Creating a Language for the Revolution

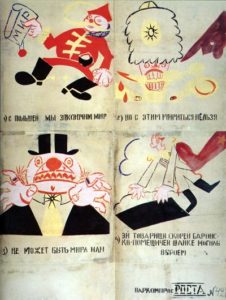

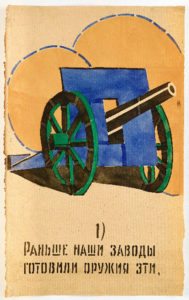

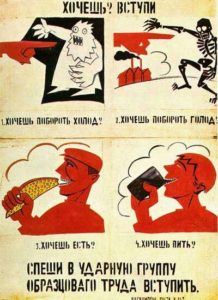

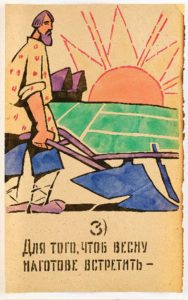

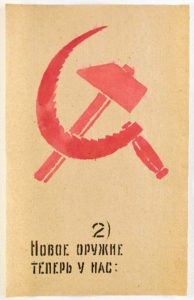

The ROSTA Windows

In 1917, Russia was a nation no longer a nation, but an empire unraveling, torn between a weak provisional government and rear guard resistance of the so-called “White Russians.” The Russian Empire collapsed under the unbearable weight of an un winnable war, resulting in a wholesale refusal to carry on under the weak and ineffectual Czar. This was the February Revolution, which, according to the new calendar happened in March, and it was a simple and spontaneous strike, a rejection of not just an unwanted war but also a failed ruler. Despite the will of the people who wanted to extricate themselves from the Great War, the Provisional government continued to participate, leaving the door open to continuing discontent and further rebellion. Even though the Czar abdicated, no doubt hoping for a peaceful retirement, another coup took place in October Revolution (November). The arrival of the “Reds,” or the Communists, under Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924) pushed the temporary regime aside and established a new kind of revolution, the first Marxist government, led by the Bolshevik Party. Once Lenin had negotiated a withdrawal from the War–at great cost to Russia–making peace with Germany, a five year struggle for the soul of the new nation began with the Whites. This fight was waged militarily and politically, but Lenin, recognizing the power of the visual image, called upon artists to join the conflict as part of the propaganda effort to educate the Russian people on the merits of Communism.

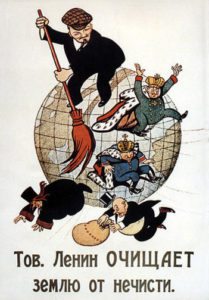

Comrade Lenin is Sweeping Scum off the Earth

At the time of the Revolution, “Russia” consisted of a few cities, located mostly in its western half. it was here in the municipalities and the urban centers, that culture, both high and low, was produced, mostly for a literate population. However, the new Soviet Union was a huge and vast expanse of land and forty five percent of its inhabitants were illiterate. The stupefying fact that half the people could neither read nor write was an outgrowth of an elitist system in which the upper classes spoke French and the vernacular Russian speakers, the middle classes, strove to produce a specifically “Russian” culture with Russian roots and history. Adding to that division between classes was the total neglect of the lower classes who were left to fend for themselves and remain uneducated. Under the autocratic and ruthless rule of the Czar, the illiteracy hardly mattered, but when the Bolsheviks came into power, they had to fight a civil war to consolidate that power. Part of the war, beyond actual fighting, involved convincing people–all the people–of the benefits of a revolution that promised the level the class system, eliminate all traces of elitism and former loci of collusion, including religion, and to redistribute the wealth and property of the aristocracy. It would be less a matter of convincing the people that this revolution would be preferable to the Czar and more a commitment to informing the people as to the progress of the Reds in their battle against the Whites.

ROSTA poster

The solution was straightforward propaganda, an information campaign that would announce the new government and explain its new benefits for all. Lenin expressed the scope and urgency of the task, published in the Bulletin of the All-Russia Conference of Political Education Workers in 1920:

The transition from bourgeois society to the policy of the proletariat is a very difficult one, all the more so for the bourgeoisie incessantly slandering us through its entire apparatus of propaganda and agitation. It bends every effort to play down an even more important mission of the dictatorship of the proletariat, its educational mission, which is particularly important in Russia, where the proletariat constitutes a minority of the population. Yet in Russia this mission must be given priority, for we must prepare the masses to build up socialism. The dictatorship of the proletariat would have been out of the question if, in the struggle against the bourgeoisie, the proletariat had not developed a keen class-consciousness, strict discipline and profound devotion, in other words, all the qualities required to assure the proletariat’s complete victory over its old enemy.

ROSTA poster

During the Great War, mostly due to German misinformation, the word “propaganda,” once a neutral and positive word, gained a negative connotation by the 1920s, but never in Russia. The Soviets used propaganda during the entire life of the Union as a vital tool to control public opinion. As soon as Lenin became the leader a broad strategy emerged called “agitatsiya-propaganda,” or political agitation and propaganda, or “agit-prop.” Agit-prop was dedicated to raising the consciousness of the people, in the Marxist sense, to inform the people of their exploitation at the hands of their masters so that their eyes would be open to the truth of their oppressed condition. In his book, Komiks: Comic Art in Russia, José Alaniz noted that the earliest example of Civil War art was a series twelve posters showing the workers’ consciousnesses being “raised” when the peasant is freed from his blindfold and “sees the truth.” Alaniz described one poster, Once Upon a Time There Lived the Bourgeoisie, as resembling a comic strip with eight panels, a format that would become familiar to the public as a progression from one cell to the next. Once the readers understood that the Bolsheviks were their benefactors, the powers that had set the peasants free, the lower classes could be joined in solidarity against the enemy, whether the Whites or an outside threat. To achieve the proper level of communication and education and consciousness raising, agit-prop was deployed as theater, as trains, as posters, as art forms of all kinds form verbal to visual. The agit-prop efforts were especially intense during the war between the Whites and the Reds, from 1917 to 1922, when the activities were less controlled by the government and more in the hands of the artists themselves. After the Bolsheviks consolidated their power, the agit-prop activities were formalized and brought under the command of the victorious regime.

ROSTA poster

From the very beginning of the propaganda campaigns, the question of the language of art came up in the form of a dialogue of sorts between artists and officials. Most avant-garde artists were enthusiastic supporters of the Marxist cause and worked hard to ensure the success of the new government, but their efforts did not always please the new masters. Artists and politicians are very different kinds of individuals with entirely distinct educational and cultural experiences. Artists such as Marc Chagall in Vitebsk celebrated the October revolution with his own fantastical version of traditional Russian luboks and Jewish imagery, but the authorities were not pleased with the green cows and blue donkeys, improbably flying through the air. The problem for the artists would be two fold: first, as in the case of Chagall, his or her imagination and singular perspective could interfere with what the government needed: a clear message to the people. Second, as in the case of Malevich, art that was too intellectually “advanced” or “avant-garde” was equally incapable of being recognized by the illiterate public as “art,” much less as communication. The artists were deeply sincere, willing to lay down their art in the service of the revolution, but they were also equally committed to their art and the logical outcomes of avant-garde art. This aesthetic outcome, as demonstrated by Malevich’s abstract Suprematism and Tatlin’s spectacular but unbuildable “monuments,” was not very useful to the government and its needs. As Raphael Sassower and Louis Cicotello pointed out in their 2006 book, Political Blind Spots: Reading the Ideology of Images,

..the avant-garde style of geometric abstraction typical to the experimental art of the pre-Revolutionary aesthetics..began to arouse objection from supporters of traditional representation imagery in both the artistic and government circles. Art historians associated with the government publication of posters for the military argued for realistic rather than abstract work. Workers, soldiers, and peasants drawn in squares, circles, and triangles were senseless images that couldn’t express the integrity of the revolution..Public decorations in the avant-garde manner, often referred to by Pravda reviewers as “the fashionable futurist style,” met with opposition as being incomprehensible and condemned as a mockery of the taste of the working class.

ROSTA poster

The most successful art form dedicated to the Revolution was the production of ROSTA posters, an outpouring of artistic enterprise that cranked out thousands of lithographs. Only a few of these posters survive today but they are the best examples of art made on the fly, responding to the urgent need of the Revolution to communicate with the people. The English writer Arthur Ransome had traveled through Czarist Russia in 1913, acquainting himself with the culture, learning the language and collecting Russian folk tales. The publication of Old Peter’s Russian Tales, (1916) took place during the War and, in fact, Ransome spent the four years in Moscow, reporting on the war. After the Great War, Ransome’s long stay in St. Petersburg, now Leningrad, and Moscow was considered valuable to his newspaper, the Daily News, and he began reporting on the Revolution. His book Six Weeks in Russia in 1919 ccontained an account of his encounter with agit prop. Ransome noticed that posters were everywhere:

When I crossed the Russian front in October, 1919, the first thing I noticed in peasants’ cottages, in the villages, in the little town where I took the railway to Moscow, in every railway station along the line, was the elaborate pictorial propaganda concerned with the war. There were posters showing Denizen standing straddle over Russia’s coal, while the factory chimneys were smokeless and the engines idle in the yards, with the simplest wording to show why it was necessary to beat Denizen in order to get coal; there were posters illustrating the treatment of the peasants by the Whites; posters against desertion, posters illustrating the Russian struggle against the rest of the world, showing a workman, a peasant, a sailor and a soldier fighting in self-defence against an enormous Capitalistic Hydra. There were also-and this I took as a sign of what might be-posters encouraging the sowing of corn, and posters explaining in simple pictures improved methods of agriculture. Our own recruiting propaganda during the war, good as that was, was never developed to such a point of excellence, and knowing the general slowness with which the Russian centre reacts on its periphery, I was amazed not only at the actual posters, but at their efficient distribution thus far from Moscow.

ROSTA poster

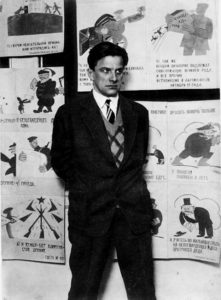

ROSTA stands for Russian Telegraph Agency (Rossiiskoe Telegrafnoe Aganstvo, or ROSTA) which was an organization that transmitted messages and the news across the nation. These agencies had windows which would be plastered with posters, changing hour by hour, “broadcasting,” as it were, accounts of the most recent events and the need to get medical vaccines and bulletins about the Civil War. The idea of the ROSTA windows being the ground for posters has been attributed to Mikhail Mikhailovich Cheremnykh (1890-1962), who created the first poster filled window. The images needed text and Vladimir Mayakovsky (1893-1930), a revered poet, supplied the slogans and phrases needed to inform the public in a succinct and direct form. As Mayakovsky said, “A machine like speed was demanded of us; it would often happen that a report of some victory at the front would come in by telegraph–and 40 minutes to an hour later, the news would be hanging out in the street, in the form of a colorful poster.”

Vladimir Mayakovsky

The posters were a collaborate production and most of the artists, such as N. Treschenko, O. Savostyuk and B. Uspensky, labored unknown or unsung, working under difficult conditions, using stencils and linotype to facilitate the speed of output to capture up to date news. These posters were widely distributed, flowing far beyond Moscow to the provinces, where there would be plastered in the windows of the local Telegraph Agency. The massive numbers and expansive distribution of these perishable art forms should be contrasted with the work of artists in Moscow, where photomontages by Alexandre Rodchenko and posters by El Lissitzky tended to remain in more or less elitist circles. The ROSTA posters were kin to the propaganda deployed during the Great War and cousins to the peasant art form , the lubok, but it is important to note that these posters were far less complex and were far more eloquent in their new stripped down easily readable language. According to Alexander Roob, writing in 2914 for the Melton Prior Institute,

The project was support with great effort by Platon Kerzhentsev, the new director of ROSTA. Kerzhentsev was one of the driving forces of the avant-garde Proletkult organization, whose aim was to establish an autonomous working-class culture leaving all traditional, bourgeois genres behind. The revolutionizing of expression, which Proletkult had hitherto sought mainly in the field of literature and theatre, could now be applied under the aegis of Mayakovsky to the area of graphic picture publishing as well. Mayakovsky selected the ROSTA news items and prepared them along with other poets and journalists for pictorial realisation.

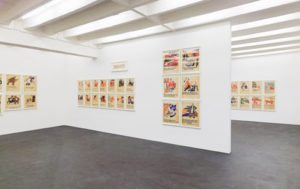

ROSTA posters

Robb noted that “the pictorial sign system” that was developed to reach the “mostly illiterate population” had to be “consistent.” He stated that “The grammar of pictograms established by the ROSTA collective over time is a novelty in the history of illustration. it had a decisive impact on the development of infographics.” Surprisingly, the ROSTA windows (Okna ROSTA) were filled with posters that were designed by artists educated in the most elite and avant-garde of circles and they combined the lubok with Futurism and Cubism with touches of Suprematism that laced these twentieth century comic strips with Western style. The accomplishment of these artists is that the texts engaged the reader in a dialogue that ran parallel to the attention grabbing bright colors and strong shapes. In fact the images in the posters were considered ideograms or hieroglyphs, picture writing accompanied with reinforcing texts that gave instructions on how to survive in terrible times. The posters told entertaining and sometimes horrible stories containing information with entertainment and were among the best examples of art being put into “production,’ in other words, art taken out of the artist studio, out of the galleries and out of the museums and placed in the middle of life itself, an ongoing historical situation that was changing by the hour.

Exhibition of ROSTA posters

Mayakovsky stated, “Art must not be concentrated in dead shrines called museums. It must be spread everywhere–on the streets, in the trams, factories, workshops and in workers’ homes.” Instead of heavy handed critique, satire from artists Victor Deni, was used to discredit the Whites and those who disagreed with Communism. The major achievement of the ROSTA posters was that of creating an efficient sign language, uniquely suited to the pouchier style of drawing and print production. Rushed from town to village by rail, the poster artists devised but a visual and verbal language which was able to communicate effectively with peasants without patronizing them. The tradition of the ROSTA posters came to an end with the Civil War and, under Stalin, this very bold and efficient mode of communication fell by the wayside to make way for a more traditionally illustrative tradition coupled with simple slogans. But in their day, the importance of the ROSTA posters and the vital role they played during the war is reflected in the warning: “Anyone who tears down or covers up this poster – is committing a counter-revolutionary act“

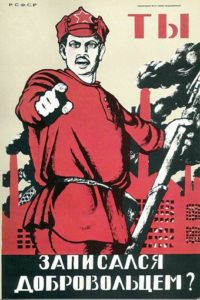

Dmity Moor. Have You Enlisted In the Army?

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.