The Traveler, the Logo, and the Wardrobe

We all pack, wrestling with tiny cases, usually with long handles and wheels, stuffing clothes, cosmetics, and computers into a designated number of inches that can fit between the seats of an airplane aisle, jam into an overhead bin, or roll under our narrow seat. Decisions must be made–a change of clothes or something to sleep in, a pair comfortable shoes or rain gear–depending on the climate or circumstances, but more often than not we will leave something behind or realize–too late–the wrong choice was made. Our twenty-first-century angst is largely misplaced. If we forget an item, we can easily go to a store and replace it. In fact, if we were sensible, we could board a plane with a nice tote bag and shop upon arrival, but we are in the habit of traveling with our own possessions and we plan our itineraries around our outfits and it is not for nothing that the first “carry-on” bag was called a “suit case,” or a case for a suit. What we would not give for a Louis Vuitton (1821 – 1892) in our lives, our very own layetier, a professional packer. Photographs show a rather scowling visage but Vuitton had no reason to be so somber. He turned his knowledge of packing a box full of clothing into an international enterprise that would symbolize luxury.

In today’s do-it-yourself world, the idea of servants is a guilty pleasure played out on Downton Abbey. It is always a surprise to hear of specialized servants who do one thing very well, but Vuitton had learned the fine art of traveling with an appropriate selection of one’s clothes, which meant that packing a container was a specialized craft. One of the remarkable facts about Vuitton, the inevitable beginning in every retelling of the origin story, is his three-year walk from the village of Anchay in the Jura region to Paris. He left his family in the rural region and must have felt so strongly about not being a farmer that he was willing to invest in his faith that something better must be waiting for him in the city. His biographer, Fergus Mason, who wrote, Vuitton: A Biography of Louis Vuitton, that his mother was a hat maker, a milliner, who supplemented the family income by making and selling hats for the surrounding countryside. Mason noted that the village of Anchay is still as off the beaten path now as it was almost two hundred years ago. We can assume that the three years were not years of steady walking but a journey interrupted by brief jobs which gave him food and shelter and enough money to continue down the lanes to his destination. We can imagine that his months and years of being on the road gave him a knowledge of packing efficiently–indeed, Vuitton must have grown from an adolescent to a young man during these years–for any weather and any occasion. How else can one explain how a country boy who may have been a jack of all trades was taken on as an apprentice Layetier-Malletier, according to Sidonie Sawyer, by Monsieur Maréchal in 1837.

As Sawyer pointed out in “Louis Vuitton, the Original Box-Maker,” “In those days, box-making and packing was a highly respectable craft, as the maker and packer had to specially make all the boxes to fit the goods they stored and personally loaded and unloaded the boxes in clients’ carriages. It took Vuitton only a few years to master his craft.” This vocation had probably existed for hundreds of years and in fact, “The word “layetier” appears around 1582, from its origin “laie” laot, small chest of the Middle Age where are kept jewels, documents, items of value, and clothes..” In her 2004 book Louis Vuitton: Un saga française, Stéphanie Bonvinci, wrote of the origin of specialized boxes used for traveling. The original box seems to have been small and specialized but undoubtedly there were always large boxes used for transporting personal goods and we can assume that ordinary people did not have either jewels or documents of anything of value, much less an assortment of clothes. From the start, therefore, the ancestor of the nineteenth-century trunk was a luxury item used by the wealthy, the powerful and the important. Centuries later, Monsieur Maréchal undoubtedly had the same clientele–the rich and the important–and it is clear that such containers were made to order, specialized for certain contents and sized according to the capacity of the vehicles used in the conveyance from one site to another. In the 1830s, the number of people in private or public life who needed such services would have been limited and the name of “Louis Vuitton” as an excellent packer could have easily come to the attention of the Emperor Louis Napoléon.

Two silk day dresses (1850)

Emperor Napoléon III had a wife, Empress Eugénie, who was a leader in fashion. By 1852 when Vuitton was appointed Layetier to the Empress, the gowns for the elite women were, for lack of a better word, voluminous, of delicate materials, and could not be crushed or folded. Although Charles Worth had made his mark in 1851 in the Great Exhibition in London and would not open his enterprise in Paris until 1858, the Metropolitan Museum of Art owns two lovely silk day dresses dated 1850 with full skirts and puffed sleeves, delicate collars, and fabric folded like a shawl over the bodice. Later, hoops and crinolines would be added to the outfit to expand the skirt, making the wearer bloom and blossom like a large moving flower. The famous 1855 portrait of the Empress and her court of ladies, Portrait of Empress Eugénie Surrounded by Her Maids of Honor, demonstrated the most fashionable look of the era, courtesy of Charles Worth. One can only imagine the skill of a Louis Vuitton in the fashioning of boxes to enfold without crushing the many outfits of an Empress on the move from estate to estate. In fact in 1854 only a few years after he had become the official packer to the most important woman in France, Vuitton opened his own firm at 4 rue Neuve-des-Capucines as an important Layetier-Malletier. The sign outside his shop read, “Securely packs the most fragile objects. Specialising in packing fashions,” thanks to the recommendation of Charles Worth, who liked how Vuitton packed his garments.

A year earlier an even more exclusive Layetier-Malletier, re-named Goyard, took over Maison Martin, founded in 1792 by Pierre-François Martin. When François Goyard purchased the business it was called Maison Morel. True, Bally was founded even earlier in 1851. According to the story of this long established firm, Martin was box maker to Duchess de Berry. In fact, by the late eighteenth century, box making and trunk making and packing the containers was a well-known profession. If anything, the hats and dresses of that century were even more complicated than those of fifty years later, and this firm also manufactured fabrics that were waterproof, that is, canvas, both oiled and plain. In the nineteenth century, both Goyard and Vuitton would design logos for the fabrics that covered their trunks and in another odd coincidence, Goyard moved his shop at 4 rue Neuve-des-Capucines to 233, rue Saint-Honoré in 1854. According to Bonvinci, a specialty fabric, the“goyardine” canvas” was created in 1872. Twenty years later Edmond Goyard, the successor to his father, took the Y in the name and turned it into a chevron design that was handpainted in a series of dots on the canvas.

The precise history of this family and the business seems to be in the possession of the official account of the firm itself and the dates and details vary. For example, Goyard described the fabric and the logo as if they were invented at the same time: “When Edmond Goyard created the Goyardine canvas in 1892, he was inspired by his family history: the piled up dot pattern clearly hints at logs driven by his ancestors, and, although its appearance is similar to leather, the Goyardine is made with the same natural coated cloth mixing linen and cotton that the Compagnons de Rivières used for their garments. At once hard-wearing, soft and waterproof, the Goyardine proved a true technical revolution at a time when other trunk-makers were using plain linen cloth. Like all family secrets, the exact manufacturing process of the Goyardine remains strictly confidential. Though it was originally hand-painted, the current process requires a ground-color application, followed by three successive layers of etching colors that create its trademark slightly raised pattern.”

The idea of a logo was a fairly new one and undoubtedly helped to brand the elite Goyard goods. In fact, the year of the origin of this distinctive design, 1892, was also the heart of the Gilded Age. In the novel What a Lady Wants: A Novel of Marshall Field and the Gilded Age, Renée Rosen wrote in 2014, “The day after their visit to the House of Worth Delia and Abby visited several boutiques along Saint-Honoré. There they purchased dozens of handkerchiefs from one shop and fans and hair combs from another. The following day she and Abby shopped for their bloomers and corsets before ending up at Louis Vuitton on rue Neuve des Capucines. By the end of the week, after their fittings and alterations at Worth, Delia realized they were never going to get everything home in their luggage. So they went to Goyard’s at the corner of rue Saint-Honore and rue de Castiglione, where they purchased half a dozen steamer trunks. While they were there, Delia made arrangments for Edmond Goyard himself to pack their new wardrobe after Worth finished with their gowns. Four an a half weeks later when they returned to Chicago, Delia found her new dresses handing in her closet looking every bit as perfect as they had when Worth presented them..”

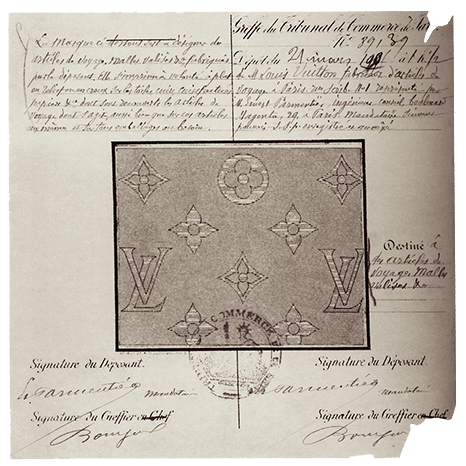

Damier Canvas with registered Trademark for Louis Vuitton These tiny dots had a story of their own. Like Vuitton, the origins of the Goyard family were rural and humble, and, like Vuitton, the story of this family also involves traveling and transportation. The name “Goyard” is derived from a tool that was used to remove thorns or small branches from stakes or logs. The business of the family was to transport logs cut to firewood size from the countryside to the city of Paris. The log moving business probably dated from the early 17th century when a physician in Paris, a doctor with a scientific mind, Louis Savot, realized that a fireplace–a special place for an indoor fire–could be built with three sides which funneled the smoke upward and allowed the heat to enter the room from the opening. Savot built the first modern fireplace in the Palace of the Louvre itself. It was here in the interior of the fireplace that the logs would be placed and burned. The story of the Vuitton logo begins a few years later. In Luxury China: Market Opportunities and Potential, Michel Chevalier, Pierre Xiao Lu wrote “In 1888, he produced his first classic signature pattern damier, a checkerboard print of light and dark contrasting brown squares. From the damier, came his most identifiable and popular selling canvas Monogram in 1896.” It was Georges Vuitton (1857 – 1936) who created this famous logo described, in another official source, as “in tribute to his father, Georges Vuitton creates a canvas design with alternating LV initials, diamond spikes, stars and four-lobed flowers. The monogram canvas patent is registered in 1905.” It is clear that the two box makers knew each other and the two firms have co-existed peacefully ever since, although the name of Louis Vuitton is far more well known. What distinguished Louis Vuitton was his reinvention of the trunk itself. As the accounts of wealthy travelers attest, the women (and probably the men) traveled with multiple trunks. For a very long time, these trunks had been designed with circular lids, raised to a slight incline, like a speed bump of today. This dome was convenient when it rained as the water could flow off the top, but the shape was very inconvenient, necessitating placing the various trunks side by side. Interestingly, the meticulously packed trunks resisted efficient packing themselves. The reason for the domed lid was the fact that the wooden boxes were covered in leather which could resist water but could not tolerate it but for a short time. Vuitton traded this porous leather for a sturdy waterproof canvas and a well-made wooden trunk with a flat top that could withstand a waterfall of rain, thanks to waterproof fabric. To make sure that water did not penetrate the boxes, Vuitton covered the wood with gray Trianon, a waterproof canvas, his first attempt at creating a trademark “look” for his now distinctive trunks. But by the mid-1850s, the design had become so renowned that Vuitton took steps to thwart copies with a new canvas that was beige with brown stripes, then he created the Damier Canvas which had an early version of the logo: “marque L. Vuitton deposée.” And now his flat-topped trunks could be stacked, one on top of the other. Given the large size of the trunks used for dresses–the size of small wardrobes–layering the traveling containers in a pyramid saved space. The Trianon gray trunk is shown below Fergus Mason pointed out that Vuitton was a keen observer of what people who traveled needed and their needs changed in an increasingly industrial world of trains and ships that were comfortable if not luxurious enough to allow the wealthy to travel more frequently and for pleasure. Europeans preferred trunks to the heavy suitcases, toted by the stalwart English. Louis Vuitton and his designs won a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle in 1867, but he was beaten by a London firm, H. L. Cave. But he also won a gold medal for the high-quality Damier fabric and for his idea of patenting a design. Finally, he won a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1889. In between, France had lost a war with the rising nation-state, Prussia. The city of Paris was invaded and occupied by soldiers who looted when they could, including Vuitton’s workshop, which was destroyed. Vuitton moved from rue neuve des Capucines to the rue Saint-Honoré where one of the Parisian stores is located today. The main workshop has been and is still in Asnières-sur-Seine, on the banks of the river for easy shipping of the products from the suburb to Paris by a Louis Vuitton barge. Asnières is perhaps best known as the site of one of Georges Seurat’s best-known paintings, the Bathers at Asnières (1884). It is interesting to think that if Seurat had shifted his gaze a bit, he might have included the Vuitton workshops. The trunks handmade by craftspersons were almost always custom made for the individual customer and crafted as a result of consultation about the needs of the client. It is to be assumed that one of those interviewed by the trunk maker would be the lady’s maid or the gentlemen’s valet, who after all, did the packing and unpacking. The round hatboxes for women’s hats were supposedly sized for the well of the spare tire of an automobile and could, therefore, be taken on short journeys. For long trips on a train or a “steamer” or an ocean liner, an assemblage of trunks could be gathered together for the voyage. Men and women of a certain class were expected to dress for dinner and the ladies would be decked out in their finest jewelry. For the elegant travel at the turn of the century and well into the 1930s, trunks had to be designed to hold personal toiletries, jewelry, guns, dresses and matching shoes, top hats and boots, because there could be no shopping on trains or ships. This assortment of luggage would be kept on baggage cars or in baggage holds in a ship, meaning that the contents of haute couture clothing and bespoke tailoring would tempt thieves. Louis Vuitton was very aware of the need to protect the contents with a lock that could not be broken into. An article on the famous Vuitton lock stated, “The founder was attached to changing all of the less practical aspects of luggage in those days. First came the shape of the trunks, then the issue of security. Louis concentrated on a project: helping the closing system of trunks evolve to make them impenetrable and inimitable. He worked with different types of locks, going from one supplier to the next, always seeking a more ingenious system and the best way to counter the new problems of the era. In 1896, after years of research, he arrived at a breakthrough… In an era where travelers transported all of their personal effects in wardrobes and trunks that would attract envy and, unfortunately, thieves as well, this trunkmaker dared to create the only lock that was supposedly unpickable. This was no accident. The creation of the unpickable lock is due to a subtle balance of tradition and innovation, enlightened dreams and down-to-earth pragmatism. With one lone key for one lone bag, the public still had to be convinced of the truthfulness of Louis Vuitton’s claims. Georges, his son, would take on Harry Houdini: the dare was to get out of a box closed with a Louis Vuitton lock. With an onlooking crowd, Houdini wasn’t able to escape, and the lock’s efficiency was proved. The trunkmaker thus issued a response to the new demands of the day. The cover’s lock was ensured through a three-point system that would secure the trunk. Numbered and stocked, the keys were linked to the individual client who would receive a unique lock number. Today, of course, Louis Vuitton produces more bags than trunks, but the lock is still the brand’s signature. Since 1901, it’s adorned every bag as well.” This account has been challenged by Fergus Mason who said that Houdini never accepted the challenge, and this bit of fact has been cited by other authors as well For a more adventurous traveler, far away from the comforts of a stateroom, there was the bed-trunk for a sleeping on a safari. The bed-in-trunk can be seen in 1888 in the courtyard of the Asnières workshops. The group photograph shows the patriarch, Louis, with next generation, Georges, who would invent the famous LV monogram to prevent copying of the fabric. The child stretched out on the unfolded bed is young Gaston L. Vuitton at the base of a delivery cart. Gaston, the third generation took over the firm in 1936. He also collected the older models of the Vuitton custom-made trunks, starting the foundation of the museum collection housed in Asnières. According to one of the official websites for Louis Vuitton, many explorers of the fin-de-siècle were patrons of the firm. “In

1868 the bed-trunk were ordered by the military officers for campaigns and exploratory trips. And 1905 the bed-trunk used by Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza. This French explorer of Italian origin remains linked to Congo. After a first exploratory mission from 1875 to 1878. During his second mission 1880-1882, the diplomat to sign a peace treaty with Makoko Batéké (thought of as the king of Congo in France). For his third mission in 1905, Pierre de Brazza Savorgnan is appointed by the Minister of Colonies to investigate abuses committed against Congolese. Before his departure, he commissioned a series of trunks, of which two were bed-trunks, each adapted to his size.” (corrected translation) A decade or two later, it was Georges who promoted the idea of a luggage rack for the back or top of an automobile, where the luggage could be stacked. The assortment below includes a trunk two suit cases, a hat box and two specialized containers. Cars for the wealthy were long and low and could accommodate such a load of prestigious luggage. The son and heir of Louis Vuitton, Georges, took the company to the twentieth century. A decade or two after the age of exploration, it was Georges who promoted the idea of a luggage rack for the back or top of an automobile, where the luggage could be stacked. And it was Georges who designed the famous LV monogram that became the motif of the signature fabric that covered the trunks. On one of the many company oriented websites, his son explained the design of the logo: “First of all, the initials of the company – LV – are interlaced in such a way as to remain perfectly legible. Then a diamond. To give a specific character to the shape, he made the sides concave with a four-petal flower in the centre. Then the extension of this flower in a positive image. Finally, a circle containing a flower with four rounded petals.” For the past few years, Louis Vuitton, the business, the brand and its many speciality items of luxury have moved into the realm of art, deemed worthy of museum exhibitions. On one hand, such exhibitions blur the line between art and commerce but on the other hand, the idea of a trunk as a work of art is the entry of a timeless design being respected on the level of art and of craft being considered an accomplishment suited for history. But, as was seen in Moscow in 2013, the manifestation of commerce in the service of art can cross boundaries of good taste and judgment. In November of 2013 Gabrielle Tetrault-Farber wrote of the “Shameful” trunk in Red Square. The offending trunk was an enormous replica of Louis Vuitton luggage on a plinth, an unwelcome object injected into a World Heritage site, its bulk obscuring the iconic buildings of Red Square. According to Tetrault-Farber, Outrage from all echelons of Russian society began as workers completed the installation on Red Square on Tuesday. By Wednesday afternoon, workers had already begun dismantling the structure, which was set to host a six-week exhibition of Louis Vuitton’s luggage..The move comes after several Communist deputies criticized the Kremlin for allowing the suitcase — which is nine meters tall and 30 meters long — to be set up on Red Square. “This is a sacred place for the Russian state,” said Sergei Obukhov, a member of the Communist Party Central Committee, RIA Novosti reported. “There are some symbols that cannot be trivialized or denigrated.”..The installation, which blocks the view of the Spasskaya Tower, the Kremlin walls and Saint Basil’s Cathedral from certain angles, was intended to honor the 120th anniversary of the GUM department store, located across from the Kremlin, with the “Soul of Travel” exhibition..Both the Kremlin and opposition parties, factions that rarely agree on anything, are united by their disgust with the infamous suitcase. But the opposition has nonetheless tried to capitalize on the Kremlin’s apparent mishap, which allowed a French corporation to occupy Red Square with a blown-up version of a luxury item that the average Russian cannot afford. The Trains section of the Paris Exhibition 2015 Two years later in 2017, the company had better luck in Paris with the “Volez, Voguez, Voyagez” exhibition of the firm’s most iconic designs and custom trunks. In the Palais Galliera, the fashion museum of Paris, six hundred of the company’s twenty-three thousand objects were on view. In writing for Forbes about the “star” of the exhibition, the trunk, Y-Jean Mun-Delsalle, reported on the craft of box making, saying that “their manufacture that reproduces the same gestures as 162 years ago: a bespoke wood structure and the application of cement, canvas, lozine, malletage and metal corners and screws. Just like carpentry, they involve cutting, fitting, splitting, sharpening and assembling, with poplar used for the barrel, beech for the reinforcement strips, camphor wood for the interior to keep pests away and rosewood for its pleasing fragrance. These protective cases were designed with care to perfectly envelop the contours of their precious contents like a glove with the aim of ensuring the safest journeys, perfectly thought out just for the traveler’s items that they were made to hold.” In fact, the Louis Vuitton exhibition was about the work of a father and son team who followed the advances in travel and adapted the necessary containers for the clients, following them on their journeys. As the author noted, “the brand closely accompanied all the new modes of transportation: cruise ships, trains, cars and planes. Steamships went into operation in 1830, the railways in 1848, the automobile in the 1890s and commercial airlines in the 1900s.” It could be asserted that by the beginning of the twentieth century, the Louis Vuitton line achieved its final form. Although today, the trunks might be specialized for chef’s knives rather than the huge ball gowns of a French Empress, the basic design developed by Vuitton set a paradigm and almost two hundred years later remains on of the few objects that have come through time as is–no modifications necessary. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.