Sir David Muirhead Bone (1876-1953)

The First Official War Artist

The Great War posed unique challenges to artists, especially those born deep in the nineteenth century and trained in its artistic techniques and standards. Mature and distinguished by the time the War began, these artists were, a as a group, constitutionally unable to grasp the meaning of the terminal conflict that was ending the way of life they had known. A younger artist, a man such as Christopher Nevinson or David Bomberg, would have instinctively grasped the import of the War through their personal experiences as soldiers. Their paintings of war, whether Paul Nash’s accounts of the destruction of innocence through nature, were embedded with their personal pain. Older artists, such as John Singer Sargent and his colleague Henry Tonks, were sanguine enough and old enough to look War in its face and not flinch, but they could not react its horrors with the old tools and the old methods. Strikingly, the matured artists did not develop new languages or new methods of expression to the wholly new experiences. And yet these artists, in their familiar styles and their uncritical straightforwardness that masked deeper truths, were public favorites. It was they who educated the British people on the facts of the War, while their younger counterparts revealed the pain of the War. There is a strong visual difference among these “Official Artists,” working for the government. The older artists not only spoke in languages that were now dead but they also were contented with visiting battlefields under safe conditions. The younger men, however, had lived and fought on the trenches, and had tended to wounded and dying soldiers, experiencing war close up and in a very intimate way. Because many, such as Nevinson and Bomberg, were well versed in modern art languages, they were able to deploy these dialects to visually convey the war and its bleak and terrifying costs. It is interesting to note that, in the case of Nevinson’s Paths of Glory, censorship from the very government that had hired him struck when the artist shifted into realism.

Conflicting and conflicted generations, these artists worked in tandem with the famous Wellington House, the propaganda arm of the government. The goal of Wellington House, an early form of an intelligence unit, was not to inform as much as to educate and convince neutral nations, such as America, of the importance of joining Great Britain and its allies in the Great War. Given that the goal was to make clear the necessity of American participation, Wellington House and its distinguished roster of writers, such as Rudyard Kipling, the discussion of the War was focused upon the vileness of the Germans and the urgency of defeating the aggressive and ruthless foe. Naturally, given the immediate evidence of how horrible this War was, Wellington House was somewhat hesitant to include visual artists in this enterprise but the government agency, under the leadership of Charles Masterman, began to hire photographers and then a well known printmaker, Muirhead Bone to convey the official British position on the war. As M. L. Sanders explained in the article “Wellington House and British Propaganda During the First World War,”

At the outbreak of war in August 1914, the Germans poured out propaganda in the form of posters, leaflets and pamphlets, in an attempt to explain Germany’s entry into the war and discredit the motives of the allies. The British government was greatly disturbed by the virulence of he German campaign, which was specifically directed towards influencing then United States of America..On 5 September the cabinet decided hat steps were to be taken without delay to counteract the dissemination by Germany of false news abroad. Though there had been no peace-time precedent, the cabinet accepted the need for an organization to co-ordiante propaganda directed at foreign opinion for the duration of the war.

Visual artists, however, were invited into the “official” propaganda ranks once the government realized that photography might not be the best tool for reaching the public. In what is surely, if not the first, one of the first books on the artists during the Great War, Albert Eugene Gallatin in his 1919 book, Art and the Great War, wrote, “..as far as its known, the Great War was the first to be officially recorded by artists. This innovation is one that the historian and posterity will certainly welcome, for pictures, far more adequately than the written word, were capable of recording the great conflict.” Gallatin noted “The hideousness and horror of modern trench warfare is also far removed from the pageantry and splendor of warfare in the Middle ages–it is vastly different from the comparatively picturesque and open warfare of the Napoleonic epoch. War pictures of today have almost no roots in the past; the pictorial recorder of modern warfare has had lost no sign posts to guide him. For one thing for the first time landscape formed an important feature of the war picture.”

What Gallatin stressed, early in his book, was the way in which landscape became, in effect, the image of the war. Paul Nash agonized over the destruction of the countryside of northern France and southern Belgium. Trenches had to be lined with duckboard walkways and the walls had to be shored up with timbers, and, as in the days of the cathedrals, the forests were denuded to “build” the endless zig-zag ditches. What deforestation began, shelling finished and one of the key features of the paintings of the war, one of the salient symbols for death, was the tree, shorn of branches and leaves, cut down, left as a splintered spike, a ghost stalking the ruined land. Traditional military painting had used landscape as a backdrop to a theatrical presentation of dashing action scenes, but this new war presented no such opportunities. A calvary charge was an invitation to instant death and became extinct; a neat march towards to enemy ranks was a recipe for mass murder. The soldiers stayed below ground, like moles, unless they were ordered to climb the ladder and go “over the top.”

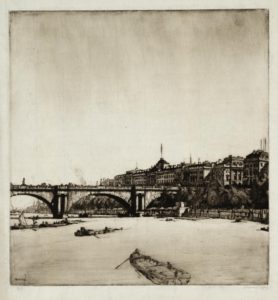

In 1908, Muirhead Bone was famous enough to warrant what amounted to a catalogue raisonné of his prints, authored by Campbell Dodgson. Bone, a Scottish artist, was trained as an architectural artist and specialized in views, sometimes landscapes but for the most part of architectural sites. In many ways his etchings and drawings were reminiscent of the photographs of Charles Melville in Paris in which the photographer recorded the demolition and rebuilding of Paris. In making this comparison, one also notes the nineteenth century aspect of his art. He was skilled and talented and an excellent observer of views, and one can follow the thinking of Wellington House in the selection of such an uncontroversial artist who would was qualified and who could be counted on to follow the instructions of the propaganda office.

Sir Muirhead Bone. Ballentrae School House (1905-07)

Sir Muirhead Bone. Snowy Morning, Queen Margaret’s College, Glasgow (1901)

In the Spring of 1916 at age thirty-eight the printmaker was faced with being called up for active service, a sign that England was reaching deep into its male population after the huge losses of 1914 and 1915. The year of 1916 was the year of the Battle of the Somme, folded simultaneously. into the Battle of Verdun, a continuous engagement. Fought from February 21st to the 18th of December, Verdun was the longest battle of the War, lasting almost a year. The Battle of the Somme itself, began on July 1st and continued until November of that year. Faced with the prospect of active duty on the Western Front, Bone was luck enough to have a literary agent, A. P. Watt, suggested to the director of Wellington House, Masterman, that it would be wise to utilize the artist, not as a soldier, but as an illustrator of the war. According to Lucy Harris in her article, “Sir Muirhead Bone: A Great Recorder of War,” and Lucy Stamp suggested that another artist, William Rothenstein, also recommended Bone. It was at that point that the government decided to create “official” artists to record the war. And so in May of 1916, Bone became the first official British artist, just in time to record the worst battles of the war, giving the conflict, according to the demands of propaganda, some “realism.” The artist who had never been out of England went to the Western Front, or what the Germans called die Westfront” and the French called “Le Front Occidental,” arriving in August at the peak of the fighting season on the Somme. At first glance, his architectural training would make Bone an ideal artist for explaining, through his prints, the structures of this modern war, but when his body of work done at the Somme was officially presented to the public in 1917, the response was mixed at best.

Sir Muirhead Bone. Somerset House (1905)

Sir Muirhead Bone. Study for the Great Gantry at Charing Cross Station (1906)

In order to understand the somewhat muted reception of the drawings Sir Muirhead Bone produced during his visit to the Front, it is necessary to briefly outline the conditions of the Somme during the prolonged battle, named after a river the name of which means “tranquil.” In writing of this battle Joshua Levine in Forgotten Voices of the Somme: The Most Devastating Battle of the Great War in the Words of Those Who Survived reminded the reader that “Its first day was the army’s bloodiest, and the total of 415,000 British causalities–to which must be added the 200,000 French and upward of 600,000 German–make it one of the deadliest battles in world history.” The death toll, for the British, was particularly painful. Unlike France, England did not have the “draft,” and its Army, small and professional, had been designed to defend the Empire. The United Kingdom, an island kingdom, relied upon the superiority of its Navy to defend it, and when the War proved to be mainly a conflict over a line that that the Germans had pushed into French territory, it was necessary to raise a volunteer army. Through a campaign of posters which will be discussed in other posts, the government raised an army composed of friends and family, inhabitants of towns and villages, school friends and cousins. These “Territorials” or part time soldiers, men of the Empire would be composed of units who knew each other. The result of the idea of having people who were either socially or biologically related would be neighborhoods left without males and mothers, sisters, and wives left without their loved ones. Levine quoted from a letter by Private Donald Cameron from Sheffield discussing the make up of one of these local battalions:

Our Pals battalion was formed as the result of an appeal from the Mayor or Sheffield, Lieutenant Colonel Branson..University students, doctors, dentists, opticians, solicitors, accountants, bank officials, works directors, shop owners, town hall staff, post office staff, you name it. Professional men, not professional soldiers, but when they got in the trenches, they behaved like professional soldiers.

The letter reminds American readers of the army the United States sent to Europe during the first and second World War–a citizen army. In explaining the significance of such a military, in his book, The First Day on the Somme: 1 July 1916, Martin Middlebrook explained that the first army the British sent over, the BEF, British Expeditionary Force or the Regular Army had been all but wiped out by the end of 1914. The war continued on the Front, with the French in the lead and the British as support in Europe. But in 1915, the Empire attempted a flanking movement against Germany and its allies via Gallipoli, at attempt which wiped out a large ANZAC invasion force. The situation on the Front only became more desperate and the need to end a war of attrition was acute on both sides. It should be noted that the Germans dug into French territory and had no intention of being pushed back. Their trenches were far superior to those of the French or the British, which were assumed–optimistically–to be temporary. The French, whose losses had exceeded the British, could not give up their country and surrender. In the summer of 1916, aided by the fact that the French ignored warnings about enemy movements, the Germans attacked at a weak spot on the French lines, Verdun. Attacks along this part of the Front, assaults and counter assaults repeatedly continued for almost a year in what was a deliberate attempt to “bleed” France to death. In fact the subsequent Allied offensive along the Somme was an attempt to relieve the pressure at Verdun. The lack of progress in battle after battle, the lack of decisive victory against the Germans made the feeling of irreparable loss all the more acute in Great Britain. One can imagine the impact of Sheffield’s loss of so much of its middle class upon the city itself, so great were the causalities on the Somme.

As Middlebrook expressed it, “Each fresh effort was more demanding than the last, the scale of troop involvement, artillery preparation and eventual failure, went remorselessly up. The more ambitious an attack, the heavier the cost. 1915 was a year of complete victory for defense; a combination of machine-guns, barbed wire, and artillery defied all offensive moves.” The British forces were replacements, barely trained–a condition that would surely add to the losses–but they now had to assume the burden of drawing the Germans away from their relentless pounding of Verdun and make them turn to the Somme. Led by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig had been order by Lord Kirchner to organize the BEF to carry its own weight and to become an equal partner in the fight. In their book on The Somme, Peter Hart and Nigel Steel explained the situation: “The Battle of Verdun was an extreme trial for the French Army forcing them to commit most of their available reserves to the battle. It became apparent that it would be grossly unrealistic for the French to play their originally intended lead role in the joint offensive on the Somme. Indeed the stain was such that Joffre came to see the Somme offensive less as a part of the main Allied assault on Germany and more of a way of relieving pressure piling up at Verdun. The French could still make a contribution to the offensive but it was inevitably scaled down to leave the British Army bearing the brunt of the battle.” When the attack was launched, as the authors put it, “The British were about to fight their first real Continental battle in modern war against the main enemy on the decisive front.”

It is amazing that that War had gone on for two years mainly on the backs of the French, but when the British rode to the rescue, so to speak, the results of the first day, July 1, of the Battle of the Somme were historically disastrous. As the authors wrote, “The cost had been horrendous. In one short day the British Army suffered a massive 57,470 causalities of which a staggering 19,240 were dead. This was the worst disaster ever to have fallen the British Army in its entire history. The county regimental system the British further exaggerated the impact of the casualties. Battalions drawn from a single city area, or a provincial town were alighted and whole communities were thrown into mourning.” The authors then quoted from an account of a woman who had been a child in wartime Sheffield, “The city was really shrouded in gloom. They were very, very sad and nothing seemed to matter any more.” To put the casualties in perspective, those numbers almost equal the total death toll of Americans during the years long Viet Nam War. It was into this landscape, during the preparations for the Somme that Muirhead Bone arrived in France in August of 1916, a month after that horrible first day. It was his task to put a brave face on the British presence on the Somme.

The next post will discuss the efforts of Sir Muirhead Bone, the first official artist on the Western Front, and how he chose to depict the Great War.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.