior design to ‘reform” the Victorian home with art. The artist would intervene, injecting the “artistic.” The word “artistic” is significant, because the driving concept behind the British reform movement was that every home should be a work of art. However, not everyone understood “art,” or recognized the “artistic” and this is where the idea of art education entered. If consumers were not educated, they could not recognize good design, and if they could not recognize the artistry, they would not buy and would not consumer. Along with the eye, habits of a life time had to be changed. One of the most important disciples of modern design, Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), toured America, touting the “House Beautiful” in 1882, under the title “House Beautiful: The Practical Application of the Principles of Aesthetic Theory to Exterior and Interior House Decoration, with Observations upon Dress and Personal Ornaments.” Indeed, the concept of “beauty” drove the impulse to educate misguided people towards universal standards of good taste. Wilde had begun his continental tour with a theoretical approach which proved to be tedious for his audiences, so he changed his speeches to applied design, in other words, how to furnish one’s home in terms of good taste.

Age 27 Oscar Wilde arrived in New York stating,

“I have nothing to declare but my genius.”

Unfortunately, the “House Beautiful” lectures of Oscar Wilde have never been published. As a prominent member of the English Aesthetic Movement, and inheritor of the ideas of John Ruskin and William Morris, Wilde preached a paring down, a simplicity and introduced the idea of including only what was necessary to the home and cautioned his listeners to avoid nick-nicks. The term “house beautiful” emerged during Wilde’s American tour in 1882. In March in Chicago, Wilde lectured on “Interior and Exterior House Decoration,” a title which was altered in California a month later to “The House Beautiful.” The term remained for his entire American tour and continued to be used in England, Scotland and Ireland from 1883 to 1885. Wilde wanted his lecture to be more practical than theoretical. In order to explain how the term “beauty” or even “good taste” could be applied to the average middle class home. Wilde was a later generation than William Morris and was suspicious of the designer’s horror vacui approach, especially when it came to Morris’s intricate wallpaper. He said, “I have seen far more rooms spoiled by wallpapers than anything else: when everything is covered with a design the room is restless and the eye disturbed.” In reading Wilde’s essays, one can assume that he preferred painted walls, such as those pioneered by Whistler, in contrast to wallpaper. He admonished his American audience, “You have too many white walls. More colour is wanted. You should have such men as Whistler among you to teach you the beauty and joy of colour. Take Mr. Whistler’s ‘Symphony in White,’ which you no doubt have imagined to be something quite bizarre. It is nothing of the sort. Think of a cool grey sky flecked here and there with white clouds, a grey ocean and three wonderfully beautiful figures robed in white, leaning over the water and dropping white flowers from their fingers. Here is no extensive intellectual scheme to trouble you, and no metaphysics of which we have had quite enough in art. But if the simple and unaided colour strike the right keynote, the whole conception is made clear. I regard Mr. Whistler’s famous Peacock Room as the finest thing in colour and art decoration which the world has known since Correggio painted that wonderful room in Italy where the little children are dancing on the walls. Mr. Whistler finished another room just before I came away – a breakfast room in blue and yellow. The ceiling was a light blue, the cabinet-work and the furniture were of a yellow wood, the curtains at the windows were white and worked in yellow, and when the table was set for breakfast with dainty blue china nothing can be conceived at once so simple and so joyous.”

At the same time, he wanted each house to be individual to the owner. According to Deborah van der Plaat in her article “Cosmopolitan Interiors: Oscar Wilde and the House Beautiful,“ “Wilde explained and give detailed directions to the attendees as to how to set up the Aesthetic home: Starting with the entry hall, which should have a red tile floor, a hat rack and no pictures or stuffed animals under glass cases, Wilde then outlined the appropriate colour according to room type (“The problem with America,” he concluded, “is the entire want of harmony or a definite scheme in colour”); the style of furniture to be used (Queen Anne); the treatment of ceilings (papered or painted); floor coverings (carpet squares, preferably from China, Persia and Japan); window size and colour (to avoid glare); lighting (a gas chandelier will “discolour and ruin all that you do”); the hanging of pictures (never in a row); the treatment of paintings (photographs are “libels on great masters”); the arrangement of flowers (never arti ficial or crowded together); the ornamentation of the mantle (with shelves to the ceiling for rare china ornaments); and the importance of old Japanese or Blue and White china . Suggesting the inclusion of “some good casts of old Greek work” and books (“an old library is one of the most beautifully colored things imaginable”), he concluded his commentary with the observation that “beautiful surroundings” should not be “marred” by “gloomy dress..”

A Typical Victorian Interior by Knut Ekwal in the painting The Proposal

The Aesthetic Movement, of which Oscar Wilde was a part, was a broad social phenomenon that activated nineteenth century clothing, for both men and women, a simple and clean style of furnishings, and a position that regarded redesigning the “home” and the people in it as a work of art. As Walter Crane advocated, if one were educated in the arts, and what was meant by “education” was art history and a lesson in “taste,” then one, anyone, can be a decorator. Van der Plaat also quoted Wilde himself on the subject of women as home decorators: “It has been from the desire of women to beautify their households that decorative art has always received its impulse and encouragement. Women have natural instincts, which men usually acquire only after special training and study, and it may be the mission of the women of this country to revive decorative art into honest, healthy life.” Wilde did not confine himself to the interior of the home. “House Beautiful” should also be applied to the exterior. Americans, unlike Europeans, had the unique opportunity to hire their own architect and build their own houses and, hence, creating a unique or “individual” house to order. But the new homeowner needed to be a reformer of obsolete Victorian taste. As Van der Plaat said,

Wilde spent a significant portion of his lecture time dealing with the preferred materials, colours and ornamentation of the urban façade. As with his consideration of the interior, his suggestions are often straightforward and practical. First, he dealt with materials and described the appropriate and best use of marble, stone, wood and brick. If marble is to be used, it should not be treated like ordinary stone as a “mere building block,’ a practice that produces “great, plain and staring white structures.” Instead, he said “I hope you will employ workmen competent to beautify it with delicate tracings and that you will have it beautifully in-laid with colour marbles, as at Venice, to lend it colour and warmth.” Turning to the use of stone, Wilde encouraged his audience to take advantage of the “natural hues’” that could be found in America, ‘from pale yellow to purples, red to orange, [and] green to grey and white.’ ‘Ingraining them’ would produce “beautiful harmonies.” When marble or coloured stones were unavailable, there remained the option of red brick or wood. Wilde identified wood as a ‘universal material’ and discouraged Americans from painting their houses white or grey: both ‘are dreary in wet weather and glaring in fine.” Rather, warmer colours, “the rich browns and olive greens found in nature,” should be used. In a manner reminiscent of the stone or marble house, enriched with ingraining and carved tracery, the wooden house should also be made ‘more joyous to look upon with the aid of the carver. “Red brick, which is warm and delightful to look at, and a simple form for those who do not have too much to spend,” was the fourth material considered. An advantage of the cut brick, Wilde observed, is that it “gives you the opportunity of working in terra cotta ornamentation, the most beautiful of all exterior decorations – the old Lombard’s special pride, and an art we are trying to revive in England.” He strongly suggested that all exterior ornament should be ‘carved’ and not cast or machine-made and concluded his discussion of the exterior with the proposition that the common use of the ‘black-lead [door] knocker should give way to a bright brass one.”