Deliberate Destruction

The Unblinking Eye of Richard Misrach

There is the technological history of color photography and then there is the social history of color photography and finally, last but not least, is the art world acceptance of color photography. If one wants an excellent tutelage on the slow and multifaceted discussion on the slow conversion from black and white to color, look no further than Annette Roulier’s 2008 A Short History and Concepts of Color Photography, which is not only illustrated but also to the point–technologically speaking that is. The point that this guide makes is that color was sought for photography ever since its invention but proved to be elusive for over a century. Once color arrived, it was eagerly taken up by advertisers for magazines, which seemed to be the ideal resting place for the garish and unreal colors, more suited to cartoons and other regions of the unreal. Artists scorned the artificial excesses of such exuberant coloring, seemingly disgraced forever by its connection to commercialism. When viewed in perspective, the scorn for color coincided with the last gasp of black and white movies in America and Europe. From the Nouvelle Vague–think Last Year at Marienbad—to Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, the elegant chic of black and white with shades of gray, had its final years, fighting it out with color films which, by the 1970s, were increasingly dominant. Parallel to the trend towards color was the booming sales in color television. In comparison, the acceptance for color photography lagged behind, held back, as with all things in the art world, by snobbism.

Robert Frank who had set the postwar aesthetic standards declared that “black and white are the colors of photography” and Walker Evans thought that color photography was vulgar. The ideology that only black and white photography was suited for the art world reflected the split between high–art–and low–popular culture–that cut visual culture in half, cleaving fine artists from commercial artists, serious painters from illustrators, and so on. In other words, as American art came to define “art” after the Second World War and as the center of the art world migrated to New York, strict rules and regulations that came to characterize this era manifested themselves to buttress the sudden seriousness of a once-provincial art scene. However, as fast as norms were set up, challenges were thrown up in the guise of Pop Art, where bright advertising colors jarred the souls of admirers of Abstract Expression. That said, it was not until the end of the seventies, in the midst of Conceptual Art, that color photography finally walked through the doors of a museum. The decision on the part of John Szarkowski in 1976 to mount a show modestly named Photographs by William Eggleston at the Museum of Modern Art, the arbiter of “art,” was an announcement that color photography had arrived. But there is a subtle difference: Eggleston’s work was accepted but not as “color photography” but as the use of color in photography, in other words, an “art” like manipulation of color with photographic film. Eggleston used dye transfer, a complicated printing technique, as opposed to the ordinary color of commercial film to produce a saturated image, thick with hues that vibrate in intensity. Like Evans and Frank, William Eggleston (1939-) photographed the vernacular landscape. The older photographers had used black and white to make serious their non-serious subjects, and Eggleston used vibrating colors to reduce his quotidian images to relations among colors.

William Eggleston. Untitled from The Democratic Forest (1983-1986)

It is really Stephen Shore (1947-) who deserves more credit than he usually gets for pioneering color photography as early as 1972 and in an exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1972. The Met lacked the clout of Szarkowski and MoMA to change hearts and minds. The reception was hostile because the Shore’s pale-hued photographs of ordinariness exceeded the horizon of expectations. The images and their subtle color relationships could not be seen outside of the pre-existing confines of advertising. Speaking to The Guardian, Shore later remembered that “People just did not exhibit colour images then. I remember the great Paul Strand taking me aside and advising me in no uncertain terms that it would be a disastrous career move. I am often asked what it was that people objected to exactly in the show and the answer is: all of it. Everything.’’

Stephen Shore. Broad Street, Regina, Saskatchewan, 17 August, 1974 (1974)

Today we realize with hindsight that it would be Shore’s naturalistic use of color photography as opposed to Eggleston’s exaggerated and stylized images that led to the present day when to make a black and white image is to make a statement as strong as that of Eggleston in 1976. Color photography quickly became the norm during the 1970s and 1980s with a younger generation of artists. Some of these artists such as Eliot Porter and Joel Sternfeld, along with Stephen Shore, used color photography in a direct and straightforward manner–to show the world as it is in all of its American beauty. Still following in the footsteps of Frank and Friedlander, Shore and Sternfeld, sought the remarkable hiding in pain slight in the midst of everyday life. Color enhanced the amusing story of an escaped elephant captured on a remote highway, just as color brought an ordinary street corner to life. But there were other photographers who found color photography a path to a new form of conceptual art that began emerging by the 1980s. Like Peter Goin, Richard Misrach (1949-) took up the camera and inserted rolls of color film to make political statements about the world as it is in all of its American ugliness.

Richard Misrach. Telegraph 3 A.M.: The Street People of Telegraph Avenue, Berkeley

Photographers, with the possible exception of portrait photographers, are travelers. Some, like John Thomson, were adventurers, seeking new-found lands, others, like Walker Evans a man of the northeast treated the southeast as if it were a foreign nation. Ansel Adams devoted his life to revealing the marvels of the American West. Somewhere between Adams and Misrach the idealism that drove the founding member of f64 dissolved, perhaps evaporated by nuclear testing and Cold War extremism. Cynicism became the prevailing attitude of the Postmodern Age, and a period of prolonged mourning for the optimism of modernism began in the 1980s. Following in the footsteps of no previous photographer, Misrach wandered the American landscape, seeking its wounds. An early work, Telegraph 3 a.m. The Street people (1974), featuring Telegraph Avenue in Berkely, is in black and white, and some twenty years after The Americans (1958), the series seems outdated. Nevertheless, in 1973 when it was awarded an NEA grant and a Western book award in 1974, the positive reception of this post student work suggested that the Robert Frank street photography tradition was still potent. It with the Desert Cantos series, begun in 1981 and concluded in 2001, that Misrach found his authentic voice. The catalog essay, “The Man Mauled Desert,” was written by Reyner Banham who remarked, “One of the reasons that the proposition ‘the desert is where God is and man is not’ does not mean much to me is that, puzzled to know what I am doing in the desert, I hope to find illumination of what other men have been doing in the desert, why they did it, and why they thought it proper to do so. And there may be a bigger issue here than the identifiable activities of particular individuals and organisations. I begin to wonder what men have to do with the very existence and continuance of deserts; and if their presence is not more vital to deserts than that of the various gods that men have brought in with them.”

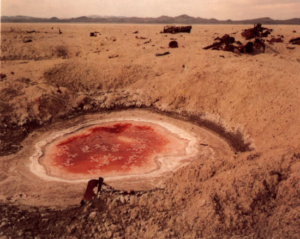

Richard Misrach. From Desert Cantos (1984)

As a photographer of wastelandsRichard MIsrach was in the company of Peter Goin and John Pfhal, finding sites that had been deliberately destroyed by forces divorced from nature and from the people and animals who were left to grappled with the ruin left behind. A canto, a term applied (ironically) by Misrach to his series of photographs in the West, comes from poetry, found in very long poems and functioning like chapters in a book. The early use of cantos can be found in the poetry of Dante Alighieri’s Commedia (The Divine Comedy) from the early fourteenth century. The First Canto begins with the poet being lost in a forest, searching, much in the way that Misrach made his way through the West.

Midway upon the journey of our life I found myself within a forest dark, For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

Ah me! how hard a thing it is to say What was this forest savage, rough, and stern, Which in the very thought renews the fear.

So bitter is it, death is little more; But of the good to treat, which there I found, Speak will I of the other things I saw there.

Divine Comedy, divided into three books or canticles, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso, each with thirty-three cantos. The Comedy was written between 1302 and 1314, while Dante was in exile from Florence. The meandering poem and the author’s meditations on the nature of religion and faith spoke of Dante’s lack of place and peace of mind during turbulent times. This search for the truth, guided by the ancient poet Virgil, can be read as a political allegory and Dante’s commentary on his own time. What made the Comedy remarkable in its time lies in the title, “comedy,” meaning commonplace literature, compared to high minded writing such as tragedy. In addition, Dante’s epic was conversely written in the vernacular language of Tuscany. The first English poet who took up Dante’s form of writing was Edmund Spenser in The Faerie Queene (1590) written in a difficult form of early English, created a dream-like world, drawing upon myths and legends from British pre-Christian stories. The total poem totaled over 1200 pages but was never finished. Political in intent. like Dante’s Comedy, Spencer’s “Queene” was Elizabeth in the midst of religious quarrels, as Rome, the Catholic Church, grappled with a new Protestant monarch on the English throne. Spencer thought that poetry, a more vernacular communication, would be more convincing that dry philosophical tomes, but one would have to be conversant with Tudor controversies to properly interpret The Faerie Queene.

Upon a great adventure he was bond,That greatest Gloriana to him gave,That greatest Glorious Queene of Faerie lond,To winne him worship, and her grace to have,Which of all earthly things he most did crave;And ever as he rode, his hart did earneTo prove his puissance in battell braveUpon his foe, and his new force to learne;Upon his foe, a Dragon horrible and stearne.

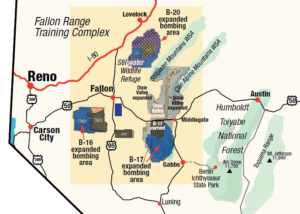

Richard Misrach found it convenient to divide his long study of the ravages done to the West into cantos, suggesting that his photographic odyssey is a kind of extended mourning as he enters into what seems to be pits of hell on earth. As Spencer’s moral theme was the contrast between Concord and Discord, Misrach’s Cantos are equally moral. Published as an (unfinished) project in 1987, Desert Cantos was followed three years later by Bravo 20: The Bombing of the American West. In 1980, in a “Final Environment Assessment for Withdrawal of Bravo-20 Bombing Range, Naval Air Station, Fallon, Churchill County, Nevada” the Navy stated that this bombing range was “Located on the sand dunes at Lone Rock is a biological community surrounded by the sterile alkali playa. Based on a field survey of the area, no rare or threatened species are known or expected in the sand dune community..” Then a few paragraphs later, the report considers the fact that abandoning the area would necessitate expensive decontamination, costing $323,921,000. Not only would the cost of cleaning contaminates be staggering, “Decontamination would potentially impact archaeological resources if present and would disrupt the biological community on the sand dunes around Lone Rock.”

Richard Misrach. From Bravo 20. Fallon, Nevada (1986)

Belatedly, the report defined Bravo-20 as “an unmanned weapons range that has been operating since the early 1940s This range is described as a high impact facility and is used on a daily basis by both single aircraft and squadrons. Between 580 and 710 aircraft in an average month use BRAVO-20. In addition to its use by aircraft from NAS Fallon, the Range is also used for scheduled bombing practice and jettisoning of unsafe ordnance by neighboring stations.” This site, according to the report, had many virtues, “Because of its relative remoteness from developed and inhabited lands, BRAVO-20 is used for a type of air strike exercise that is not practiced elsewhere in the United States.” The report makes it clear that the costs of the Navy withdrawing from this site went beyond the hundreds of millions required for decontamination. Naval personnel would also be impacted. “Elimination of BRAVO-20 Range could significantly limit the training of pilots in bombing, gunner, and air strike exercises.” However, the report admits. “Elimination of the air-to-ground weapons delivery training from BRAVO-20 would provide some benefits to public safety in that the dropping of live ordnance and other hazardous materials would cease at the Range.”

Richard Misrach. From Bravo 20. Fallon, Nevada (1986)

In the midst of the lands concerning this official report, written in 1980, was Richard Misrach, who took advantage of the 1872 General Mining Law that allowed him to enter into this very testing range. As Mark Squillace explained in his article “The Enduring Vitality of the General Mining Law of 1872,” “.. the initial question confronting the mineral prospector is whether the land on which he is prospecting is open to location under the mining laws. If the lands are open, the prospector may proceed directly onto the public lands and carry out all necessary prospecting activities. Prior approval generally need not be obtained. Furthermore, so long as the prospector remains on the land diligently prospecting for minerals, he has some protection against all later claimants.” Misrach could claim the land so to speak as long as he worked his claim, an activity interpreted by the photographer as doing what he did best—photographing the area for evidence of Naval bombings as a miner would search for gold. What he found was dross. Misrach could have chosen, like Adams, protected national parks, relatively pristine and untouched, but he took a more dangerous path and entered into a land that had been misused in the name of public good. He explained, “I began the Desert Cantos project around 1979. For over a decade, I have been searching the deserts of the American West for images that suggest the collision between “civilization” and nature.”

Richard Misrach.

Over time, the photographer began to realize that “landscape” as a genre had become politicized. Perhaps one can place the starting point as the New Topographics movement, but to go from a critique of development in the American West to the bombing of the West. Misrach noted the gradual realization that at some point, his work shifted from being a mere representation of terrain to a revelation of something darker, perhaps an environmental crime. He said in an interview for aperture in 2015, “Victor Burgin underscored a significant point when he made the distinction between the ‘representation of politics’ and the ‘politics of representation.’ Nonetheless, despite the limitations and problems inherent to photographic representation (and especially the representation of politics), it remains for me the most powerful and engaging medium today—one central to the development of cultural dialogue. The Desert Cantos project of the last decade has shifted somewhat in the nature of its representation..Recent cantos, however, have become more explicitly political. The “Bravo 20” project points a finger directly at military abuse of the environment.”

In 2016, the Navy proposed to requisition this land once again,

withdrawing it from public use in order to return to military exercises.