Killing Fields

And Acceptable Risks

Who knows what the High Museum was thinking when it asked famed photographer Richard Misrach (1949-) to produce a series of photographs for their ongoing project, “Picturing the South.” By 1998, Misrach was known for his environmental and political bodies of work, so his decision to document one of the most dangerous and polluted sites in America that just happened to be in the South, a place called “Cancer Alley,” could hardly be complementary to the South. His study would mark the great distance between himself, a political actor, and William Eggleston, who chronicled the vernacular “Pop” life of the South. The vivid colors of Eggleston brought to life the details of the region, from drive-ins to Confederate flags, without comment. The apparent lack of critique in Eggleston’s work is not only characteristic for the late 1970s, it is, most importantly, the result of a long-time resident of the South. Eggleston merely records what he sees, what he knows. In contrast, Richard Misrach, a native Californian and a long time explorer of the West, came to the South as a stranger in a strange land. In many ways, he was a latter-day Robert Frank, coming to America from Switzerland. Whether or not Frank deliberately exposed or merely revealed the political and social divides in the nation during the mid-1950s can be debated, but Misrach had always been a sharp-eyed and remorseless observer of human conduct and its impact on the environment. He arrived in the South almost three decades after the Environmental Protection Act was passed in 1970 to find that the topic of his series on the Mississippi River would be pollution.

In explaining the circumstances of selecting a stretch of river so polluted and so dangerous for those within in range of wind-borne pollution and toxic spills that the population had such an abnormally high rate of cancer that the narrow banks of the River were called “Cancer Alley,” Misrach recalled, “I made the original trip in 1998 on a commission from the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. It was a series called “Picturing the South.” I set out with no expectation of what I was going to do, no restrictions from the museum. I had some ideas about photographing Ku Klux Klan sites or doing Civil War battlegrounds. I decided to fly to New York, rent a car, and then drive south, just wander around. I explored and took all kinds of reconnaissance pictures of potential ideas. At some point, somebody turned me on to the River Road in Louisiana, and the industrial corridor that was then called “Cancer Alley.” When I got there, I was just floored by what I saw. I had never come across an American landscape like that.”

For years Misrach photographed the eighty miles long journey taken by the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge. He followed in the footsteps of Mark Twain who wrote of this stretch of the Mississippi in 1876, one hundred and twenty years before Misrach began his own trek. Even in 1876, this part of the Mississippi was already environmentally fragile. Twain wrote in Life on the Mississippi, “..from Baton Rouge to New Orleans..The river is more than a mile wide, and very deep–as much as two hundred feet in places. Both banks for a good deal of over a hundred miles, are shorn of their timber and bordered by continuous sugar plantations, with only here and there a scattering sapling or row of ornamental China-trees. The timber is shorn off clear to the rear of the plantations, from two to four miles.” In the early fall, these sugar plantations harvest the crops of sugar cane, leaving behind the stalks–the bagasse—“into great piles and set fire to them..” Twain reported. He described deep embankments, set back from one hundred feet to thirty feet, along the river with walls rising ten to fifteen feet on either side, and, when the damp bagasse started to burn slowly “You find yourself away out in the midst of a vague dim sea that is shoreless, that fades out and loses itself in the murky distances; for you cannot discern the thin rim of embankment..The plantations themselves are transformed by the smoke and look like a part of the sea. All through your watch you are tortured with the exquisite misery of uncertainty.”

Already in the time of Mark Twain, the slow narrow stretch of River wending its way to the Gulf of Mexico was an “alley,” and seasonally it would become a pipeline filled with smoke. In 1901, oil, already a valuable commodity, was discovered in Louisiana. Wells were dug and derricks erected. One can imagine how discovering an exploitable natural resource would impact a state still not recovered from the Civil War. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, oil had been refined and used for kerosene and for oil lamps, and when gasoline powered cars began to be a major factor in transportation, demand soared. Nevertheless, the state of Louisiana was vigilant enough to begin regulation of the refineries by 1906, forbidding oil and gas refineries to allow wells to burn and spew pollution into the atmosphere. But the discovery of oil did not make the state rich, and it was governor Huey Long who in 1928 attempted to raise money for paved roads for the people and textbooks for the children by taxing oil five cents per barrel. Owned by Standard Oil, the largest refinery in the world was located in Baton Rouge, and the company was quite capable of fighting back. The industry donated large sums of money to the legislators of Louisiana–$20,000 a vote, a large sum of money at that time–and the lawmakers obediently voted down the proposed tax. Long was driven from office shortly after his corrupt attempts to be a populist. He briefly had a second chance to succeed as a politician and became a senator in 1932. In 1935, he was assassinated. The power of the oil interests in the state in the late 1920s would not only increase, despite any attempts by Huey Long to make them share the proceeds, and that level of power would pale in comparison in the 1950s. During this decade, oil replaced coal as the most important natural resource in the world. Not coincidentally, it was in the 1950s that the parish of Baton Rouge voted to rezone the area from agricultural to industrial and the plantations were replaced with plants and the smoke from the fires became clouds of chemicals. And also not coincidentally, the inhabitants of the lands impacted by the oil industry were African-Americans, descendants of slaves, whose ancestors had probably worked on the plantations along the river, who were impacted the most. These were voiceless people, who were not allowed to vote and they could only submit in silence.

Richard Misrach. Restored Slave Cabins, Evergreen Plantation, Edgard, Louisiana (1998/2012)

Writing for The Bitter Southerner, journalist David Hanson, noted that the inhabitants of the town of Morrisonville, the descendants of freed slaves, were simply moved out of the way of a Dow Chemical Plant in the 1980s so that the company could avoid costly lawsuits from pollution–a leak or an explosion–brought by the townspeople. The decision of industrial giants, both petro and chemical, to move people out of harm’s way has become common practice in the state. For decades, these businesses insisted that they did not need regulation, because they would take care of their own waste problems. In his article “An Incomplete Solution: Oil and Water in Louisiana,” Craig E. Colten discussed the series of calamities that have hit Louisiana, from hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005 and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 to catastrophic floods in 2011, noting that highly dangerous and toxic industries that dominate Louisiana are located in areas vulnerable to destruction. This dual threat of poisonous plants and eroding wetlands and increasing violent weather events has produced what the author calls a “sacrifice zone.” Richard Mirach had already examined the zones in the American West, “sacrificed” by the United States government in the name of the Cold War. It was as if these deserts had been wounded in the service of their country. However, in Louisiana, there was no noble higher calling or cause for the sacrifice in Louisana.

Colten stated that “..an environmental “sacrifice zone” was a “..term derives from the study of traditional agricultural practices where cultivators deliberately degraded one area to increase productivity in another area, but scholars have begun using the term in explicitly accusatory ways to refer to areas degraded by modern industrial societies in the pursuit of economic and military gain. Environmental degradation in the lower Mississippi River industrial complex was not the result of a coordinated assault; rather it reflected negligent behavior by industries and government authorities. And significantly, those behaviors defied what contemporary trade literature presented as good industry practice. Sacrifice zone here refers to the result of disconnected actions that over time had an undeniable and lasting cumulative impact..As refineries transformed crude oil into marketable products, operators and regulators discounted the known costs of environmental damage. The gradual buildup of Louisiana’s chemical corridor, the dispersed geographic arrangement of the corridor, and the gargantuan diluting capacity of the Mississippi River all contributed to decisions about plant locations, waste management, and, ultimately, to the creation of a sacrifice zone. Over time, however, the number and size of petrochemical plants and the increasingly hazardous discharges into the river forced a reconsideration of the prevailing dogma of simply isolating dangerous facilities. Likewise, incremental adjustments to pollution regulation proved inadequate as industrial growth and waste releases greatly outpaced the capacity of on-site controls. Industry neglected to live up to its proclaimed safety and pollution-control capabilities.”

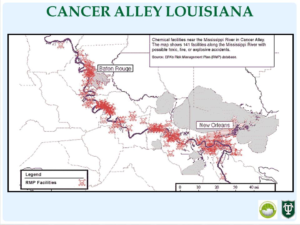

When the High Museum tapped Misrach photograph the South in 1998, the 80 mile stretch along the Mississippi had one hundred fifty plants along its banks. Doing simple math, these figures work out to two plants per mile, hopefully on opposite sides of the bank. Interestingly enough that year was also the year of a rare victory in the constant battle between the cancer-prone residents and the industries that want to extract the wealth beneath their feet. In a report on “Cancer Alley, Louisiana,” Dorceta E. Taylor, wrote,“The population of cancer alley is primarily African-American and low-income. Despite the large number of industrial facilities—more than 136—unemployment is high in many communities and most residents do not have a college education. Nevertheless, the inhabitants of cancer alley have been organizing to limit the siting of noxious facilities in their neighborhoods. The most famous case of community resistance occurred in Convent, where, in 1996, Shintech announced plans to build a $700 million chlor-alkali vinyl complex that would be permitted to emit 611,700 pounds of contaminants into the air. The battle between Shintech and Covent garnered international attention. Finally, in 1998 Shintech decided to abandon its plans to build a plant in Convent.”

These were the conditions when the photographer began his education on environmental conditions of the South. There were many “sacrifice zones” in the region and he decided on one of the most notorious, Cancer Alley, Misrach stated, “I’d never heard of this area..And when I finally saw the landscape, I was shocked. It was really extreme—the amount of industry along the river and the poor communities living there—I couldn’t believe it actually existed.” He returned in 2010 in preparation for the follow-up exhibition, Revisiting the South in 2012 and saw that time had stood still. He said, “It was impossible to tell if it’d gotten worse or better..It looks the same. It feels the same. The roads are still below par, and the schools are as well.” He added that it wasn’t just the sights of the polluted waters and banks that were disturbing it was elements that his photographs could not convey. “What’s not shown is the constant stirring sound; I’m amazed people can work..And the smells, from the gasoline stench to the chemicals in the air. That’s what you can’t see.” MIsrach was fresh from his journeys to the sacrifice zones of the West featured in his series Desert Cantos, when he began his project in 1998. He stated, “People were living side by side with these great industrial behemoths. I’d always thought of industrial sites as sacrifice zones, in that they would be off in an isolated area, like in Nevada with the nuclear test site in the middle of nowhere. It never occurred to me that people would live within feet of these toxic environments. I was really shocked to see that in the United States. And so in 1998, I photographed up and down both sides of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, making several trips.”

Today those intrepid travelers who would dare to paddle their canoes down the Mississippi and reach the “Lower Mississippi River Water Trail,” this rather chilling advice is given, “The last 225 miles of the Lower Mississippi River is also the most dangerous and most demanding. Warning: for expert paddlers only. The fecund wilderness of the sprawling Mississippi River floodplain disappears above Baton Rouge and is replaced by a chaotic global shipping lane. You will have to paddle several hundred miles of choppy crowded water sharing the main channel with sea-going freighters, cargo boats, re-supply vessels, and endless fields of barges as they fleet up for the long distance journey back up the river. Commonly known as Chemical Corridor, but also described as “Cancer Alley.” Paddlers might want to add an oxygen face mask to their equipment list here and maybe a hazmat suit. Seriously. You will be camping next to refineries and chemical plants, and lots of coal-fired power plants. More toxins are dumped in the river here than any other piece of river in America. No more remote camping, no more swimming, no more quiet sections of river teeming with wildlife. This is a section of the Mississippi you paddle just to get through it.”

Misrach revealed “Cancer Alley,” an environment sacrificed, given over, to the petrochemical industry so that the rest of America could drive its cars and heat its homes and use an untold number of petroleum-based products. The 1998 commission resulted in ten large photographs and some forty smaller ones, he also turned over to the High Museum. Around 2010, the Museum asked Misrach to “revisit” the disaster, to edit the earlier work and produce new images. The photographer said in a conversation with Kate Orff for Aperture, “We agreed that it would be really interesting for me to revisit and photograph, but also, if I was going to do this, I didn’t want to just show the pictures; I wanted to do some sort of intervention that reached out and maybe had some constructive results (like what I attempted in my book Bravo 20, which proposes the conversion of a bombing range into a national environmental park). I started off with some pretty idealistic fantasies and drawings about how the area could be reclaimed.” The fact that Misrach could see no positive changes in the region, despite numerous lawsuits over the clusters of cancers along the river, suggests both the money and power of the industry that dominates Louisiana and the complicity of the rest of that nation in laying waste to the region. On the occasion of his “re-visit” to the state, Misrach said, “Throughout Cancer Alley, homes, schools, and playgrounds are situated yards from behemoth industrial complexes. Residents within a one-mile radius of factories are subjected to significant air and water pollution as well as noxious odors and industrial noise. Many communities along the River Road live in abject poverty. The quality of life in Louisiana has been rated one of the lowest in the nation. In contrast, extremely favorable taxation policies have helped draw industry to the region. One-quarter of the nation’s petrochemicals are manufactured here.”

In commenting on the 2012/3 tour of the “Revisiting the South: Richard Misrach’s Cancer Alley” exhibition at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford Univesity, the gallery wrote that in the photographs, “..The petrochemical industry reveals itself as an omnipresent and brazen specter through the photographs’ rusted pipelines, mammoth tankers, and tangles of steel, concrete, and smokestacks belching noxious fumes and toxins into the air and water. Looking through Misrach’s lens, the viewer comes to realize that Cancer Alley’s industrial corridor—which produces almost one-third of America’s gasoline, plastics, and other chemicals—is generating a lethal combination of pollutants that is quietly deteriorating local communities and watersheds, leaving behind only cryptic relics of what was once a richly diversified past.”