SIR JOSHUA REYNOLDS (1723-1792)

Royal Academy in England: Classicism and Conservatism

Although the Royal Academy in England was established one hundred years later than the Royal Academy in France, England’s academic system was part on an ongoing rivalry for dominance between the two nations. By the late Eighteenth Century, when the Royal Academy was established by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792) in 1768, the idea of national identity was being formed. A major figure in organizing his fellow artists in London and in petitioning the government to found the Academy, Sir Joshua was its first president. Along with colonial and military power and economic power, artistic achievement was also becoming part of a nation’s demonstration of superiority. Our of an original thirty four artists, a new establishment elevated fine art from a private affair to a place of public pride. A hundred years earlier, the Royal Academy in France was founded for the purpose of creating a cultural hegemony over Europe, and, regardless of aesthetic shifts and political changes, the French reigned supreme over the English in the decorative arts, fashion, and the fine arts until well into the twentieth century. However, the Royal Academy in England reflected the very different social and cultural and even economic milieu of the nation. An island and a naval power, Great Britain was well on its way to building a global empire while France dreamed of conquering the continent. The British people suffered a great loss when the Americans broke away from their Empire and established their own independence, but the “cousins” mended their fences over time and the English continued building the Empire.

The President of the Royal Academy, Sir Joshua Reynolds, was a portrait artist, and, in England, portraiture was one of the major genres, compared to France where history painting reigned supreme. Sir Joshua had studied in Rome and had inhaled the “grand manner” in art, which, in England, translated to an updating of Renaissance art for a modern era. The artist was situated in an interesting time in England as it transitioned into a modern nation while it retained its aristocracy and its royal family. Although the King who approved the idea of the Royal Academy, George III, the ruler who “lost” America, did not care for the work of Reynolds. He was allowed to paint the King only once. The occasion was the establishment of the new home of the Royal Academy at Somerset House in 1780, and one can imagine that the King could not avoid this commission from the President of the Academy. The “Grand Manner” was supposed to be used for history painting but Sir Joshua adapted its flourishes to the art of portraiture. This portraiture was, of course, designed for the aristocracy who saw their own status and erudition reflected in the portraits executed by Sir Joshua. The simple Grecian design of the dresses the women wore referenced ancient sculpture and their poses also copied classical stances. The sitters were posed against a backdrop of classical architecture, indicating their hereditary nobility and worthiness to their station. To offset the artificiality of the classical references, Reynolds would include the English countryside, symbolizing the lands owned by the powerful aristocrat. The artist considered himself walking in the footsteps of his predecessors, such as Sir Anthony van Dyke, painter of kings. However elevated his clientele, Sir Joshua was nothing if not a businessman and he applied his grand manner to portraiture, elevating the genre and speeding his talents across country houses and towns homes. He painted over two thousand portraits and assorted paintings and was capable of painting a hundred and fifty paintings a year. A recent book, The Life and Times of the First President of the Royal Academy, Ian McIntyre noted that contrary to his rather conservative subject manner, Sir Joshua was an experimenter when it came to painting. His colors had an alarming tendency to fade and today many of his portraits look washed out, pale ghosts of what they once were. He also painted wet into wet, probably because he worked in haste, rushing from one commission to another.

Sir Joshua Reynolds. Mrs Hale as Euphrosyne (late 1700s)

The art writer for The Guardian, Jonathan Jones, discussed why it is that we have little appreciation for Reynolds the artist today. His theory is that the artist painted those in power and that today we are wary of such figures. Contemporary audiences prefer Thomas Gainsborough, a younger artist and a great rival to Reynolds, simply because Gainsborough’s approach to his subjects were novel and arresting, while Reynolds followed a classical formula for his portraiture. As Jones noted, “Quotation from classical art is not just a tic in Reynolds’s portraits – it is a philosophy. When George III founded the Royal Academy in 1768, there could really be only one choice for its president, even though the king didn’t like the Whiggish Reynolds. And Reynolds’s most lasting contribution to British art was not, in the end, his paintings – it was the series of lectures he gave to graduating students of the Royal Academy’s school. Reynolds’s Discourses On Art are definitive expressions of neoclassicism. The 15th-century Renaissance revived the art of ancient Greece and Rome but had only the roughest idea of the difference between them. The 18th century isolated the moment of classical perfection, in Athens in the 5th century BC. Reynolds’s ideal was Phidias, the ancient Greek sculptor credited with the design of the Parthenon and its frieze, the supreme aesthetic achievement of the ancient world. (These were the “marbles” that Lord Elgin brought to Britain so controversially at the beginning of the 19th century.) Phidias portrayed not the changing visible trappings of nature, the disfigured mess of the way things look (Reynolds looks down his nose at people who do, such as Hogarth) but something underneath the surface – “Ideal Nature”, the divine form of perfection. Reynolds urged the modern artist to do the same.”

Although some of his portraits were quite novel and interesting, today the artist is best known for his writings and for his power and control over the Academy. Even after his death in 1792, his influence and his conviction that painting should be in the “grand manner” remained, making it difficult for new ideas to emerge. Sir Joshua was president of the Royal Academy until his death in 1792 and for over fifty years, his discussion of art and aesthetics, Discourses on Art, (1769–90), actually fifteen separate discussions, was the main source for understanding art in England. In the introduction to this “wise little book,” the Academy stated that “..inaugural discourses by Sir Joshua Reynolds, on the opening of the schools, and at the first annual meetings for the distribution of its prizes. They laid down principles of art from the point of view of a man of genius who had made his power felt, and with the clear good sense which is the foundation of all work that looks upward and may hope to live. The truths here expressed concerning Art may, with slight adjustment of the way of thought, be applied to Literature or to any exercise of the best powers of mind for shaping the delights that raise us to the larger sense of life. In his separation of the utterance of whole truths from insistence upon accidents of detail, Reynolds was right, because he guarded the expression of his view with careful definitions of its limits.”

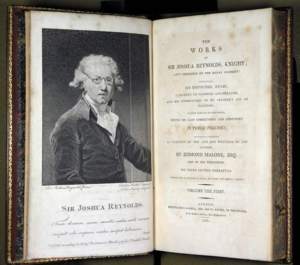

Sir Joshua Reynolds. The Works of Sir Joshua Reynolds, Knight

On the occasion of the Distribution of Prizes on December 11, 1769, Reynolds discussed the “study of painting” which he divided into three “distinct periods.” “This first degree of proficiency is, in painting, what grammar is in literature, a general preparation to whatever species of the art the student may afterwards choose for his more particular application. The power of drawing, modelling, and using colours is very properly called the language of the art; and in this language, the honours you have just received prove you to have made no inconsiderable progress. When the artist is once enabled to express himself with some degree of correctness, he must then endeavour to collect subjects for expression; to amass a stock of ideas, to be combined and varied as occasion may require. He is now in the second period of study, in which his business is to learn all that has hitherto been known and done. Having hitherto received instructions from a particular master, he is now to consider the art itself as his master. He must extend his capacity to more sublime and general instructions. Those perfections which lie scattered among various masters are now united in one general idea, which is henceforth to regulate his taste and enlarge his imagination. With a variety of models thus before him, he will avoid that narrowness and poverty of conception which attends a bigoted admiration of a single master, and will cease to follow any favourite where he ceases to excel. This period is, however, still a time of subjection and discipline. Though the student will not resign himself blindly to any single authority when he may have the advantage of consulting many, he must still be afraid of trusting his own judgment, and of deviating into any track where he cannot find the footsteps of some former master. The third and last period emancipates the student from subjection to any authority but what he shall himself judge to be supported by reason. Confiding now in his own judgment, he will consider and separate those different principles to which different modes of beauty owe their original. In the former period he sought only to know and combine excellence, wherever it was to be found, into one idea of perfection; in this he learns, what requires the most attentive survey and the subtle disquisition, to discriminate perfections that are incompatible with each other.”

In an essay on the occasion of an exhibition, “Sir Joshua Reynolds: The Acquisition of Genius,” at the Plymouth City Museum and Art Gallery, Sam Smiles wrote, “As President of the Royal Academy, Reynolds was in a good position to argue for the intellectual and cultural worth of the fine arts. The Discourses, although ostensibly addressed to the students of the Royal Academy, were designed to make a contribution to contemporary discussions on aesthetics, the history of art and the cultivation of taste. Reynolds’ characterisation of the artist as a professional, combining intellectual understanding with facility of hand, his insistence that genius can be taught, may be understood as necessary strategies within a wider campaign to raise the standing of the artist in Georgian England. Throughout his Discourses he is at pains to present painting as a liberal profession, combining intellectual powers with creative imagination, and thus quite distinct from what its detractors would call merely a mechanical trade, reliant solely on technical skills and the servile imitation of reality. In essence, what Reynolds proposes is that artists have the ability to conceive a subject imaginatively and can convey its essential quality or significance by employing a generalised treatment of visual appearance, beyond any concern with minute details. This ability is ‘an instance of that superiority with which mind predominates over matter, by contracting into one whole what nature has made multifarious.” Sir Joshua was succeeded by the American, Benjamin West, who remained loyal to King George III. The purpose of the Academy was the same as its counterpart in France: to maintain the quality of training in order to improve the status of the arts and crafts. Sir Joshua set up the hierarchy of painting with history painting on top and genre and still life painting at the bottom. Although Reynolds referred to the “cold painter of portraits,” portraiture enjoyed greater prestige in England than in France, not the least because Reynolds was a portrait painter, along with his colleague Thomas Gainsborough. In another deviation from the French, the Royal Academy’s founding members included two women, Angelica Kauffman and Mary Moser. However, it would be 150 years before another woman would be allowed to cross the Academy’s portals.

Angelica Kauffmann. Ferdinand IV, King of Naples, and his Family (1783)

Following the French example, the English set up free exhibitions of paintings in order to encourage an English school of painting. The need to have a specifically “English” art was, of course, a challenge to the French who transcended the idea of a national school so great was their complete dominance in the arts. The Louvre Museum was instituted, first, to give the new “citizens” of the French Republic access to art, and second, to display the treasure trove of Napoléon’s loot for the public. In contrast, the National Academy in England was specifically begun to encourage an “English” school of painting. The National Gallery was founded in 1824, based upon the collection of paintings owned by John Julius Angerston. For decades the collection of the National Gallery grew from large bequests from other collectors, such as Joseph Mallord William Turner and Sir Robert Peel, with Charles Eastlake augmenting the private collections with acquisitions from Europe. In 1897, thanks to Henry Tate, the Gallery moved to its permanent location at Trafalgar Square. Sir Joshua Reynolds followed the French example by using classicism as the norm in the Royal Academy. Classicism, in this late Baroque or Rococo period, was based upon the Italian grand manner art, or gusto grande, based upon the art of Raphael (spelled “Raffaelle” in the time of Reynolds). Although based in nature, classicism refined, idealized and transcended nature. Like at the French Academy, the role of high art was to elevate and educate the viewer as to the proper moral state of mind. Young men would be educated in the Academy to produce this classically styled art by older masters. The “directors,” who would guide the “boys,” as he called them, away from “negligence,” “frivolous pursuits,” “corruption” (from foreign sources), “sloth” and towards “diligence” and “scrupulous exactness.”

The educational program included, not so much copying directly from the masters, but learning from models from the Italian and Flemish schools. Like their French counterparts, the English students of the Academy were sent to Italy where they could study Italian grand manner art in situ. Once they were established as painters, the artists would show at exhibitions where their “Diploma” work, destined to become part of the Academy’s collection, would be shown. The artist then rose through the ranks to an Associate Royal Academician to a Royal Academician, a status where fame fortune and knighthood could be obtained. In many ways the seven Discourses of Reynolds were based upon the Academy’s collection of drawings of Raphael—mentioned over and over—as examples for the students to study. For Sir Joshua true Beauty was based upon “a correct and perfect design,” which subordinates “minuteness” and “smallness” and ornamentation. The “grand manner” of Reynolds aimed to treat the high-minded content in a generalized (or universal) fashion, with details subordinated. Reynolds discussed “genius” and “taste,” but not with the notion of artistic freedom or contemporary life but within the realm of antiquity and Renaissance artists. He recommended Nicholas Poussin and Claude Lorraine, both classicists, as artists who continued the grand manner. Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the ideas of Sir Joshua Reynolds dominated the English art scene and academic art in Great Britain was always based upon classicism. Only the writings of the art critic, John Ruskin, who published Modern Painters (1843–1860), which reflected the “modern” and the inevitable changes in art were capable of challenging the first President of the Royal Academy.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.