Painting While Black

Métissage as Biomythography

Launch Gallery

170 S. La Brea Boulevard Los Angeles

Summer 2018

Holly Tempo, James Panozzo of Launch Gallery, and Loren Holland

Holly Tempo

Of Unknown Value

For the artist, Holly Tempo, the question becomes what does “difference” mean in the twenty-first century? A century not yet twenty years old has been whipsawed between a premature post-racialism and an unexpected return to the very same segregated times that shaped the philosopher Édouard Glissant and writer Audra Lorde. To speak in this unexpectedly racialized decade is to live dangerously with “difference.” This postmodern difference has been reshaped through a radical reweaving by twenty-first-century voices. Writing for Documenta 11 in the year 2000, Okwui Enwezor meditated on globalization in the new century. He noted that the concept is “constantly brought into the phenomenological orbits of spatiality and temporality in order to be disciplined inside the cold logic of the mathematical analysis of capital production and accumulation, and economic rationalization. Another point about globalization gives rise to the thought that its cumulative effects and processes are to be understood as mediations and representations of spatiality and temporality: globalization is said to abolish great distances, while temporality is best experienced as uneven..From the moment the postcolonial enters into the space/time of global calculations and the effects they imposed on modern subjectivity, we are confronted not only with the asymmetry and limitations of globalism’s materialist assumptions but also with the terrible nearness of distant places that global logic sought to abolish and bring into one domain of deterritorialized rule.” This famous essay, “What is an Avant-Garde Today? The Postcolonial Aftermath of Globalization and the Terrible Nearness of Distant Places,” and the landmark Documenta 11, which placed the curator and poet and his voice in the forefront of the arts. Enwezor was grappling with the sudden compression of space and time or different modes of engaging with or grappling with space through the lens of shifting perceptions.

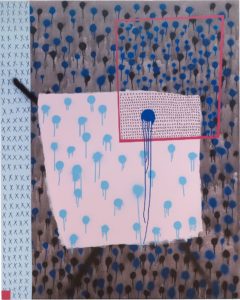

Holly Tempo. Red Black and Blue (2018)

Enwezor’s essay suggested that artists had to reconsider this change to topography, which has become folded in upon itself. The abstract paintings of Holly Tempo take the viewer on an extended walk through this subtle and new “difference,” which is to be multiplied and embraced and understood through Enwezor’s contemporary explaining of the fungibility of global time and space. If there is no longer a fixed point in space for us to cling to, then we are wanderers and mapmaking becomes an act of métissage. Without Eurocentricism to rule the world map, placing Europe at the center of the world, then the fixed point is space is lost, and, when the chart of the world is evened out, the equality of parcels is acknowledged, and time is compressed. Tempo’s paintings acknowledge and play with the layering of time and space. Segments seem to pile one upon the other and then disgorge themselves towards the viewer, unsteady marks dancing across a crowded field, jostling one another in their haste to find their place in the allotted space via métissage.

Tempo presents a new assertion of linguistic topography, described in Antinomies of Art and Culture: Modernity, Postmodernity, Contemporaneity, “Topography could be a form of writing that provokes the imaginary and evokes the real sensation of art and landscape. The aim of topography is not to recount stories of previous adventures; it is more concerned with the tracks and traces that are still visible and portable. Topography is also concerned with the mapping of invented signs that have no genealogical reference but rather a phantasmagorical relationship to place. The origin of signs can be endless and melancholic. To break from this regress, topography focuses on what happens when small gestures are made in a specific place.”

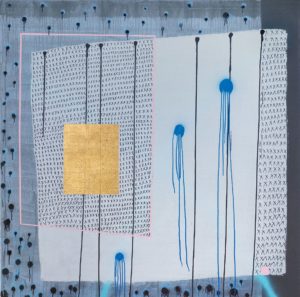

Holly Tempo. Of Unknown Value 2 (2018)

The title piece her exhibition at Launch gallery does not attempt to relate stories of her home, Inglewood, for the fate of Inglewood, the “‘Hood,” was sealed through Hollywood intervention. Once certain spaces are defined as off limits, as places to be patrolled and contained and commanded but not visited, they become, like Inglewood, of “unknown value.” “Unknown” to whom? Does this value refer to its commercial value? Or to the future of the part of the city that was pushed to the fringes? Inglewood is just such an in-between place that is unsteadily sliding between danger and safety, and is haunted by what the artist terms “what ifs?” What if a victim of gang violence had stayed home? What if a gang member had stayed in school? What if the neighborhood had not been cordoned off by the reputation of its main street, “Florence,” made famous after the 1992 incident at “Florence and Normandie?” Walking through myth, silenced stories, retrieved memories, Tempo is a flâneuse in a district that, as she says, “traverses a variety of communities that range from severely impoverished to wealthy..” She speaks of the “world of contradictions” in a place troubled by upheaval and change as gentrification pushes into vulnerable spaces. As she explores, walking from block to block, she finds “graffiti, discarded furniture and other trash, untended parkways and sidewalks, stray dogs and cats. Also to be found, are beautifully maintained yards, lovely bungalows, quality restaurants, kids playing, trees and birds.” These disadvantaged and marginalized squares in Los Angeles conceal what the artist calls “cultural history, psychological trauma, and social anger.” but she chooses to not reveal the embedded stories. Instead, she gestures towards the buried histories through a braiding of linguistics in painted actions constituting a postmodern métissage.

Holly Tempo. RIP Javier (2015)

Tempo deliberately and consciously deploys the global language of international art which transcends time and space to reference very specific incidents in a marked site. By freeing the individual marks from their original purposes and allowing the liberated character to assume a life on its own, she uses these characters like hieroglyphs, non-pictures that are overcome with entangled meanings. Like RIP Javier, Blue Abatement is a memorial, found, by the artist, as she moved through gang territory. There are two rival gangs, generations old, with their legacies of membership, the Crips and the Bloods, the blue and red signals, signifying membership and marking individuals as belonging to a place. Tempo’s blue tones of her palette are always braced with an underlying red and the red is always tempered with touches of blue. These mixed and alloyed colors are her strands that she picks up and carefully braids into a fabric, which in Inglewood, always threatens to unravel. Conversely, the very nature of being in a gang is to be in a state of instability, part of a volatile group and yet coming from a fixed biological family and belonging to a very specific turf. Inglewood is in the process of transitioning out of its own supposed blight and is being transformed into an upwardly mobile built environment. Soon capitalism will turn the streets inside out and wipe out the memories of this liminal space, whitewashing the street texts into a final muting. Tempo is collecting the traces of this fleeting topography of abatement before its inevitable erasure. But one would be mistaken to think that Tempo is writing a history of social dysfunction. Her work is far too subtle for the obvious and the artist abruptly changes languages and the marks metamorphosize into another form of speech.

Holly Tempo. Blue Abatement (2018)

Tempo’s paintings refuse to stay still and will not allow themselves to be read from one perspective. Each linguistic tool, brush or spray can, pen or marker, can turn its face and speak in another dialect. The strictly controlled and carefully positioned painted layers, which for the artist, include the space of time–the watching, the waiting, are the processes of looking that is part of the artistic process of thinking. Each element is joined by other forms all of which are carefully woven with looped meanings, one superimposed upon the other. The different textures of the strands Tempo decided to articulate are spoken through the tools of artmaking that turn objects in images and pigment on canvas into nuances, gesturing towards shadows. The spray paint with which she shoots the helpless canvases may indicate graffiti or bullet holes, an aggressive tagging or a bleeding on the sidewalks. The bursts of spray seem to bloom and grow like a field of flowers and the crosses become an assertion of presence canceling out the suggestions of death but they can also be death itself. The carefully masked and measured frames that appear inside the painting suggest that someone has trespassed into alien territory but the creation of domains is a technique that owes much to Frank Stella. Within this protected and bounded space, divided up with tape, Tempo draws Xs to count the killings–the drive-by shootings, the stabbings, the beatings, the overdoses–with a prim magic marker, the official instrument of counting the casualties.

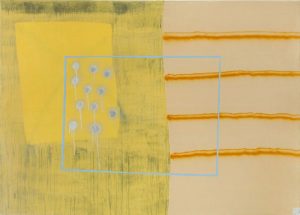

Holly Tempo. Of Unknown Value 9 (2018)

The artist pillages art history and paints carefully in stages as she adds layers, selecting tactics from “the formal language of painting (drips, hard-edge bands, the color field, compositional elements) with tropes from urban environments (spray paint, graffiti marks, abatement gestures, gang colors, and the ever-shifting line as defined by building, power-line, fence, or even state of mind)” to express the métissage of the complex topography. This sense of place, which Tempo daily discovers, is mapped out with squares of gold leaf which act as seals over the surface as if to announce a completion or a polishing of the facture, a final nod to a Byzantine tessera. All of these gestures are the tools of the master. Tempo takes over these systems of handwriting and transforms them. In Red, Black, and Blue, the staccato bursts of sprayed paint develop a new morphology, gather together in clusters that suggest Ross Bleckner’s falling birds have become a field of blooms of blue. These references, such as the flag-like suggestiveness of Yellow Abatement, recalling a waxed flag from Jasper Johns, are a very deliberate strategy of quotation on the part of the artist.

Holly Temp. Yellow Abatement (2018)

When Holly Tempo emerged from graduate school over twenty years ago, women were just beginning to taste, ever so slightly, some of the rewards of the art world. But the women who were becoming accepted into the inner critical circles, the prominent galleries, the homes of important collectors, were often in new fields and disciplines, such as photography, video, and installation art. These new multimedia areas were not already occupied by the men of the art world. Hence, if success for women was problematic, at least access to the art world was open for Cindy Sherman, Barbara Kruger, Sam Taylor-Wood, and Rebecca Horn who found a place to stand that was relatively unoccupied. However, the aesthetic field held triumphantly by males was painting, which, despite the challenges of Conceptual Art, held firm to its position as the blue-chip star of the art world. For women to confront this carefully guarded arena, the preserve of males, was a daunting prospect. After centuries of being marginalized in the minor leagues of craft, they had no authentic visual language that would allow them to paint with authenticity. As a woman of color, living in a community “othered” by the minority majority of Los Angeles, Tempo faced this apparent lack with determination, borrowing, stealing, appropriating the alphabet of men, the marks and strokes, the techniques and the panache, she took them all. Seizing the highest summit, abstract painting, she takes the historical and gendered language between her hands, mashes up the syntaxes, and releases them as new words for the woven world of hybridities.

Holly Tempo. Of Unknown Value 6 (2018)

In making a transition between the discussion of the two artists, Holly Tempo and Loren Holland, it is helpful to bring to the fore the philosophical role of the inscription “X,” the device of sous rature. Tempo uses the X to challenge the prevailing cultural judgment that graffiti is vandalism and not art, and, hence, is not “culture” but crime. Writing on the walls and in the streets is and has been a time-honored and valid mode of communication and can be a highly effective means of making art. Rap, rather than being recognized as a form of spoken word poetry, is often considered to be an inciting form of speech by those who are outside the precincts of black life in America. Clearly, the use of the word “culture” which has been tainted by colonialist assumptions that cast negative shadows upon the art of the Other, labeling rap and graffiti as “outlaw” rather than as serious statements of protest. This loaded term, “culture,” must be put sous rature, crossed out and yet retained in order to hold the multiple terms together and allow them to proliferate. The postcolonial artist must understand that she is writing a type of archi-écriture, which is also écriture, at the same time, writing. The borrowed marks are deployed not to represent but to serve as a figure, a shadow of that which is normally suppressed. These artists put culture sous rature, to deconstruct its traces and critique its suppressing mechanisms.

Enter Loren Holland. Using narratives in precisely painted oil paintings deliberately packed with excessive meanings, Holland demonstrates to the viewer what it feels like to be surrounded by social expectations of beauty and decorum based upon a white “culture.” This white culture is then imposed upon black women who must contend with conflicting demands to look and be both “white” and also represent “black.” But the African-American variety of “black” is white-invented, placed like a burden upon the backs of the daughters of slaves. Holland fights the imposition of standards of white women–a certain kind of straight-haired beauty, a particular marital arrangement, a body approved by fashion magazines–on two fronts. Her complex iconography piles up stacks of codes that must be de-naturalized, while, at the same time, Holland invades and rewrites the ancient folk tales and myths upon which white culture is founded. Her task is to retain the hyphen of the hybrid culture she has inherited in order to write a new authenticity in a strong clear voice.

Installation of Paintings by Loren Holland

Holland re-writes myths of ancient Greece but to enter into this pure white field of literature is to tread upon the sacred ground that is white and male and contested. For Holland to not only modernize but also to color and polychrome such a whitened genre as Greek myth through coloring over and into the lines is destabilizing. To feminize these poems of male valor is, in addition, to tempt fate indeed. Like Tempo, Holland has dared to take up the tools of the master, but she has to take these (erased) cultural objects back to the workshop and reforge them. In other words, to interject the female into such a male discourse, the stories must be sung in an entirely different voice, soprano not bass. Philosopher Édouard Glissant’s American counterpart, the American poet and author, Audre Lorde pointed to the necessity of finding a new way to make art when she said, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” A woman who is black cannot speak in the voice of the white man, but is there an identifying and singular voice for her to use? Lorde also thought in terms of weaving and combining genres. In her hybrid book, Zami: A New Spelling of My Name, she wrote, “Zami is ”a Carriacou name for women who work together as friends and lovers,” making Lorde’s flight from white writing, called “biomythography,” a uniquely female and collective form of writing as weaving polyvocal genres. While not uniquely or exclusively lesbian, biomythography, when it was introduced by Lorde in 1982, became an “outlaw” mode of writing due to its defiant métissage. Like Glissant, Lorde was a postmodernist before her time and defied the academic practice of formal or close readings of works of art. She rejected the given conceptual boundaries and the concept of a center so that she could sing in poetry, a multi-parted harmony of a disjointed life story, told as if it was an ode: “To whom do I owe the power behind my voice, what strength I have become, yeasting up like sudden blood from under the bruised skin’s blister?” she asked. Like Glissant, Lorde was from the Caribbean, a colonized person twice displaced into the land of the master. How, without using his tools, could art be made? As Glissant wrote in his book Caribbean Discourse, “As far as we are concerned, history as a consciousness at work and history as lived experience is therefore not the business of historians exclusively. Literature for us will not be divided into genres but will implicate all the perspectives of the human sciences. These inherited categories must not in this matter be an obstacle to a daring new methodology, where it responds to the needs of our situation.” The answer seemed to be to recite without form or rules, using instead layers of multiple meanings and strands of half-remembered histories and re-reading old codes in unanticipated or ambiguous ways. Decades later, as we creep unwillingly into the unwieldy twenty-first century how do we reinterpret the voices of the elders?

Installation of Paintings by Tempo and Holland

Holland is actually engaged in an act of postmodern translation, which cannot be a one-to-one equivalence. The act of translating becomes an activated and performative scene of rewriting through the sly insertion of difference. Alexis Nouss described contemporary translation as a collaboration. “Translation is an ideological and historical notion involving an agent, the translator. As such, it should be linked to contemporary patterns of subjectivity, of which métissage seems the most appropriate. Métissage should not be confused with the mixture, which implies fusion, or with hybridity, which produces a new unit. Rather, it is an assemblage of affiliations and identities which is never fixed once and for all and in which the different parts retain their identity and their history. In a similar way, the translated text exists through its difference from the original, and the original makes known and legitimizes its own existence only in and through translation. Thus an ethics of métissage constitutes a basis for a politics of translation.” Before discussing the methods of Holland, it should be added that métissage should not be thought of as another version of intertextuality. Intertextuality describes how a text is entangled in a matrix of references–we see this action in Tempo’s paintings. Métissage is additive, with each element retaining its outline in a gathering of pluralities. Holland re-enters ancient myth, bringing with her own experiences, memories, and identities, her life or her biography. She then writes into the existing myth, transforming it into a postmodern fable which has destabilized the original text. What happens when a woman of color critiques the whitest body of literature in the Western world? Perhaps Audre Lorde’s “biomythography.”

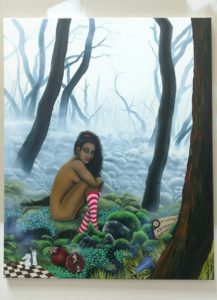

Loren Holland. Shadow Queen (2017)

Myth is a Homeric tale that forges a linear journey in which the female was reduced to an account delivered by a male bard. In the Illiad, Cassandre is doomed to speak truth to those who will not listen. In the Odyssey, Penelope passively waited for her husband while patiently weaving among her suitors. Women have no voice in the hierarchy of Homer. A woman should be wary about the prospect of borrowing the syntax of myth. On the other hand, biography is equally treacherous, implying that one has a home or an origin. Historically, women have been traded among men and lose their names and their tribes and their homes. Women sit uneasily in the houses of strangers. While biomythography implies a combination, the co-joined words imply, in Siamese fashion, two elements that cannot be reconciled. If you are of African origin, you have lost your stories and your songs; they were wrested from you but were allowed to exist in oral traditions of song and verse, disguised as entertainment. If you are of African origin, you have no resting place, you must fabricate and make do, act as a bricoleur and assemble your own narrative. This re-mapping replaces the wanderings of Odysseus who, eventually, found his way to his home, with resignification. Loren Holland took up the inherent and definitional construct of biomythography and combined the lives of black women–biography–with ancient myth and rewriting–graphics–these women into ancient stories.

Installation of the Drawings and Paintings of Loren Holland

with Holly Tempo

Biomythography becomes transformative. But notice that there is no “auto”–the “I” has been eliminated. The “One” has been subsumed into myth and the magic of metamorphosis. One writes one’s own story but also the stories of others in collaboration and togetherness. There is no single author, no solo voice, no authority who presides over a univocal text. This is the outlaw voice that women must find: one that is strong and clear and resists mimicry in favor of inclusiveness. Difference becomes a way of approaching authorship as a reader who writes a self through a defiant braiding that refuses origin or completion. In Shadow Queen, Holland rewrites the legend of Hades and Persephone, often billed as a “love story.” Actually, from a woman’s point of view, this is a frightening story of abduction and rape. Hades, brother of Zeus and god of the underworld, (male)gazed upon Persephone and wanted her. Without bothering with the niceties of courtship, he efficiently caused the ground to open beneath her, dropping her into his territory, the darkness of the underground. One moment she had been picking flowers and the next she was in the clutches of a kidnapper. But Persephone was not without resources. Her mother, Demeter, was the goddess of grain, agriculture, harvest, who presided over summer and spring as well as autumn. Demeter was powerful enough to strike a bargain with Zeus who “allowed” Persephone to emerge from the underworld (winter) to visit with her mother (spring). Holland’s Persephone, naked except for her stockings, shivers, waiting for her mother in the grim and gray confines of the wintery landscape. As the chess board states, she is trapped, there are no moves for her, she is checkmated by her own actions. While waiting for her mother to rescue her, Persephone ate six pomegranate seeds, and, like Eve, was punished for eating. She was forced to return to Hades for six months of the year. The young girl had her own powers, after all she was the daughter of Zeus and Demeter, and was, therefore the niece of Hades. But Greek myths have a way of turning around and punishing women, especially those with power. Demeter must beg for her daughter; Persephone must play the queen of hell for half a year, under the rule of her incestuous uncle. While the ouiji board suggests that she has power to communicate with the dead, her body, shivering and unclothed, as she trembles in the grey gloom of Hell, announces that, in truth, she has no power.

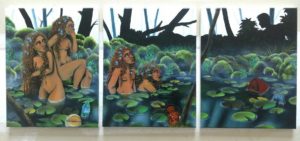

The Shadow Queen, as signified by the pomegranate, is trapped. She is also a woman of color, exposed to interrogation by a hostile white culture that forces her to follow arbitrary rules–six pomegranate seeds–that are both absurd and confining. Unlike more privileged women, Persephone is not allowed to emerge above ground until she has been annually punished forever for her crime of eating six seeds. In her multi-paneled oil painting, The Bathers, Holland selects a myth that refuses to allow the woman to be the victim. At first glance, this painting, with its collection of bathers dipping in and out of a lily pond, is a commentary on Renoir’s Bathers and Monet’s murals of his lily ponds, but the black silhouette of a voyeuristic male in the background cancels out the art history references. In fact, the artist warns us by showing the detritus floating on the surface of the pond: a sliced cantaloupe, a discarded Greek vase, an empty oil drum, marring the serenity of the painting that something is amiss. The disturbance of discards is allegorical, symbolizing the intrusion of humans onto the sacred grounds of nature. In mythic terms, The Bathers is actually the story of Diana and Actaeon, with the whiteness of the nymphs being bronzed, while keeping Actaeon a black shadow as a white hunter. The theme is that of intrusion of humans and their perversities upon the purity of nature and the consequences that followed.

The Bathers is but a prelude to the explosion of revenge that the apparently peaceful wood nymphs will wreak upon the hapless Actaeon. The atavistic need for retaliation that could not be acted out two hundred years ago can be revisited through myth. The best and most cold-blooded telling of “Diana and Actaeon” comes from the classic tale by Thomas Bullfinch. Diana the Huntress saw the spy and reached for her arrows so she could shoot him, but her bow and quiver had been set aside. Outraged that Actaeon had seen her naked “..she dashed the water into the face of the intruder, adding these words: ‘Now go and tell, if you can, that you have seen Diana unapparelled.’ Immediately a pair of branching stag’s horns grew out of his head, his neck gained in length, his ears grew sharp-pointed, his hands became feet, his arms long legs, his body was covered with a hairy spotted hide. Fear took the place of his former boldness, and the hero fled. He could not but admire his own speed; but when he saw his horns in the water, “Ah, wretched me!” he would have said, but no sound followed the effort. He groaned, and tears flowed down the face which had taken the place of his own. Yet his consciousness remained.”

Loren Holland. The Bathers (2017)

The rest of the story is horrible: punished for his male gaze Actaeon is set upon by his own dogs and is ripped to pieces. The antiseptic words of Bullfinch told of the pack of dogs “..all around him, rending and tearing; and it was not till they had torn his life out that the anger of Diana was satisfied.” Hiding, like Actaeon, at the edge of the forest pool, beneath the exquisitely painted set of panels is a submerged subtext of anger, the anger of women who historically have had no recourse against powerful men who have abused them. The original myth or story by Ovid can be found in his Metamorphoses and suggests that Actaeon was an innocent young man who blundered into an embarrassing situation with a woman who overreacted. From the standpoint of biomythography, two stories clash in the night: a revenge fantasy for righteously angry women, whether the daughters of slaves or the members of the #MeToo movement or a warning from history that women are too dangerous and too unstable to be trusted. Holland’s paintings add another level of complexity when she illustrates the expectations that society lays upon women like a stifling blanket. It is no accident that she shows the surprised wood nymphs in the act of bathing peacefully. They have just glimpsed Actaeon in the act of spying, but the final tragedy is off-screen, in a future frame or to be retold in another panel. The viewer is left to wonder about the ending and whether the artist intends a future re-write or an overwriting in a work that has still to be determined.

The position of women is always relative, never is her place independent. She is forever being measured against the male and her fate has always included the male. She is expected to subdue her reservations and incorporate the language of the men who contain her. For eons, unless one was the vengeful goddess, Diana, women were expected to live behind the silhouetted shadows of the men who watched them. However, in the twenty-first century, the role of wife has become problematic. Marriage is promised to be the Happy Ending women supposedly yearn for. It is here, in many a fairy tale, that the story ends: with marriage. The woman leaves her own life and enters into that of her husband, and lives, as the fairy tales repeat, happily ever after. The ancient myth, Primavera, which appears to be a genuine love story, also comes from Ovid in his poem Fasti. The story of a woman is told, once again from a male point of view, and the narrative begins with a male, Zephyrus the God of the West Wind, kissing the nymph, Chloris. Chloris immediately changes into Flora the goddess of Spring, or “Primavera” and Botticelli depicted her as crowned by garlands and surrounded by blooms and blossoms that appear to emanate from her. However, most accounts and paintings of this event leave out an important element: Chloris was abducted and raped by Zephyrus. The loss of her name, Chloris, therefore is the loss of her innocence, and her new name and her new fecundity signify the violent intervention of the male. This darkness is usually banished in favor of painting over the kidnapping and transforming a criminal act into a love story. But in Fasti, the narrator is Flora herself. Now the wife of the God of the Wind and a goddess in her own right, Ovid allows her to speak or provides her with a male-directed voice which describes the blessings and rewards that are bestowed upon women who become reconciled to their fate and submit to male attacks. In ancient writings, there are many rapes and abductions, such as The Sabines, in which the women intervene on the behalf of their rapists, a transparent trope which men write for themselves and at women, teaching women to justify their own victimizations.

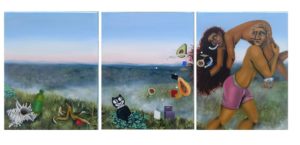

Loren Holland. Primavera (2018)

The contemporary Primavera, painted mid-abduction by Holland, shows the modern woman, trapped between social expectations and their desire for their own independent lives. The lovely young woman, Chloris is in the process of being transformed into Flora as she is carried off by Zephyrus. Buds burst out of her surprised mouth and bloom into flowers, but she leaves behind in her wake, her independence and the way of life that made her happy. Rather than emitting flowers of happiness, this modern Flora vomits away her own sexuality from her lips. Her conqueror has an engagement ring in a Tiffany box to bestow upon her, payment for her surrender. In a postmodern retelling, Holland’s Primavera suggests that men are accessories, deemed necessary for women who must deny their own pleasures in order to satisfy the dictates of society–get married, fulfill the social destiny that has been written for you. But, as The Pact illustrates, marriage is hard. In these two paintings, the uneasy relationship between men and women is explored and modern love is revealed to be a joint enterprise of compromise. Holland is a narrator who uses telling details to draw in and engage the viewers. The Pact is the most modern and least mythological of Holland’s biomythographies. Marriage or relationships between men and women are fraught and, in this painting, both are underdressed, in night clothes, to underline their vulnerability to each other. The artist emphasizes the fact that a modern marriage, much like its ancient counterpart, is a financial and economic enterprise, using an adding machine and a bond to point to the role of money in a close relationship. A man and woman can be happy and make music together–the guitar–even indulge in interesting sex–the handcuffs but in the long run, they have vowed to stay together until “death us do part”–the skull and magpie stealing the wedding ring. In the face of death, the meaning of the guitar changes and the young man in his socks becomes Orpheus seeking Eurydice. In fact, the jutting precipice, thrusting into the mist, seems to exist in the same Hades as that of Persephone, where Eurydice is waiting for rescue.

Loren Holland. The Pact (2018)

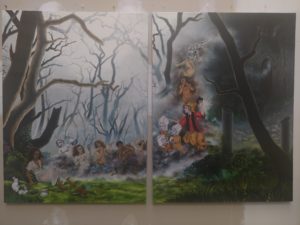

Holand knows how to conjure imaginary landscapes into believable grounds that rests upon contradictions. The trees are always bare and wintered, while the grass is always green and lush. Water and sky are always blue, belying the unpleasant stories of rape and death and oppression that must be unearthed through her iconographic codes. Despite the sense that the artist is calling upon the tradition of the religious paintings on multiple panels, these canvases are alive with nerves and disturbances. It is difficult, perhaps, in these disturbed times for a person of color, sensing a return to a pre-colonialism and an atavistic past, to feel anything but uneasy–dis-ease. This sense of foreboding rushes out to the open in The Devil’s Workshop, which is bursting with the Sluagh, a hoard, straight out of Celtic mythology, rushing into the foreground. This swirl of soul takers went by many names, all frightening, “Underfolk,” “The Wild Hunt,” or “The Host of Unforgiven Dead.” Pronounced sloo-ah, the shadowy forms of the dead were fairies gone wrong in Irish tales, but when Christianity came to Ireland, the Sluagh were rewritten as restless dead. Never mind if these misgotten beings are evil fairies or unrepentant sinners, they are coming for you and are highly dangerous. Haunting the night and dreams, the Sluagh, were described by an Irish website as dangerous because, “..humans are still very much their prey. The Sluagh exists on stealing the souls of the living, and especially the dying. Huddling and hiding in forgotten and dark places, they lay in wait for nightfall. Once the sun has left the sky, they strike out, in what, to the untrained or unsuspecting eye, appears to be a vast and ominous flock of large ravens or other birds. Flapping wings, screeching, and a whirlwind of undulating shadows are all you’d witness as the Sluagh descends for an attack. Owing to the folklore of the Wild Hunt, countless cultures and legends still link blackbirds (and especially ravens) as evil omens or signals of upcoming misfortune. In Irish mythology, the Sluagh were said to fly in from the west to steal a dying soul before it was given Last Rites. To this day, doors and windows on the west sides of houses are kept closed if there is a sick or dying person at home.” The Sluagh live in the West, the land of the setting sun and the coming of night. They will rise up at the news of a soul fading and rush through the air to attempt to snatch the dying before death. To thwart this attempt at the gravest sort of theft, the doors and windows facing West are always kept shut and bolted.

Loren Holland. The Devil’s Workshop (2018)

Creatures of the air, these wind-born fairies were terrifying creatures of the air, belonging, not to the earth or to water, but to the harsh gusts of winter. The “Sluagh Sidhe” or “Fairy Host” were Celtic versions of angels, and, like Lucifer and his followers, the fairies were banished from heaven, but live to torment the living on earth. The Hosts had the disconcerting habit of swooping down upon helpless humans they needed to do tasks for them as slaves. These fallen Christians become “..spirits fly about “n’ansgrioslaichmhor, a siosagusasuas air uachdaran domhain mar natruidean’ (“In great clouds, up and down the face of the world like the starlings, and come back to the scenes of their earthly transgressions.”) The Sluagh ride plant stalks and shoot darts of sickness to hasten death and their diabolical gathering of souls. The Hoard is depicted by Holland as an avalanche of dissolute sinners, pouring as if from a spout towards a modern woman. Like all of Holland’s women, she cowers on the left-hand side of the huge canvas in her transparent nightgown, having a nightmare, dropping like Alice down the rabbit hole of nightmares. The women among the Host seem to have died from tormenting themselves while trying to “improve” themselves according to cultural expectations: one injects fat into her buttocks, while another tried to lighten her skin with bleach, and eighteenth-century aristocrats in their white wigs rebuke the coiling hair of the recoiling victim. The meaning of the Sluagh becomes clear: they are soul stealers. They rob black women of their authentic selves, by plying her with white dreams of “white” (straight) hair she cannot fulfill. They haunt her dreams, they take advantage of her desire to belong, to fit in. They come from dark places to obscure the light and the sun.

Loren Holland, James Panozzo of Launch Gallery, and Holly Tempo

The twin themes of Holland and Tempo become clear. They are postcolonial artists who are picking up the bits and pieces of (male) colonial discourses in order to resist the metanarratives by re-purposing the dominant parole. By inserting the biography of the Other into the myths of the One, they destabilize the meanings by opening closed pathways and freeing silenced voices. Importantly, though, both Holland and Tempo retain the parlances they appropriate, whether the codes are formal and abstract or whether they are didactic myths. Philosopher Jacques Derrida explained these philosophical strategies: “By means of this double, and precisely stratified, dislodged and dislodging, writing, we must also mark the interval between inversion, which brings low what was high, and the irruptive emergence of a new ‘concept,’ a concept that can no longer be, and never could be, included in the previous regime.” In other words, the task these artists have undertaken is to break open–deconstruct–a constructed system in order to play with its suppressed possibilities. Tempo walks into the exclusive arena of painting, and, understanding that distilled to their essence marks are a malleable language, which is both synchronic and diachronic, she swerves away from a pointless confrontation. Like Holland, she tempers the borrowing of a male derived system by re-placing the mechanisms of power and turns them around to reveal how people of color are marginalized. Holland’s tactics involve her writing between the lines, slipping the experience of the black female into ancient tales, many of which have been used to control women. Métissage insists on keeping all the parts, weaving them in with new strands, mixing voices and genres and messages. It is important to retain the old cadences, for which these artists gently push to the background, so that the new soprano voices, singing songs of their lives and knitting them into new forms of mythic writing. Music in the African culture is woven of call and response.