Welcome to the Vortex

One hundred years before Europe began to industrialize and enter into the modern age, England was already totally involved in what would be called the Industrial Revolution. This Revolution, one of those rare historical events that change everything, actually began in Great Britain and visitors from Europe who wanted to see the future had only to walk the streets of London. writing for Georgian Britain Michael White recounted the rapid transformation of a rural society in a mere few decades of the eighteenth century.

Constant power was now available to drive the dazzling array of industrial machinery in textiles and other industries, which were installed up and down the country. New ‘manufactories’ (an early word for ‘factory’) were the result of all these new technologies. Large industrial buildings usually employed one central source of power to drive a whole network of machines. Richard Arkwright’s cotton factories in Nottingham and Cromford, for example, employed nearly 600 people by the 1770s, including many small children, whose nimble hands made light-work of spinning. Other industries flourished under the factory system. In Birmingham, James Watt and Matthew Boulton established their huge foundry and metal works in Soho, where nearly 1,000 people were employed in the 1770s making buckles, boxes and buttons, as well as the parts for new steam engines.

A hundred and fifty years later, at the beginning of the twentieth century, Great Britain was at the top of the world, dominating all other European nations and yet, perhaps because of a preoccupation with empire building and industrial might, lagging behind in the arts. The facts and figures tell the tale: by 1900 85% of the population lived in towns, London alone had four and a half million inhabitants, and in 1914, England a tiny island, had amassed a great empire, covering one fifth of the earth. The social and psychological instinct in the face of such rapid metamorphosis was to retreat into the past and the British public, after some initial hesitation, embraced the brilliant narrative paintings of the Pre-Raphaelistes and spent the nineteenth century revisiting long lost times. But by the second decade of the twentieth century, the bill for industrialization and empire had come due–the culture had to reckon with its own modernity. The world, Ezra Pound, asserted had fallen into a vortex and, he wrote in 1914, “The vortex is the point of maximum energy. It represents, in mechanics, the greatest efficiency.” The best way to explain the vortex that was the past and the future breaking apart was an art that confronted the machine itself–Vorticism.

After a century of decorous exchanges with the Royal Academy, the British art scene could look back to the rebellions of James Whistler (1834-1903), an American expatriate artist, who went his own way as an avatar of the fin-de-siècle avant-garde. However, ten years after Whistler’s death, for London, Post Impressionism was considered the avant-garde. These daring artists, led by Walter Sickert (1860-1944), congregated decorously in “groups,”the Camden Town Group and the London Group. These British Post-Impressionists stopped short of the shores of Cubism but dappled with a careful cross-breeding of English artists and continental artists of the same era. For example, Sickert combined Whistler and Edgar Degas (1834-1917), who were friends in real life, and sprinkled in some early twentieth century touches from Paris with his psychologically penetrating portraits of Edwardian life. Sickert had lived in Dieppe until 1906 and surely knew of current Parisian movement, yet when he returned to London to preside over a small group of progressive artists, such as young Spencer Gore (1878-1914) in his studio on Fitzroy Street, he remained affiliated with a Whistlerian version of Post-Impressionism. The “Fitzroy Street Group” evolved into an independent exhibiting society which evolved into the “Camden Town Group” which became the “London Group.” It was just this sort of belated and backward response to modernity that infuriated yet another element of London’s small avant-garde world, a handful of young men and women who would decisively break away from the languor of Edwardian England–the Vorticists.

In the summer of 2011, the Tate Museum acknowledged the only British avant-garde movement of the early twentieth century in the exhibition, The Vorticists: Manifesto for a Modern World. Earlier that year, the Guggenheim Venice presented the first show on Vorticism in Italy, The Vorticists: Rebel Artists in London and New York, 1914-1918, its title underscoring the fact that many of the prominent figures in the movement were of English-American-Canadian origin. The exhibition traveled to the Tate Britain, completing its odyssey through time, returning home. This comeback, after a century of being ignored, underscores the fact that “Vorticism,” as a movement, scarcely figures in the annals of modern art. For nearly a century this strange and seminal movement, so indicative of its own time, was overlooked by art history. The swan song of Vorticism happened in New York at the Penguin Club where the art was exhibited in the winter of 1917, just as America was busy entering the Great War–not the best time for an art show. Then in 1956 the Tate attempted to set the record straight by presenting Wyndam Lewis and Vorticism, but the public was uninterested. Perhaps the bombastic attitude of Lewis who said, “Vorticism was what I personally said or did at a certain period,” dampened enthusiasm, especially since the movement’s founder, Ezra Pound (1885-1972) had been associated with proto-Fascism. During the fifties, the art critics were hostile to Lewis and artists were looking towards the continent, particularly to Paris for guidance. Vorticism languished in the shadows.

Not until 1976 did the great British historian, Richard Cork, did a substantive account of the ill-fated avant-garde movement emerge. Today, Cork’s Vorticism and Abstract Art in the First Machine Age: Origins and Development, Volume I and Volume II can be purchased for hundreds of dollars. This large project was preceded by the author’s 1974 book, Vorticism and its Allies, the catalogue of an exhibition of an exhibition at the Hayward. The fact that there have been exhibitions is significant because, according to Cork, much of the art made during those few years is missing. Reprising his role as the chief chronicler of this obscure moment in art, Richard Cork appeared at the Venice Guggenheim in January of 2011 speaking on The Scandalous Epstein, a discussion of the sculptor Jacob Epstein. According to Cork in 1976, Vorticism was “an indigenous form of English abstraction,” which reacted to the age of machines, now dominating the world. But unlike the Futurists who were the midwives, so to speak, of Vorticism, the British artists did not worship the machine: they knew and feared it.

William Roberts. The Vorticists at the Restaurant Tour de la Eiffel, Paris: Spring, 1915

Before the arrival of the Futurists at the Sackville Gallery in the spring of 1912, the English art world enjoyed a comfortable art world, divided between the academic world of the tried and true old masters and the Pre-Raphaelites and the local proponents of Post-Impressionism, the Bloomsbury Group and the Camden Town artists. In terms of art, nothing of note was happening; in terms of literature, everything was pending with Virginia Woolf (1882-1941) three years away from publishing her first novel. But she was alert to the significance of the work of her colleague Roger Fry (1866-1934). In 1910 Fry mounted Manet and the Post-Impressionists at the Grafton Galleries and, in her essay, Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown, Woolf famously remarked ”On or about December 1910 human character changed.” She was comparing the pervasive mode for Victorian writing with the coming of a modern form of writing: ”Able by nature to spin sentence after sentence melodiously,” she wrote, ”they seem to have left out nothing that they knew how to say. Our ambition, on the other hand, is to put in nothing that need not be there. What we want to be there is the brain and the view of life; the autumnal woods, the history of the whale fishery and the decline of stage coaching we omit entirely.” Woolf’s comparison could be made not just between an old and new approach to writing fiction but also to the modern determination to sweep away the realist details of the visual arts to uncover something more essential and expressive.

In 1910, the Post-Impressionist exhibition at the Grafton Galleries work up the dormant art world. The horrified reaction of the Londoners over and exhibition of long dead artists well-known in France is both amusing and a measurement of how far out of step the art world in England had become. The London News was typical of the strong array of responses: “some who point the finger of scorn, some who are in blank amazement or stifle the loud guffaw; some who are angry; some who sleep.” The year 1912 must have been an even greater shock, given that the Futurists, famously provocative and confrontational, appeared in March and the year closed with Fry’s Second Post-Impressionist exhibition. Virginia Woolf, who stood strongly by Fry who faced scorn and ridicule recalled that “every now and then some red-faced gentleman, oozing the undercut of the best beef and the most succulent of chops, carrying his top hat and grey suede gloves, would come up to my table and abuse the pictures and me with the greatest rudeness.”

For the next two years, Futurism and Post-Impressionism, English style, co-existed in London, and while it was true that both movements were multimedia, involved with experimental literature, art and décor and fashion, they were poles apart, representing different centuries. Nevertheless the future Vorticist artists were nurtured in the Omega Workshops of Roger Fry, who worked with the London elite, redecorating their once-stuffy Victorian parlors with brightly colored fabrics and hand-painted furniture and light colors inspired by Post-Impressionist art. It is hard to imagine the strong minded Wyndham Lewis and the creative Edward Wadsworth (1889-1949) working in harmony with Fry, who was the undisputed boss; and, indeed, these artists were dismayed to find themselves in a collective where their work was not properly credited. It was an argument over credit for the work done for the “Post-Impressionist Room,” staged for the Daily Mail’s “Ideal Home Exhibition” in 1913 that caused the generational break.

Led by Wyndham Lewis (1882-1957), the disgruntled artists seceded from Omega and set up their own organization, the Rebel Art Centre, headquartered at a house on Great Ormond Street. Here gatherings were held, lectures were given, harangues were delivered, and, incidentally, some art was made by the breakaway artists, Frederick Etchells, Cuthbert Hamilton, Edward Wadsworth, Christopher Nevinson (1889-1946), and Kate Lechmere. Inspired by the Futurists, the Vorticists recognized the need to be of one’s own time but were uninterested in the Italians’ obsession with movement. The Futurists understood modernism through its manifestations, its toys, its objects, all the things that went boom and swoosh. The Vorticist artists understood the links between technology and the machine and mechanics and dynamism and knew that the force behind runaway unstoppable industrialization was energy. This energy, symbolized by the vortex, was caught in the dialectic between the lingering Victorianism that clung to England and the omnipresent force driving technological progress.

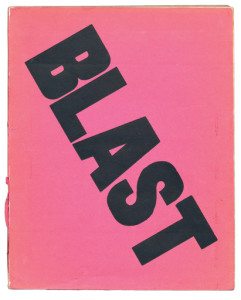

But the most remarkable artifact that emerged from the house on Ormond Street were the two issues of the publication, BLAST, in capital letters, like everything the Vorticists did. The magazine was published only twice, the first issue appeared on the eve of the War in July of 1914 and the second publication, the “War Number” came out a year later, announcing the death of the French sculptor, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1881-1915), one of the original Vorticists. Gaudier-Brzeska, like so many of the young men who went off to this War was killed at war in the trenches, dying of senselessness. The dual issues of BLAST railed against polite English society at a time when its traditions were dying in fields in Belgium and France and after 1915, the publication quietly closed and the artists, now scattered by the war, translated the vocabulary of Cubism and the lines of force borrowed from Cubism into the Vorticist language that could evolve from an edgy abstraction to a compelling picture of the Great War.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.