Sir David Muirhead Bone (1876-1953)

The First Official War Artist

It is one of the ironies of British military history that Wellington House decided to take two steps that would change the way in which the Great War was depicted for the public in the fateful summer of 1916. This is the summer of the Somme, perhaps, for the British, the most famous battle of the war, an engagement which gave rise to the idea that the high command cravenly and ignorantly and stubbornly led hundreds and thousands of young meant to their deaths, deaths for the sake of a few years of blasted soil. Of course Wellington House, in charge of a modern propagandizing of a modern art, had no way of knowing what the summer of 1916 would do the the citizens of the United Kingdom when it appointed Muirhead Bone, an otherwise respectable if undistinguished artist, as its first Official War Artist. Most remarkably, the War Propaganda Bureau also decided to do something remarkable and unprecedented–to make a film of the Battle of the Somme. Once again, the Bureau could have not known that the first day of the Battle, July 1st, would be the bloodiest day of the War, tens of thousands of young men ending by the end of the day.

Muirhead Bone at the Somme

The Somme was the site of the “Great Offensive,” long planned by the French, but interrupted by the unexpected German attack on Verdun. Georges Braque was on this part of the Front, Matisse’s mother was caught in a German-occupied town in Picardie, and the battle of the Somme, like that of Verdun, lasted long enough to allow many war artist, most of whom were “official,” to survey what rapidly became a ruined bombed out landscape. For a traditional artist, such as Muirhead Bone, the lack of “scenery” was disconcerting. In this flat terrain, relieved here and there by a slight hill, human habitation would be shelled from miles away by huge guns–French and German–artillery heard but not seen. The procedure, repeated over and over despite repeated failures, was to bomb the trenches of the enemy for, not hours but days, in the belief that the inhabitants of the trenches would be killed.

Muirhead Bone. Battle of the Somme (1916)

However, although they might be deafened and stunned, even driven mad, the soldiers usually survived the bombardment. They could rise up, drag out the machine guns and destroy the advancing troops. For the artist, the sight before him resembled the dark side of the moon, pocked with craters, filled with water, glinting in the summer sun, the earth itself, made of sticky clay, heaved with dead bodies, some buried, sone not. In such a landscape, the people, who usually were placed in a landscape, were hiding below ground, and the artist looked out over a blank field of destruction. In his article, “Why Paint War? British and Belgium Artists in World War One,” Paul Gough wrote,

A distinguished Scottish etcher more used to drawing industrial and architectural scenes than distant battlefields, Bone was nicknamed the ‘London Piranesi’ for his ability to depict vast and complex construction sites, shipyards, cathedrals and docksides.[1] Nothing daunted him. But on the static battlefields of the Western Front he struggled to locate the face of modern war; it was elusive, distant and nocturnal. By daylight, the battlefield, or what he could safely see of it, was empty and deserted, with tens of thousands of combatants secreted in the trenches or hidden far behind the lines. At night it was crowded with activity but too dark to draw. Like the few official photographers who had been sent before him, he became frustrated at the huge scale of the war on the Western Front..

The official photographer of the Australian imperial Forces during the Great War, Frank Hurley (1885-1962), “the mad photographer,” found the bleakness of the battlefields of Flanders to be extremely difficult to photograph. He described “Figures scattered, atmosphere dense with haze and smoke – shells that would simply not burst when required. All the elements of a picture were there, could they but be brought together and condensed”. Hurley who had accompanied Shackleton to the Antarctica turned to composite photography to inject some conventional composition into what would otherwise be an image with few features other than dead bodies. The artist and the photographer alike were defeated by the reality of modern war. Keeping in mind that the worst battle of the War was going on while he was sketching, Bone, a true professional, worked quickly in pencil, pen, charcoal and soft chalk, and he functioned efficiently on the ground and in a period of a mere six weeks produced one hundred fifty drawings. It took a fair amount of courage to keep one’s cool and to keep drawing while the British troops were under attack.

Muirhead Bone. Battlefield at the Somme

As one of the soldiers who witnessed Bone working recalled, “It was heroic of him to bring out his sketch book and make rapid notes of the scene around him. Once when a shell burst near him his pencil went clean through his paper, but he carried on while our men were taking cover under bits of wall, and wounded were being carried off.” When his work appeared courtesy of a somewhat unlikely sponsor, Country Life, acing for the Authority of the War Office, published catalogues of The Western Front. Drawings by Muirhead Bone, available for the interested public. Published in a ten part series, each section selling for two shillings, the segments sold some 30,000 copies. In writing the article, “A century of war art that began with Muirhead Bone,” BBC quoted the author of the 2014 book, A Chasm in Time, Patricia Andrew, who said of the artist, explaining his struggles, “It was always a sea of mud, shattered trees, shattered buildings, and it all looked rather the same..If you look at his pictures of the Western Front, they’re not the best examples of his work..He’s struggling to make some sort of individuality in pictures that are just mud, trees that are shattered, houses that are shattered, the odd chateau that is shattered. It’s a bit samey.”

In comparison to his rather dull drawings of day to day life on the front, Bone’s writing could be more vivid. In The Western Front, he described the Somme in these words:

Many skilled writers have tried to describe the aghast look of these fields where the battle had passed over them. But every new visitor says the same thing—that they had not succeeded; no eloquence has yet conveyed the disquieting strangeness of the portent. You can enumerate many ugly and queer freaks of the destroying powers—the villages not only planed off the face of the earth but rooted out of it, house by house, like bits of old teeth; the thin brakes of black stumps that used to be woods, the old graveyards wrecked like kicked ant-heaps, the tilth so disembowelled by shells that most of the good upper mould created by centuries of the work of worms and men is buried out of sight and the unwrought primeval subsoil lies on the top; the sowing of the whole ground with a new kind of dragon’s teeth—unexploded shells that the plough may yet detonate, and bombs that may let themselves off if their safety pins rust away sooner than the springs within. But no piling up of sinister detail can express the sombre and malign quality of the battlefield landscape as a whole. “It makes a goblin of the sun”—or it might if it were not peopled in every part with beings so reassuringly and engagingly human, sane and reconstructive as British soldiers.

The introduction to the Drawings was written by Field Marshal Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, an extremely controversial general, who was in charge of the offensive at the Somme, and less controversially, a fellow Scotsman. But the controversy over Haig’s role in the slaughter emerged after 1917 and was based upon a few lines from the memories of his counterpart at the Somme, Erich Georg Anton Sebastian von Falkenhayn (1861-1922) who wrote this bit of remembered dialogue between German commanders: Ludendorff: “The English soldiers fight like lions.” Hoffman: “True But don’t we know that they are lions led by donkeys.” This phrase, “Lions led by donkeys,” became applied to Haig, the leading “donkey.” The reputation of Haig has been batted around like a shuttlecock by historians for the past one hundred years, but at the time he wrote the introduction for Bone, the War was still dragging on and his eventual fate was still unknown. Was he “The Butcher of the Somme” or “The Man who Won the War?” In his own time, he was criticized by Winston Churchill for the loss of life on the Somme, where there was “a welter of slaughter.” Churchill also wrote that the general “had sent the flower of British youth to death or mutilation; at Passchendaele he had tipped the survivors in the slough of despond.” Haig, who spend much of the Battle of the Somme convinced that the future of the military was the calvary, went on in 1917 to command at another costly battle at Passchendaele, where there were so many shell holes filled with water that soldiers drowned. But he persisted in his tactics of hurling human beings at machine guns, even though as Churchill said, “Lads of 18 and 19, elderly men up to 45, the last surviving brother, the only son of his mother (and she a widow), the father, the sole support of the family, the weak, the consumptive, the thrice wounded—all must now prepare themselves for the scythe.”

The unbelievable losses at the Somme and Verdun and subsequent battles were the result of a tragic lack of military imagination and unwillingness to come to grips with modernity. As late as 1926, Haig wrote, “I believe that the value of the horse and the opportunity for the horse in the future are likely to be as great as ever. Aeroplanes and tanks are only accessories to the men and the horse, and I feel sure that as time goes on you will find just as much use for the horse—the well-bred horse—as you have ever done in the past.” And yet he seems to have understood the battlefield and the problem that Bone, the first official war artist, faced in trying to explain this new kind of war:

The conditions under which we live in France are so different from those to which people at home are accustomed, that no pen, however skillful, can explain them without the aid of the pencil. The destruction caused by war, the wide areas of devastation, the vast mechanical agencies essential in war, both for transport and the offensive, the masses of supplies required, and the wonderful cheerfulness and indomitable courage of the soldier under varying climatic conditions are worthy subjects for the artist who aims at recording for all time the spirit of the age in which he has lived.

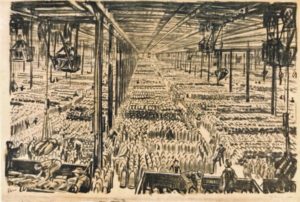

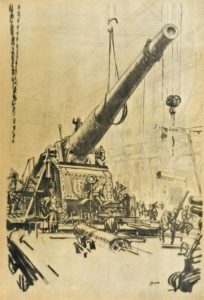

Muirhead Bone. Shells in Munitions Factory (1917)

Despite Haig’s glowing introduction, Bone’s efforts were meet with scorn by art critics and civilians alike. His renditions of the War were simply too realistic and too truthful to be interesting. The public was hungry for images and eagerly attended the exhibition at Sheffield’s Mappin Gallery in 1917 of one hundred of his war prints. However, as Gough recounted, his work was so well-regarded by the Propaganda Bureau that the officials hired more official artists, and thousands of people in Great Britain and America became familiar with the War though his work. In his article, “A War of Imagination?: The Experience of British Artists in Two World Wars,” Paul Gough, wrote,

By his own admission he recognised that modern war was an elusive and remote activity: “I’m afraid that I have not done many ruins … But you must remember that on the Somme nothing is left after such fighting as we have had here – in many cases not a vestige of the village remains, let alone impressive ruins !” Bone drew the aftermath of the fighting, he was rarely allowed near the front-line. As a result his panoramic sketches of the battles of Mametz Wood or the bombardment of Longueval show little more than hazy smoke on a distant horizon. As one critic noted it was “like a peep at the war through the wrong end of the telescope.”

In reviewing The Western Front in 1917, “C. L.” in Volume 31 of The Burlington Magazine, wrote,

Mr. Muirhead Bone has clearly justified the action of H. M. Government is employing him as an official artistic chronicler of the greatest of all wars..Huge as the scale of warfare has been, it has all the same been somewhat featureless, and certainly lacking in picturesque interest. It has therefore been difficult for Mr. Bone to discover and select subjects, which stimulate the creative fancy and produce a picture, which is something more than mere illustrated journalism. The danger of this kind of work lies in the artist being merged in the mere journalist..Huge guns pervade his later work, and much as one may admire Mr. Bone’s technical skill in dealing with such monstrous objects, one may doubt if he has really been able to infuse any artistic interest in them. Guns are inhuman and immobile, devoid of plastic sensibility.

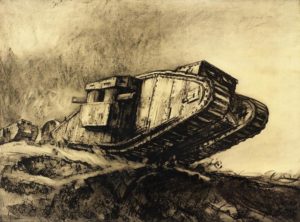

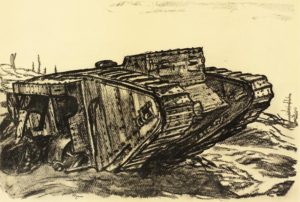

But despite the rather boring accounts put forward by by an artist baffled by his task, his drawings could often be informative and his work with the new weapon, the tank, produced truly iconic images.

Muirhead Bone. Tank (1917)

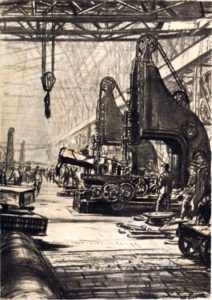

It was here, with the machines, that Bone found his footing. The aesthetic and artistic different between the anemic sketches of the battlefield and the dramatic and strongly felt depictions of the machines that were making a new world is stunning.

From The Western Front: The doors of the furnace have just been thrown back and the heated gun tube is about to be lifted by the giant pincers of the crane.

Suddenly a rather boring and prosaic artist, uninspired by being a witness to the greatest carnage of the twentieth century, closed his eyes and turned away, muted by the slaughter and the suffering. The machines of war were another matter. More than any other artist of the Great War, Bone captured the menace of the guns, the destructive capabilities of modern weapons, the size of these objects of destruction.

Muirhead Bone. Giant Slotters (1917)

He drew the nearly unrecognizable weapons–they were so new–as things of darkness, inventions rising up from hell. Going through The Western Front, is like taking a journey into the heart of the pit of the War and into its pity and pathos as well. Bone never allowed his viewer to see the other side of the guns, the men targeted, the men destroyed, the men who became “the missing” of the Somme.

Muirhead Bone, Mounting a Great Gun (1918)

It was those weapons of mass destruction, depicted by Muirhead Bone, that were utterly fascinating. Perhaps the most vivid image was the lurching and looming tank, thrusting itself into the pitted landscape, nosing its way towards the enemy, symbolizing the new modern war.

Muirhead Bone. A Dead Tank (1918)

Muirhead Bone. A Line of Tanks (1917)

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.