Squaring the Circle

Modernizing the Teapot

A third generation modern designer, Christopher Dresser (1834–1904) was the successor to the great British reform designer, Owen Jones, who had been the successor to William Morris. Dresser was a prolific designer and much of his work was highly decorative and very ornamental. But, he was also a precursor of modern design for his use of simple forms and shapes and straight and strong lines. In contrast to Mackintosh for whom straight edges were an aesthetic, the work of this Scottish designer—Dresser—can be considered a reference to the machine. In fact, he has been called the “first independent industrial designer.” However, his practice was an aesthetic split between Victorian exuberance and his lean and mean designs so modern we would assume they were invented yesterday. In fact, Dresser himself was a thoroughly modern success story. He came from a humble background and was trained, from the age of thirteen, as an artisan at the Government School of Design. As his educational background attested, his tenure at the School was that of a commercial designer, not a fine artist. But Dresser rose above the rank for which he was intended and, due to his study of flowers for ornamentation, became a well-known botanist. According to a review of Christopher Dresser 1834-1904: A Design Revolution at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2004, “His approach to decorative ornament was to stylise natural forms, finding the underlying geometry of a plant or flower and then turning it into abstract or semi-abstract pattern.” His drawings for his lectures broke the geometry of the flower down into component parts, leading to the “scale, simplicity and clarity of these early drawings,” which lead to his abstract design.

Married as a teenager at age nineteen, Dresser soon had a large family to support and worked for wallpaper companies such as Jeffrey & Co., designed ceramics for Minton and Wedgwood, and even created cast iron chairs and coat racks for Coalbrookdale. The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote of his astonishing rise as a designer, “In 1859, he received a doctorate in absentia in the field from the University of Jena, Germany. He was elected a Fellow of the Edinburgh Botanical Society in 1860 and a Fellow of the Linnean Society a year later.” Despite the freelance work in the service of the needs of others, Dresser became well regarded enough to be appointed by the South Kensington Museum (today’s Victoria and Albert Museum) to be its representative to Japan. He was traveling at an interesting time. Since its founding in 1852, the Museum had been collecting Japanese cultural artifacts, but the hub for artists was the East India House, a small part of Arthur Lasenby Liberty’s establishment in Regent Street. According to Nancy B.Wilkinson, “E. W. Godwin and Japonisme in England,” the artists referred to this collection as the “Japanese Warehouse.” In an article of 1876, artist and furniture designer, Edward William Godwin, who often worked with James Whistler, “No. 218 Regent Street is from front to back and top to bottom a warehouse literally crammed with objects of Oriental manufacture.”

In 1876, at the peak of the English interest in the art of Japan, Christopher Dresser was sent to Japan. People of money and taste collected Japanese art objects and designers and artists were impacted by the aesthetic principles of Asian designers. But it was Dresser who actually went to Japan–the first European designer to arrive on its shores–and researched the histories and traditions of the objects themselves. His 1882 book, Japan, Its Architecture, Art, and Art Manufacturers, was almost encyclopedic in its attempts to educate the English on Japanese culture. He explained to his readers about Japanese ceramic ware, often spelled with a “k,” and how it was used in tea ceremonies. “At the beginning of the sixteenth century a Corean (we now use a “K’) potter named Ameya came to Kioto (today we would use a “Y”), where he made a common black earthenware with lead glaze. This is especially valued for use at the “tea ceremony” (cha-no-yu); and for eleven generations the descendants of this man have made the same wares. So esteemed was the ceremony by Shôgun Taikosama that he honored this particular manufacture with a golden seal, on which the character “rake” (meaning enjoyment) was engraved.” Later on Dresser wrote that he was invited to a tea ceremony which had once been private and secret, evolving from an event between the “master” and the guests, no servants allowed, to a more ‘fashionable character.” Dresser stated,

The great peculiarity this tea-drinking ceremony consists in the exactness with which everything is done. A spoon, cup, ladle, or whatever is handled, has to be taken hold of in a particular way, set down in a particular place, and touched in a particular part; and everything is done with the same stance precision. What i saw was part of the ceremony of “thin tea-drinking,” and part of the ceremony of “thick tea-drinking;” but the whole is simply a lesson in those laws of politeness, which were formerly so rigidly extracted in every mansion and on every state occasion, and which are largely kept up in the houses of the old aristocracy.

In 1873, Dresser wrote Principles of Modern Design in which he said that his aim was “to bring about refinement of mind in all who may accompany me through my studies.” Characterizing himself as an “arts manufacturer,” he believed that “the man who can form a bowl or a vase well is an artist, and so is the man who can make a beautiful chair or table. These are truths’ but the converse of these fats is also true; for it a man be not an artist he cannot form an elegant bowl only an artist could make a beautiful chair or an elegant bowl, nor make a beautiful chair.” If he or she used the term “artist” or not was unimportant. For Dresser, the other side of the equation was an educated consumer. What did it matter if a beautiful object was well designed if the viewer could not appreciate it? The expanded meaning of “design reform” would be “education reform.” Dresser’s many books were companion pieces, if you will, to his sophisticated designs, educating the public. He stated his goal in his book: “My primary aim will be to bring about refinement of mind in all who may accompany me through my studies, so that they may be individually be enabled to judge correctly of the nature of any decorated object, and enjoy its beauties—should it present any—and detect its faults, if such be present. This refinement I shall attempt to bring about by presenting to the mind considerations which it must digest and assimilate, so that its new formations, if I may thus speak, may be of knowledge.”

Christopher Dresser. Studies in Design (Cassell, Petter and Galpin, 1876)

Dresser was making the point that design was now the province of artists whose job it was to elevate the taste of the masses through good design, which, for him, included both ornament and decoration. No matter how rectilinear and simplified his designs became, Christopher Dresser never questioned the importance of additive motifs. In an 1874 lecture, “Eastern Art, and its Influence on European Manufacturers and Taste,” Dresser specifically put ornament and rationalism together: “The ornamentist should stand between the pure artist on the one side and the utilitarian on the other, and should join them together. He should be an artist in every sense of the word, yet he should be a utilitarian also. He should be able to perceive the utmost delicacies and refinements of artistic forms, yet he should value that which is useful for the very sake of its usefulness.” This is a very interesting discussion for Dresser was very interested in understanding how beauty and “utility” worked together. The idea of “beauty” would not be addressed by early twentieth century designers, but Dresser was very concerned with how good design resulted in what he called “beauty.” The example he used was a tea kettle and a Turkish samovar, a large container for hot water, often used in England for tea. The kettle in question was an example from Japan, a major source of inspiration for Dresser who commented, “It is curious that while the kettle is an object in use in every house in the land, we have to go to Japan to learn how to make one as it should be made. But we are a pig-headed, self-opinionated people, who blindly persist in our ignorance. We do not give though to what we do, but insist upon doing those things which our fathers did, just as our fathers did them.” Dresser had visited the London Exposition of 1862 where he saw Japanese art and artifacts. Like many artists and designers of his generation, he became enamored of Japanese design. Japanese design was in fact quite elaborate but what Dresser learned from the exhibition was the importance of shape and the necessity for the material selected to be suitable to the form.

Christopher Dresser. Japanese Inspired Minton Teapot (1880s)

“Japanese Crane”

This is Dresser the reformer, but he is also Dresser the designer who will take the good design of the Japanese kettle and note that it has several qualities, shape, which is perfect for heating, a strong bottom, which was functional double metal. The kettle can be comfortably picked up with ease by a “smooth and beautiful” handle, which, although Dresser did not mention this stayed cool to the touch. He then compared the simplicity and beauty of the Japanese example in comparison to the English manufactured equivalent. He said,

“From Wolverhampton our kettles chiefly come yet to what Wolverhampton manufacturer could I say, “You do not know how to make a kettle”, without subjecting myself to severe reproof. Yet it is a fact that none of them know how to make this common object as it should be made. Where is the English kettle, I ask, which as utilitarian qualities comparable with those of the Japanese example; and where can we find kettle with art qualities equal with those under consideration? We could excuse the want of artistic beauty to an extent as we are only now becoming alive to our ignorance in matters of taste; but with humility I say that we, with our boasted utilitarianism cannot construct a common kettle rightly as a merely useful object.”

Of course, Dresser would design his own tea sets. He worked with various manufacturers, usually using silver and often ebony for the handles. One of the characteristics of his work in the 1880s was the smooth surfaces, wiped clean of the crusts of hammered out design. The tripart set he did for James Dixon & Sons, Sheffield in November of 1880 was assembled out of the most simple components, three circles for the tea pot, the covered milk container and the sugar dish with domed lid. To offset the spheres, the ebony handles on the pot and milk jug were simple straight lines, and the set of legs on each vessel were slim and splayed delicately. There is also a matching coffee pot which, as was historically customary, dating back to George Berkeley, was tall and oval with the same distinctive straight handle and tiny legs poised like a ballet dancer en pointe. Dresser did some sixty designs for Dixon, but not all of them were manufactured and stayed, perhaps because they were too radically plain, on the drawing boards.

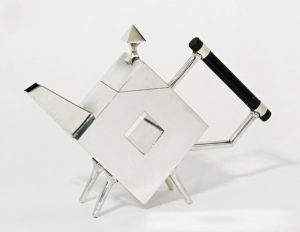

Perhaps Dresser’s most famous like of pots were the squared tea pots he did for Dixon in 1879. Described as “English Japanese” in the “costing book,” this series of pots were Electroplated nickel silver and the handles were ebony. What makes this series unique was not just the unexpected use of a square, set on its diagonal point, instead of a circle but also the fact that the square was opened up with another square cut through. The top of the diamond/square was sliced off and repurposed as a top, capped with an arrow shaped design. The spout is equally rectilinear, as was the now familiar handle and straight thin legs. The Library Director, Stephan Van Dyke, of the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum explained that these pots were designed with an industrial destination in mind. “A key thing to remember with Dresser is that he liked materials; he’s experimenting with new materials. He also knew the manufacturing process so well, which is a real plus. If you knew how things were manufactured, you could manufacture them better.” Van Dyke noted that, like most designers of his time, that Dresser did not “originate.” Instead, he was a synthesizer of many influences, especially from Asia. One can only assume that the designer had a particular customer in mind–someone sympathetic with the Aesthetic movement. Dresser’s designs were very sophisticated and would have not appealed to the average middle class family. These pots are small and seem to be designed for tea for one or maybe for two. It is possible that the audience for this kind of modernity would have been one of fellow artistic producers. Van Dyke continues, “The goal was to make good design available and even affordable to many people. Dresser understood his clientele. Some of his materials were very avant-garde for the time, but many of them fitted into this new emerging middle class that was looking for new things. They were looking for affordable, modern and curious things to furnish their home.”

Christopher Dresser. Teapot for Dixon and Sons (1879)

It would be incorrect to understand this extraordinary set of square pots in terms of industry and manufacturing only. Dresser was a product of the Aesthetic movement and was an inheritor of the reformist desire to reform middle class taste and to transform the prevailing definition of “beauty.” In contrast to Victorian elaboration of everything and ornamentation upon anything, Dresser’s designs combined form and function with a new sense of beauty lying in the purity of a simple geometric shape, a circle or a square. On the rare occasions when he did engrave his tea sets the designs were spare and geometric, nothing natural, only straight lines and a clean pattern repeating the shapes themselves. Dresser may have been hoping the newly adventurous middle class with some amount of disposable income would be interested in buying something untraditional but he was careful to put art first and manufacturing potential second. Today these severe and unexpected tea services are still contemporary. The design of Christopher Dresser manifested themselves in ways the artist could no have imagined: the tea pots glided from century, fitting neatly into Art Deco, Mid-Century and the twenty-first century, ageless and timeless. That quality of always being contemporary and dateless is very rare, but good design should be always satisfying and complete as an artistic expression.