The Delaunays and Modern Life

Paris Between the Wars,

In 1889, the year that France celebrated the centenary of the Revolution, is best known for the shock of the new tower rising from the Champs de Mars, the Eiffel Tower, but that year was also the year that the first steps were taken to electrify Paris. Today Paris is known as “the city of light,” but as the nation of France approached the twentieth century, it was suddenly realized that the capital city was falling behind other European nations in adopting the latest in lighting technology–electricity. Writing in 1911, A. N. Holcombe noted that not until the Opéra Comique burned down did the officials awaken to continuing danger of using gas for public buildings. The article of 1911, “The Electric Lighting System of Paris,” is as boring and straightforward as the title, detailing the long process of installing a new means of illuminating the city, from putting “underground conduits and wiring” in place to deciding what fixed price should be charged and determining how the private companies undertaking the enterprise should be compensated in relation to the capital investments made by the state. By 1907, the year of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, the public had accepted the switch (so to speak) from gas to electric and the demand for installation far exceeded the speed of the companies, which, being private, needed more investment funds. The tangled tale involved how the government should deal with private for-profit companies serving the public and how both entities should deal with labor.

Sonia Delaunay. Electric Prisms (1914)

A. N. Holcombe’s article in the Political Science Quarterly noted that when all the companies were merged into one company, the Paris Electricity Supply Company, capitalized by the city was given an exclusive contract that would begin in 1914 and extend to 1940. The city-owned the plant(s) and the company was given access to “the exclusive use of the property.” What is interesting about this article, now over one hundred years old, is that, in its own dry fashion, illustrates how new and novel public electric lighting would have been in the Paris of Robert Delaunay and Sonia Terk-Delaunay, artists who were dazzled and enchanted by this burst of modernity. In the evenings before the Great War, the newly married couple would stroll down the Boulevard St Michel where the new lights were providing a sharp brilliance, blindingly radiant in comparison to the mellow glow of gas. She remembered, “Halos were making colors and shadows turn and vibrate around us, as if unidentified objects were falling from the sky, friendly and crazy.”

Sonia Delaunay. Electric Prisms (1913)

In her interesting article on the impact of electric lights on artists, Christine Poggi wrote that when the street lights were installed on the Boulevard St. Michel were installed just before 1913 both Delaunays made sketches of the people of Paris, drawn to the novel sight, congregating under the bright lights. “The new arc lights can be viewed as one of the modernizing effects of Haussmannization, in which expansive new boulevards, among them the Boulevard St. Michel, cut through the narrow streets of old Paris, opening them to greater circulation and the production of new forms of visuality and spectacle. As Wolfgang Schivelbusch observes, arc lights were like small sums with a spectrum similar to that of daylight. In contrast to the gas lamps they replaced, they were extraordinarily bright and could not be looked at directly. As a result, they had to be fixed much higher on posts, where they were out of view. For those entering one of the places illuminated by arc lights from a dim, gas-lit side street, the transition could be dramatic. Delaunay’s memoir evoke her experience of the modernity of the site, the brilliant color and disorienting spatial effects created by the arc lights inducing a sense of ‘madness.'”

I liked electricity. Public lighting was a novelty. At night, during our walks, we entered the era of light, arm-in-arm. Rendez-vous at the St. Michel fountain. The municipality had substitued electric lamps for the old gas lights. The “Boul Mich,” highway to a new world fascinated me. We would go and admire the neighborhood show. The halos amde the colors and shadows swirl and vibrate around us as if unidentified objects were falling from the sky, beckoning our madness.

But, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the blossoming of electric street lights, marching from neighborhood to boulevard, was not the only modern innovation that captured their attention. Elsewhere, far away, an extraordinary railway–the Trans-Siberian Railway–was being completed in Eastern Russia. Alarmed by the moves by China to build a railroad up to the Eastern borders of Russia, Tsar Alexander III began the project–intended to protect the Russian Empire from any Chinese incursion–in 1890. The father wrote to his son, “I desire you to lay the first stone at Vladivostok for the construction of the Ussuri line, forming part of the Siberian Railway, which is to be carried at the cost of the state and under direction of the government. Your participation in the achievement of this work will be a testimony to My ardent desire to facilitate the communications between Siberia and the other countries of the empire, and to manifest My extreme anxiety to secure the peaceful prosperity of this country.” His heir Nicholas I finished the “Great Siberian Way”, as it was called, twelve years later, and the completion of this major route of trade and transportation was arguably the finest of his few achievements. The Railway stretched from Moscow to Vladivostok but it was built on the cheap and during the 1903 war with Japan, the rails failed and the system sagged and collapsed with the Empire itself. In a little-known footnote to history, just before the Russian Revolution installed a Soviet system of a worker controlled Communist state, it was the most capitalistic nation in the world, the United States of America that sent in workers and engineers in 1917 to help the fledgling Provisional Government to repair the Railway and re-built all 5,772 miles correctly. Even today, the prospect of riding nearly six thousand miles on a famous railroad is tempting and in the early twentieth century, the journey was a luxurious one–if one had the money. Certainly, the feat of modern engineering fired the imagination of the Russian poet Blaise Cendrars, who wrote Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway and of Little Jehanne of France, a long folded expanse of text designed and decorated by his friend Sonia Terk-Delaunay. Produced through a combination of Linotype printing and the use of colored stencils (pochoir), this is a truly remarkable poem because its sheer size and length mimics the long railway itself. Because we usually see this “poem” as a small colorful illustration in a book, the explanation of the Tate Museum about the impressive size of this work of art is helpful:

(The poem was) produced in Paris in 1913 and published by Cendrars’s own self-financed publishing house, Éditions des Hommes Nouveaux (New Man Publishing). The text and artwork was printed on a single sheet of paper, folded accordion-style to form the twenty-two panels. When unfolded it is two metres tall. The original print run was intended to be 150 copies, which, if laid end to end, would be the same height as the Eiffel Tower, however only sixty editions were printed. Due to its large scale, Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway only functions as a readable book when it is fully open. Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway stages the unification of text and image and is a key example of the ‘simultaneisme’ (simultaneous theory) developed by Delaunay with her husband, fellow artist Robert Delaunay…Delaunay’s artwork was not an illustration of Cendrars’s narrative, but a visual equivalent, intended to be seen in unison. She transcribed the poem in colours, as she heard it being read out..

In this wonderful stream of consciousness poem, the narrator travels which his companion, Jehanne, described “a young proletarian,” who keeps asking: “Blaise, tell me, are we far from Montmartre?” And the poet answers: “For pity’s sake, come here and I’ll tell you a story Come into my bed/Come to my heart/I’m going to tell you a story..” In the Delaunay couple, we have two artists who celebrate the modern innovations of the new century with their art. In fact, in this poem, Cendrars, who lived in Paris, wrote of the impact of electric lights. “Is raining electric globes/Montrouge Gare de l’Est Métro Nord-Sud ferries on the Seine world/Everything is halo/Depth.” The text was done in four different typographies with upper and lower case, in four colors–green, blue, red and orange. The design keeps the story unfolding, leading from “page” to “page” as sixteen-year-old Blaise tells the story of his experiences in 1905 on the Railway.

Sonia Delaunay and Blaise Cendrers.

Prose on the Trans-Siberian Railway and of Little Jehanne of France (1913)

In her article, “Mass, Pack, and Mob,” Poggi made the interesting observation that, after the War, “this quasi-abstract approach to depicting the city, and of the masses that inhabit it, would come to seem outdated, even decadent.” Post-war artists, she observed were interested in the “politically organized crowd” in contrast to “modern spectacle and entertainment.” But the Delaunays were not in Paris after the War. They had fled to Spain and from there to Portugal where they lived the war years. The Revolution put an end to Sonia’s Russian income, and she, the practical one in the family, opened a chain of shops, from Bilbao, Madrid and Barcelona, which sold her fabrics and her fashions, all designed by her, using patterns and colors inspired by her paintings. The couple stayed in the Iberian Peninsula for seven years before they returned to Paris. By the mid-twenties, Paris was in the midst of Les Années folles and the pre-war rivalry Robert had felt for Pablo Picasso was long ago and far away, in another time. According to Histoires de Paris,

Dès son arrivée dans la capitale, l’écrivain américain Henry Miller écrira : « La première chose qu’on remarque, à Paris, c’est que le sexe est dans l’air. Où qu’on aille, quoi qu’on fasse, on trouve d’ordinaire une femme à côté de soi. Les femmes sont partout, comme les fleurs.

For Sonia, these flower-like women were her target audience and she began her business anew in a city mad for new fashions. Unlike Robert, who had to reestablish himself, she had a place in the post-war world through her designs. As her biographer, Axel Madsen, wrote,

Sonia’s flair for adventuresome decorating, theater costume and book design, led her to adapt her bold color compositions, geometric designs, and swirling patterns to abstract dress designs. The result was a style that was different, a fashion that was decidedly avant-garde. This kind of haute couture could only be worn–and appreciated–by women who wanted to be noticed. Her clientele, therefore, included women who were known for their character and eccentricity, actresses and rich foreigners. To wear SoniaDelaunay was not, like wearing Chanel, to adopt a “look.” It was to make a statement.

Sonia was the main source of income for the couple who held court in their Paris apartment which was both decorated by painted poems by their friends and visited by the new Surrealist community. But their evenings and their dinner parties were not exclusively French. The Delaunays, in contrast to the rest of Paris, were happy to entertain Germans, including the Bauhaus architects. For Robert, the Bauhaus idea of joining art and industry was simpatico and for Sonia, the poems on the walls made their way into her architectonic dresses. In his book, Sonia Delaunay: Artist of the Lost Generation, Madsen reported on how the couple went from being hounded by bill collectors to being well-to-do, once they were established. They owned a dashing car, a Talbot, and were among the first artists in the 1920s to possess a telephone and own a radio. But this was on her earnings.

Sonia Terk-Delaunay’s designs for cars and clothes

In 1925, Art Deco was introduced to the French and to the world in an exhibition, the International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts, from which the new Style Moderne took its name. Art Deco, the preferred name, was introduced later, but in 1925, it became clear that the Cubism that had dominated before the War had become an applied art, incorporated into design after the War. Given the male-dominated character of the group, the fact that Sonia Terk-Delaunay took the heady concepts of Orphism and Simultaneity and made these terms buzz words for fashion. There was a simultaneous car, a simultaneous dress, coat, shoes and so on, popularizing Cubism at its most scientific and most esoteric, making the style into a luxury consumer good.

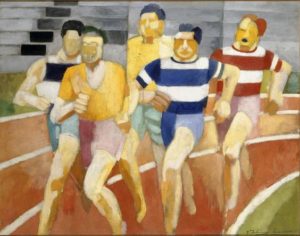

It was the 1925 exhibition that made her reputation while Robert was still trying to find his artistic feet. Apparently, Robert’s first post-war exhibition in 1922 at the Galerie Paul Guillaume was not successful, but he began a new series on the Eiffel Tower. Two years later, Delaunay returned to another pre-war theme, athletics, in his Runner paintings, which were far more conservative than the earlier paintings he did before the War. It seems that Robert, who was never inclined towards hard work, preferred to drive his fancy Talbot and entertain his friends to contributing to the family income. When the Delaunays needed money, he would make or sell art, and the paintings of the twenties and thirties were reiterations on his previous themes.

Robert Delaunay. Runners (1924-26)

However, in 1937, Robert Delaunay, in collaboration with his now famous wife, Sonia, got a chance to shine, one more time. He was invited to do the murals for the Palais des Chemins de Fer and Palais de l’Air at the Paris World’s Fair. Here the preoccupations of decades for the couple–the fast trains, the Trans-Siberian Railway and the glamor of air travel, going back to Louis Blériot–came to fruition. The World’s Fair was a futile gesture of hope in a Europe sinking back into another world war. The next and last post on the partnership between the leading art couple between the wars will concentrate on their murals in the Pavillon de l’aviation in Paris.

Robert Delaunay. Disques reliefs (1936)

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.