Bringing Streamline Design Home

Norman Bel Geddes (1893-1958)

Today the name “Mar-a-Lago” is on everyone’s lips but for all the wrong reasons. The current owner is not important in the history of design but the architect for this famous dwelling was and should be today. Austrian born architect, Carl Maria Georg Joseph Urban (1873-1933), known as Joseph Urban in America, designed the famous home for Marjorie Merriweather Post, who could hire the best. The name of the home translates to “sea-to-lake” and the cereal heir wanted the best of everything, including the sought-after architect, who had designed a new annex of the Abdin Palace in Cairo for the Khedive of Egypt when he was only nineteen years old. From this auspicious beginning, the Austrian theatrical designer became well-known in Vienna, but Urban chose to leave his Secession colleagues and his career behind to come to Hollywood and New York. Finding America so hospitable, Urban never left, revolutionizing the Ziegfeld Follies in 1915–upgrading a somewhat tawdry girlie show by sheer artistry to a thoroughly respectable spectacle. In 1917, he also took over designing over fifty-five productions for the Metropolitan Opera. What Urban brought to Hollywood and New York City was a new approach to theatrical design called “new stagecraft” which replaced slavishly imitative recreations of real-world settings with what could be termed an American version of a Gesamtkunstwerk or a total work of art. The book, Designing Modern America: Broadway to Main Street by Christopher Innes, described his achievement in theater in these terms: “Controlling every aspect of the staging, Urban was able to impose complete imaginative and visual unity. This was his guiding principle, and he extended it beyond opera to culture. For Urban, achieving this kind of unity meant discarding all practices and conventions from the past. To be effective, everything—in designing a lifestyle, as on the stage—had to reflect the dominant ideas of the period.” Urban created an “impression” of the play’s mood or concept through colored lighting that could transform set decor. In order to control the layout of the stage, he created “inner frames” that could enclose an area of the proscenium and made sure that he and his team were in charge of making original sets and costumes so that all elements of the total experience were coordinated.

Mar-a-Lago under construction around 1926

Having met Marjorie Post through Ziegfeld, Urban designed her dream home in Florida. As Innes explained, “Urban made a conscious attempt to create a specifically American style of grand architecture based on local themes and materials: in this case an appropriately Floridian image, drawing on the history of Spanish colonists, the first Europeans to arrive in the area, combined with the Moorish background of their homeland.” Even with the current fame of Mar-A-Lago, today the name of Joseph Urban is not well known but he was very influential in design in 1920s America, moving with ease from architecture (he designed the New School in New York, winning out over Frank Lloyd Wright) to posters to automobiles to household goods. His complicated career is beyond the scope of this website but Urban, who sadly died in 1933, provided a role model for the new generation of designers, quite a few of whom started with American theatrical design–new stagecraft–and moved into the new field of industrial design during the 1930s. If Urban is forgotten, his successor is better known, and Norman Bel Geddes, began as a theatrical designer and walked away from his success in the theater in order to become something brand new: a designer who was willing to take the chance on an emerging field: designing household goods and appliances.

After a decade of success in theater and film, Bel Geddes arrived at a crossroads. His wife, the “Bel” of his name, left him and his concepts about movie sets were suddenly outdated by the arrival of sound or “talkies.” His path changed in 1926, as the author, Alexandra B. Szerlip, related, “..he was invited to spend the weekend at the Long Island home of Ray Graham, president of the Graham-Paige Motor Company, a small family-owned factory. To his delight, his fellow weekend guest turned out to be Gene Tunney.” The book, The Man Who Designed the Future: Norman Bel Geddes and the Invention of Twentieth-Century America, continued to explain the sudden change in direction: “At some point, Graham asked if Norman had ever thought of focusing his talents on the refinement of everyday objects. “Something sent the blood rushing through me,” he would recall decades later. “I didn’t glow; I burned all over.” The designer, boxer, and executive talked late into the night. By the time they parted company, Graham had offered $50,000 for a series of automobile designs, all expenses paid, the work to be carried out over the course of a year at Graham’s Detroit plant. If all went well, there’d be an option “at a figure considerably higher.” On the train ride back to Manhattan, Norman watched a dozen reapers mowing down a wheat field, almost in a single swoop; later, instead of the two or three silos of his youth, he saw a row of twenty. Industry was the future.”

Suddenly, Bel Geddes went from designing theatrical productions to designing cars. There were many car manufacturers following Henry Ford into what was an increasingly attractive business opportunity: enticing Americans into purchasing automobiles that were not the standard Model Ts and Model As. The Graham Brothers, Joseph, Ray, and Robert, originally from the farmlands of the Midwest, understood that Indiana farmers needed trucks which had yet to be invented. The brothers converted Fords to serviceable trucks by removing the existing car body and by 1920 they were reinstalling truck bodies–something they manufactured–onto the chassis. Another set of brothers were also in the fledgling truck business, the Dodge Brothers in Detroit who were initially connected to Henry Ford but both brothers died in 1920. The Graham Brothers decided to move to designing automobiles but in 1929 their dreams were derailed. Bel Geddes had designed five prototype cars for the company with the final version being very visionary. According to Szerlip: “..the “ultimate” Car #1, he anticipated the radiator placed behind a rounded grille (allowing the engine hood to integrate with the car body) and a windshield that slid vertically into the body. Driving lights, set low and between the mudguards, would turn with the front wheels; the fuel tank and trunk compartment would be built in, rather than added on; and the back license plate and back driving lights would be incorporated into the fender to help reduce air resistance. Graham’s engineers estimated that it would be able to travel fifty-eight miles per hour with the same power that existing cars required to go forty-five miles per hour. And for a touch of dash, white “trim” was added to the tires. According to at least one contemporary source, “whitewall” tires were a Bel Geddes innovation.” Sadly, this car, introduced in October of 1929, was never manufactured. As Bel Geddes wrote of his design for the Graham-Paige Company, “The car was never built, owing to psychological factors in the human make-up that have to do with timidity.” The Depression crashed upon the hopes and dreams of millions of Americans, but Norman Bel Geddes had seen the future and was determined to remain in the game.

The economic impact of the Depression upon the wider American society is well known but there were unexpected consequences of the horrific downturn. Businesses, however, reacted offensively, asking the question: how can we sell our products? The answer seemed to be to design entire new lines with a new look that would entice buyers (who could still afford the purchase price). As important as new designs were new products that would make a home more efficient, especially for the housewife who was fortunate enough to have a husband who would support a household. Despite the 25% unemployment, there was still a sufficient contingent of well-educated people in key or necessary positions, such as government, who would want to update their homes and their lifestyles. As the New York Times explained the new resolve: “During the Great Depression, American production was primed to run on all cylinders, but sales had slowed to a standstill. Good design was hailed as a solution to consumer inertia: ‘The appeal of efficiency alone is nearly ended,’ the adman Earnest Elmo Calkins wrote in a 1927 essay, ‘Beauty the New Business Tool.’ ‘Beauty is the natural and logical next step.’ He advocated a practice called ‘styling the goods’ or style ‘engineering,’ making familiar products look ‘new, and desirable’. A generation of designers working in architecture, advertising, packaging, interior design, graphic, and scenic design came to believe that commonplace goods and appliances, from automobiles to pencil sharpeners, could benefit from contemporary veneers — and some serious retooling. This philosophy underscored the advent of a new field of industrial designers, the white knights of American industry.” In the early 1930s, a new-minted Bel Geddes presented the look of the future, Streamline Moderne, to the design of American objects.

Erich Mendelsohn, Red Banner Textile Factory in Leningrad (1926)

Writing for The New York Review of Books, Martin Filler credited German designer Erich Mendelsohn, who Bel Geddes had met in 1924, with pioneering work in “streamlining.” “Mendelsohn’s dynamic, crowd-pleasing commercial buildings featured curved corners, wrap-around horizontal bands, and elongated proportions—motifs that the Geddes firm adapted for everything from practical household objects like refrigerators, lamps, and vacuum cleaners, to hypothetical plans for mechanized theaters, amphibious cars, and floating airports.” But as Filler noted, Bel Geddes sought to establish the idea of streamlining objects as more than a new design to capture the imagination of consumers. In his book, Horizons (1932) he insisted that “It is a well-known fact that a drop of water falling in still air assumes an almost perfect streamline form. The form is approximately that of an egg, though the small end of the drop tapers more sharply to a conical point. In falling, the larger and blunt end of the drop is foremost. This is the shape that creates the least turbulence in the form of eddies and partial vacus which increase wind resistance.” If, as Bel Geddes insisted, the shape–the drop–its curved outlines were natural and inevitable, then an object moving through space as globules of rain falling through space would naturally have a “streamline” shape. Motor Car No. 9 of 1933 was a strange tadpole of a car with an organic shape and organic teardrop add-ons was an experimental car that was too out of the realm of American imagination to ever be manufactured, but Bel Geddes made his point. The Harry Ransom Center described the visionary automobile: “It offered excellent visibility through the use of curved glass for the windshield and windows. The steering wheel and single headlight were in the center. The car featured a vertical stabilizer, or rudder, in its tail, like an airplane. The front and rear bumpers were made of chrome, and the rear bumper was attached by three hydraulic shock absorbers. This design offered good use of interior space, providing seating for eight.”

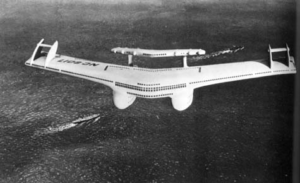

The logic of Bel Geddes is simply enough. If a car moved through space and it did; if an automobile cut through a stream of air which had to flow seamlessly over the surface, then–inevitably–the shape had to be aerodynamic. But there is more than science in the philosophy of the new industrial designer. As if to forget or negate the Depression, the 1930s was also a decade that used science fiction to gaze towards the future. Born in 1928, Buck Rogers appeared in Armageddon 2149 by Phillip Francis Nowlan, as “Anthony Rogers” a present-day Air Force colonel in a coma who woke up in the twenty-fifth century. The future and its toys were part of the imaginative world of Americans in the 1930s and futuristic looking cars were coming of age in the real world. Bel Geddes reestablished himself as a designer who was also a visionary and he often opined about the future. In 1932, he wrote Horizons, a book that called for modern design to be responsive to the increasing speed of planes, boats, and automobiles and anything else that moved. Bel Geddes was particularly concerned about wind resistance and the proper surfaces the allow the air to move past smoothly. In writing of an ocean liner he designed–the book is full of speculative projects–he said, “The entire superstructure is streamlined. Every pocket of any kind whatsoever has been diminished. All projections have either been eliminated or enclosed within the streamlined shell. The single protrusion is the navigator’s bridge and this is cantilevered and similar in shape to a monoplane wing, consequently offering a minimum of resistance to the air.”

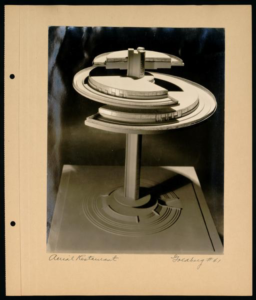

Model of Aerial Restaurant 1930

Model of Aerial Restaurant 1930

The “indispensable visionary” as he was termed wrote “Ten Years From Now” for the Ladies Home Journal in 1931, predicting for example that “Synthetic materials will supplement wool and cotton in clothing” and that “Crops will be artificially stimulated” and that “Talking pictures will replace talking professors,” among other ideas that came true. In addition to having a futuristic mentality, Bel Geddes also understood, both from his career in theater and then as a product designer, the persuasive power of psychology–how to move a spectator. In his article, “Transforming the Audience: Theatricality in the Designs of Norman Bel Geddes,” Dr. Nicolas P Maffei wrote, “Artists who knew of Freud’stheories of the unconscious understood the expression of repressed feelings as an essential aspect of the modernist project. Geddes’s designs depended upon his knowledge of emotional, psychological and spiritual transformation, and expressed a belief that design could provide a therapeutic experience. It could alleviate what he and many of his contemporaries viewed as a spiritual malaise within an increasingly mechanized world. The idea that consumption could be stimulated through the release of repressed desires would have had great appeal, especially after the 1929 stock market crash” Maffei noted that Bel Geddes used his knowledge of the mechanics of psychological desire and theater design for his early window displays for the Franklin Simon department store between 1927 and 1929. Bel Geddes wrote that “..the store window is a stage on which the merchandise is presented as the actors..The window must ‘arrest the glance; focus attention upon the merchandise; persuade the onlooker to desire it..” Good design could also, in the mind of Bel Geddes, according to Maffei, could manage a company’s image, or mold a client’s mood and that a well-designed office would put the visitor into a receptive frame of mind.

Bel Geddes, the man of much imagination, also redesigned the traditional American home. In Horizons, written just on the edge of the extinction of the Bauhaus, he eliminated the “styles” from the past, Tutor, Cape Cod, Victorian, and so on, in favor of a flat roof dwelling. “..the modern house may differ, considerably, if not radically, from the wall-bearing structure to which we have been accustomed. If it has a steel frame, the interior and exterior walls, partitions, floors, and roof are all carried by this skeleton structure.” He advocated “curtain wall construction” to increase window areas so that bands of windows can deliver different kinds of light to “the furthest corner of the room..With modern construction methods, the pitched room becomes unnecessary.” Within the home itself, Bel Geddes would install built-in furnishings tucked into the walls in order to open up a large central space. Cabinets and bureaus could be part of the structure, leaving ample room for other items such as sofas and chairs. Kitchens, likewise would be standardized and composed of built-in elements. For the newly flat roofs, he imagined that roof gardens would bloom and, like the Bauhaus architects, the designer foresaw the day of prefabricated construction. One of the great leaps of imagination—technologically impossible in its own time and difficult even today–was the so-called Aerial Restaurant designed for the Chicago World’s Fair for 1933. The three-level restaurant was cantilevered on a thirty-two-foot shaft so that the “main mass does not spread out until it has reached a considerable height above the ground. Hence it does not interfere with the two and three story height of nearly all other buildings proposed by the fair.” Bel Geddes proposed that the glass-walled restaurants slowly rotate. Of course, a restaurant such as his Aerial vision could not be built but it predicted the Space Needle for the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle, an oval observation deck with a restaurant on a tall shaft. Although Norman Bel Geddes spent much of the 1930s imagining a future that would never arrive, he also designed numerous objects to populate the real world of the ordinary home. These objects will be discussed in the next post.