PHOTOGRAPHY IN THE VICTORIAN ERA

Roger Fenton (1819-1869)

Royal Patronage and Photography

By the middle of the nineteenth century, the dominate power in the world was Great Britain, a pair of small islands off the coast of continental Europe. Thanks to its powerful Navy and the moat of the English Channel, England was separated enough to develop a culture that was self-sufficient enough to create a strong central government, a constitutional monarchy, that guided an Industrial Revolution that was unequally on the Continent. In the middle of the nineteenth century, the scope and the reach of the imperialism of the island nation had not yet reached its apex, and Britain was consolidating its grip on its possessions through occupation and colonialism. Presiding over the expanding empire was a small woman, Queen Victoria (1819-1901), who would have a reign long enough to witness the transition from horse drawn carriages to automobiles. She married a member of the minor European nobility, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha (1819-1861), who was quite interested in all things technological, including the new invention of photography. Lacking any real legal power, Prince Albert was an intelligent man who managed to make his presence felt in positive ways to serve the people ruled by his wife. Perhaps his greatest and certainly his most lasting contribution to the British people was the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London’s Hyde Park. The date 1851 is significant being only three years after the unrest of the Revolutions of 1848 which had roiled Europe. Prince Albert wisely advised the British throne to hear the grievances of the people rather than drive them to rebellion and this exhibition, located in a nation that had avoided revolutionary uprisings, was designed to celebrate the return of social and political peace in Europe. Designed by Joseph Paxton (1803-1865), the landscape architect for the Duke of Devonshire, the basilica shaped structure was built entirely of panes of glass mounted on an iron armature. To demonstrate that the glass building was safe for the public, Prince Albert had a contingent of soldiers march inside galleries. Reassured, crowds surged to the “Crystal Palace” and the display of the industrial and cultural and artistic production of all nations who cared to participate. For the first time two traditions were brought together, that of handicraft and art and that of machine-made machines. For traditionalists, such as designer William Morris, the manufacturing of consumer goods in a factory was a horror, for the industrialists, the Exhibition was full of promise for the future. Standing at the crossroads, halfway between art and science, photography was awkwardly placed in Section X, in department of machines and instruments, along with clocks and surgical tools. Perhaps due to the private and largely amateur status of paper photography in England, for the British audience, the Exhibition would have been their first opportunity to view this photographic process. Organizer Sir Henry Cole (1808-1882) was one of the early supporter of photography and it could be argued, with seven hundred and seventy images from six nations on view, that the Great Exhibition in London was the first international exhibition of photography. The nations with the most impressive submissions were Great Britain and France and America. The French contributions included paper photography from the major photographers and their work overshadowed that of the British. The comparison between the French who had the freedom to develop the paper process and the English who were hampered by Talbot’s patents caused a stir among those who understood the necessity of sharing technology. On the other hand, in England, there was a sizable contingent of observers who lamented that the photography exhibited emphasized art and pleasure rather then the “usefulness” of photography which should be deployed for the purposes of science. That said, the public shaming of the British photographers in the realm of paper photography in the very land where the Calotype had been invented inspired an up-and-coming photographer named Roger Fenton to go immediately to France to learn what his French counterparts knew. On the surface, it is interesting, in an age dominated by Daguerreotypes, that Fenton was so struck by the paper photography of the French. Certainly he recognized that the French were technically ahead of the British. His views were ostensibly shared by the British jury which felt that nevertheless British photography was superior to those of France and America and awarded the majority of the medals to their countrymen. However, to assert that Fenton understood the superiority of the French was not a given, for he was a failed painter who was realizing he could not gain recognition in the Royal Academy. Even worse he was a married man with children and he needed a new occupation that allowed him a steady income. Turning to photography seemed an obvious choice. The quality of the photography in the Great Exhibition would have been a revelation to Fenton, not just because of Gustave Le Gray’s use of waxed paper but also because of the artistic approach of the French. Although in its embryonic form, Frederick Scott Archer’s (1813-1857) new photographic process, collodion, was on view with several images made from negatives on a “film” of liquid spread over a pane of glass where it hardened or solidified. Fenton was lucky enough to be struck with the idea of going into business as a photographer at a good time. In the next few years while he was learning his craft, photography would move decisively away from the Daguerreotype in 1854, when Archer released the chemistry of collodion to public use and Talbot gave in to the inevitable and decided to not renew his inhibiting patent. By mid-century, photography was freed from its past and could move to its future. Fenton was no stranger to France. Drifting out of law and into painting, the son of England’s newly wealthy middle class had studied in the ateliers of Paul Delaroche and Michel-Martin Drolling, a student of Jacques-Louis David. But when he returned to England, Fenton found a new mentor and made the acquaintance of the painter Ford Maddox Brown (1821-1893), who was linked to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. With a checkered background in painting combining the juste milieu, late Davidian classicism and the avant-garde moment that refuted academic painting, it was no wonder that Fenton found so little traction at the Royal Academy and one can only surmise that that his willingness to partake of many different aesthetics and artistic philosophies enabled him to consider switching to photography. In the fall of 1851, with Gustave Le Gray (1820-1884), he was in good hands . Le Gray, now a veteran of months of photographing historic French architectural sites for the Mission Héliographique, took on pupils and was generous (unlike Talbot) with his knowledge. It should be noted that, even at that time, Fenton was still practicing law, but he was beginning to make use of his contacts and connections. Although he appeared to be at loose ends, without life purpose, Fenton was well-protected in his professional waywardness. Still a decade away from the American Civil War, his father was a very wealthy cotton manufacturer and the family money gave Fenton sufficient polish and poise and self-confidence to maneuver through the society of those interested in photography, from the lordly Talbot to the high-born Prince Albert himself. What is interesting about the career of Fenton is the extent to which Talbot’s recalcitrance aided his meteoric rise. No sooner did he return from France Fenton established photographic organizations which mirrored those in France. As early as 1847 he founded the Calotype Club and in 1852 he published a “Proposal for the Foundations of a Photographic Society” that would mirror the Société Héliographique and apparently aimed to end the split between amateurs and professionals or upper and middle class practitioners. Then in 1853 he founded the Photographic Society, later renamed as the Royal Photographic Society and in 1854, he became the first official photographer for the British Museum. But in the midst of all this organization building, in 1852 he managed a photographic coup when his long time friend, the engineer Charles Blacker Vignola, asked him to accompany him to Russia where he was building a bridge for the Czar Nicholas over the Dnieper River. Fenton’s task was to record the stages of bridge building and he was able to find the time to travel to St. Petersburg, Kiev, and Moscow. It is generally agreed that he was the first to photograph the Kremlin. The method he used for these waxed paper prints was learned from Gustave Le Gray. From the start it is clear that Fenton had made choices as a photographer that were surprisingly in contrast to those of Le Gray whose documentations were always artistic. Fenton made himself into a straightforward documentary photography minus the poetry or the possibilities for interpretation opened by Le Gray. Fenton provided information about the Kremlin and only information and the series of images that came out of Russia were not just a surprising turn for an artist but also indicative of the direction of the rest of his career. South Front of the Kremlin from the Old Bridge (1852)

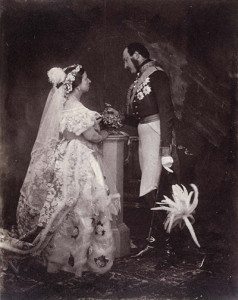

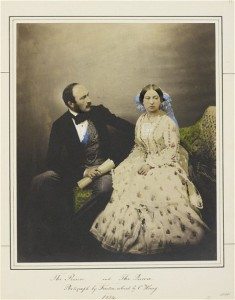

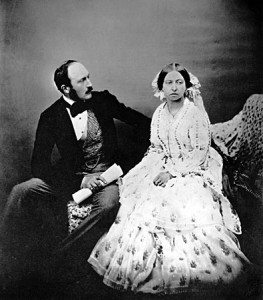

The ever busy and enterprising man of many parts, Roger Fenton, and fellow painter Thomas Seddon established the North London School of Drawing and Modeling in 1850 with the intention of educating working class men. It is at this early point in his career that Fenton came into contact with Prince Albert who was a patron for the School. This connection would prove invaluable for Fenton who, like Le Gray, tried to go into the business of being a professional photographer in partnership with Philip Henry Delamotte. Delamotte helped Fenton organize an exhibition of his Russia photographs at the Society of Arts. But Fenton and Delamotte ran into the same problems that had been experienced by Le Gray–they could not compete in a market over-ridden with thousands of cheap photographs. The public simply was not educated enough to differentiate among the various kinds of photography and the existing quality levels and intents of the makers. The British Museum came to the financial rescue in 1854 with a commission to photograph some of its extensive collection. The task was basically that of recording and documenting with a scientific accuracy and visual clarity objects such as Assyrian tablets. According to Sarah Greenough in her 2004 article, “A New Starting Point: Roger Fenton’s Life,” the years long project resulted in thousands of salt print images. While the Museum was pleased with this work, it should be noted that Fenton established a precedent for how museums should record and catalogue their possessions. But as Greenough pointed out, an even bigger break came with way of Fenton, thanks to his many connections. In that same year, Fenton and Sir Charles Eastlake (1793-1865), who headed the Royal Academy, were designated to guide Prince Albert and Queen Victoria through the first exhibition of photography sponsored by the Photographic Society (future Royal) and explain the art and practice of photography to the rulers. Fenton reconnected with Prince Albert and made the acquaintance of the Queen who was impressed with the photographs and with Fenton. Both of the Royal couple were fascinated with photography and were avid collectors of these new artists. They seemed to have understood that photography could take a significant role in publicizing the Royal Family, and Victoria and Albert were photographed throughout their lives. At first the Queen disliked the way she looked in a photograph but, over time, she learned how to present herself as photographic subject but always as the Queen. However, the Royal patronage of Fenton for private purposes was, as Greenough pointed out, because of his suave, educated manner. The Royal Family allowed him into their private lives. Victoria and Albert employed a number of more of less official photographers but mostly for official purposes. Fenton’s brief as a photographer and as a chronicler of Royal life was unique at that time: he was allowed into the personal space of the Royal Family. Although he portrayed Victoria and Albert in the first photograph which displayed the Queen and her Prince Consort as a ruling couple, Fenton photographed Victoria and Alberta and their many children engaged in family activities in the private settings of Buckingham Palace. Victoria and Albert, May 1854

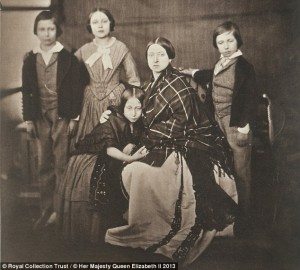

Many of the photographs are dated June 1854 but the images range from the posed to the causal to the very formal. This was a formal age and there is no doubt that while Victoria intended to document her family for primate purposes and to create a record of her children’s growth and development, the assemblages of family members were carefully thought out. Queen Victoria and Her Five Children (1854)

The Princesses Helena and Louise (1856)

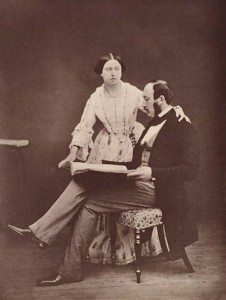

The pictures of Victoria and Albert as a couple are the most interesting–a small and powerful Queen and her tall and powerless husband, entwined in an awkward arrangement in a patriarchal society that resulted in self-conscious poses that were unconsciously revealing of their very different situations in life. By all accounts the Royal Pair were a devoted couple who valued family life. But war clouds were gathering in the Crimea, and Albert, ever wary of foreign wars and imprudent adventure, warned against intervening in what was a dispute between the Russians and the Turks. His advice would not be heeded and Roger Fenton’s next assignment was to photograph a war, making him one of the first photojournalists and one of the first photographers of war. The next post will discuss Roger Fenton taking on an impossible task: pleasing a patron–Prince Albert–and recording a pointless war without bias. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.