Matisse at War

The Dark Period, Part One

In the narrow confines of the world of the Parisian avant-garde, Henri Matisse (1869-1954) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) were well known rivals for the affections of art dealers and art collectors alike. Both were associated with art movements, a phenomenon new for the twentieth century in that these outbursts of assertive styles were small in the number of artists and captured the suddenly short attention spans of the art world only briefly. Matisse, the elder, was called the leader of the Fauves or the “wild beasts,” which had briefly prowled the galleries of the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne. Picasso was younger and more hungry for fame but had put his faith in an art dealer, rather than seeking notoriety in the Salons. Despite his low profile as an artist, Picasso was considered the leading Cubist, the new movement that had overtaken the Fauve phenomenon. Matisse, whose paintings before the Great War were brightly colored, scored with lyrical choreographic dancing lines, was not attracted to Cubism, which, with Picasso, was monochromatic and sharp edged, giving little pleasure to the viewer while demanding a great deal of tolerance. Matisse’s biographer, Hillary Spurling reported Matisse’s reaction to the work of Picasso: “Of course Cubism interested me, but it did not speak directly to my deeply sensuous nature, to such a great lover as I am of line and of the arabesque, those two life-givers.”

However, as Spurling recounted, the two artists began what would be a long term friendship in the summer of 1913. After nearly a decade of intensely productive work, Matisse laying the groundwork for his Fauve phase and Picasso moving quickly through a series of personal styles before Cubism, the artists were ready to move on and were wondering what their next moves would be. Picasso was on more secure ground that summer, being deep into collage and constructions, experimenting happily with mixed media. Matisse had settled into a comfortable relationship with the Russian art collector he shared with Picasso, Sergei Schuchkin (1854-1936), who was transporting their paintings to his villa (mansion) in Moscow. Both artists, however, wanted to move forward as individuals and detach themselves from their associated movements and the members. Both artists had become internationally well-known, having a strong presence in the increasingly important German (Berlin) art market, where Picasso was the new favorite, and they had been selected to appear in a very advanced exhibition site in a rather provincial setting, Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery. The Great War would interrupt the international exchange among artists when Germany went to war against France, Great Britain and Russia, cutting off Matisse and Picasso from their financial life lines and their most appreciative audiences. The unnatural interruption coincided with undercurrents in their work that would assert themselves during the War. Picasso had returned to color with his collages and his work during the War would abandon, once and for all, the old monochromatic pallet and revel in vibrant hues and vivid patterns. In a counter move, Matisse, the master of color, would spend the years of the War exploring dark and muted tones, especially grays and blacks.

The Great War changed the Parisian art scene, scattering many artists who would return four years later to realize that they had fallen behind the two men who did not have to serve in the military–Matisse and Picasso. Before the War, Picasso had been successful, thanks to his dealers, but his friends mostly lived in poverty until the War suddenly made turned the avant-garde into the heroic pre-war period of the avant-garde. A line had been drawn, hard and fast, in the historical sands. As if registering the end of an era, according to Dan Franck in his book, Bohemian Paris: Picasso, Modigliani, Matisse, and the Birth of Modern Art, the avant-garde artists began to leave Montmartre, suddenly a tourist attraction, and moved their headquarters to Montparnasse. As Franck described wartime Paris, the city was a depressing place:

Paris in wartime, Paris in poverty. The city was clothed in the dull colors of deprivation and restriction. The lamp-posts and the headlights of cars were dimmed. Shop windows were fitted out with anti-bomb tape. People had to get used to new rules. Hunger weighed like a leaden sky over the population..The war cut off the revenues of all the foreign artists living in Paris: the art dealers had left the city, the galleries were closed. The money that some of them regularly received no longer crossed the border.

Within a month, the War would become permanently stalemated and trench bound inside the border of northern France. For years, a war of mutual annihilation and attrition would drag on, draining France of its best and brightest, depriving it of an entire generation of young men, with losses to culture that can never be measured. However, Matisse’s venture into the dark paintings presaged the beginning of the Great War with his 1913 Portrait of Madame Matisse who had once dazzled with a green strip down her face, was now a sad hard gray mask and his Morocco series was notable for the unexpectedly astringent and dour colors. Writing for the Tate Museum, historian Juliette Rizzi, pointed out that these paintings were sharp and straight-lined, indebted to Cubism as if Matisse were paying a visit to the other side in order to see what he might harvest. Indeed the years of 1913 to 1917, ushered in an interim period of dark paintings that seem to have been a bridge to the style he would settle upon for the rest of his life, an approach he seemed to have found in the last year of the Great War. For Matisse, the War was a difficult period. As his avant-garde colleagues went off to war, one after the other, Matisse felt left out and patriotically attempted to enlist. At age forty-four, the artist was too old, his heart was bad, and so he missed one of the salient events of his lifetime, spending the War as an anxious spectator.

Although Matisse had left his home town, Bohain-en-Vermandois, a small city in Picardie involved in textile manufacture, and spent his adult life in Paris, his family remained in the border area, just inside the French border with Belgium. For French people, living in these border regions, the shadow of Germany always loomed. During the Franco-Prussian War, the battle of Sedan ended the reign of Napoléon III near the Prussian border and this region of Picardie was directly in the path of the German armies which deliberately invaded through Belgium and pressed into northern France. During the Franco-Prussian War, Bohain-en-Vermandois was captured, as it would be in 1914 and again in 1940. During the Great War, Picardie and the town of Bohain-en-Vermandois was caught up in this pocket of German advance into France, swelling towards Paris. It was here that one of the early battles of the Great War was fought, the Battle of Picardie during the days of September 22 to September 26. This battle was part of a larger maneuver by the French army–the Race to the Sea–and the French Second Army confronted the German First Army and pressed it north of Compiègne, the site where the Germans would eventually sign the surrender four years later. This territory was also the site of the future Battle of the Somme and the huge German guns gave the area tremendous pounding. A reporter for The Saturday Evening Post, of all publications, was on hand at Laon and wrote of the devastation wrought by the howitzer:

Then everything—sky and woods and field and all—fused and ran together in a great spatter of red flame and white smoke, and the earth beneath our feet shivered and shook as the twenty-one-centimeter spat out its twenty-one-centimeter mouthful. A vast obscenity of sound beat upon us, making us reel backward, and for just the one-thousandth part of a second I saw a round white spot, like a new baseball, against a cloud background. The poplars, which had bent forward as if before a quick wind-squall, stood up, trembling in their tops, and we dared to breathe again.

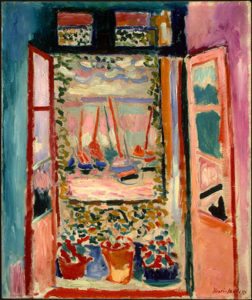

This then was the battleground within which Matisse’s family was trapped and would remain in place for four years. The Matisses could not get out and their famous son could not get in. To his distress, his younger brother was sent to a German prison camp, leaving their widowed mother alone and trapped in the family home. Later, Matisse’s sons, Jean and Pierre, would be drafted, adding to his helpless worry. All the artist could do was to produce a series of some fifty etchings, portraits, which he sold in order to raise funds for French prisoners of War. While pleasant and marketable, this etchings are not particularly significant works, but they are indicative of Matisse’s desire to contribute and participate in a war he could not fight in. One of the seminal works from his wartime period, French Window at Collioure of 1914 is a stunning contrast to his earlier painting of The Open Window a decade before in 1905.

One painting is brightly colored, fresh, full of air and sky. The window is open as if in invitation, beckoning the viewer to stand next to the row of potted flowers and gaze out to the vividly painted boats jostling on the pink waves. The second painting is deeply abstract, the French windows barely registering at the edges where muted blue and green rectangles tilt inward toward a total black expanse, which could be night, or it could be darkness incarnate. The same contrast can be seen in two paintings of goldfish, one of Matisse’s favorite subjects. One, Goldfish Bowl, completed in 1910 was a riot of joyous colors with orange goldfish darting about in a contained golden pond surrounded by green leaves. The only darkness is the black table, seen only in a corner, contrasting with a pink background, studded with dancing green activated dots of color, contrasting with the lazy fish. The second version the goldfish, dated six years later, Goldfish and Palette (1915) showed only two deep red goldfish, floating in a bowl of white water. But this painting is Matisse’s post-war flirtation with abstraction and is punctuated with a black band striping down, touching top to bottom, flanked by blue. The arabesques in this painting are wrought iron flourishes, carefully controlled.

A similar journey into more subdued colors also appeared in The Piano Lesson of 1916, showing the artist’s son Pierre working at the piano. Nicholas Fox Weber in his article, “What’s Wrong with This Picture?” young Pierre who was sixteen at the time noted that he was practicing the “sofa,” which was “the music scale and the four syllables of the tetrachord.” The teenager had to learn the piano, doing stultifying and boring lessons, and attempted to learn the violin too late in life to be proficient, attempting to emulate his famous father who had recently returned to the violin to sooth his war jangled nerves. Writing for The Guardian, Jonathan Jones noted that The Piano Lesson was painted the same year that the anti-art movement Dada was founded:

Greyness dominates and oppresses the picture, and it perversely demolishes pictorial logic, as a depressive mood might distort one’s sense of reality. Thus the same grey colours the view outside the window, the walls and floor of the living room, and even the torso of the woman on the stool – to the extent that it takes time to feel your way to seeing the room as a room, the window as a window. Only Pierre himself is a fleshy, human survivor of this miasma, along with tokens of life: the bronze nude in the corner, the candle on the pink piano top and, like a torch beam, the ray of green garden that cuts desperately across the grey world.

In the article “Lessons of War,” Jones continued, “And yet it was Matisse who created the most insidiously pessimistic painting of the 20th century: The Piano Lesson. In this completely unexpected painting, Matisse paints the death of his own art. Soon afterwards he left Paris, settling in the south and not really making a comeback until the end of the 1920s. It’s an elegy for a way of life, one that Matisse felt no longer made sense – even though in The Piano Lesson he offers a last, desperate justification for the French bourgeoisie.” Much has been read into the paintings of Matisse during the first three years of the War, but when discussing Gourds (1916), the artist did not recall despair or elegy. Instead he explained that the use of black was intended “as a color of light and not as a color of darkness.” In its own way, The Piano Lesson, eight feet tall, has its bright moments, the geometric areas of green and red, contrasted by a streak of pale orange. Pierre’s bobble head is pale pink shaded with a shard of the same orange. See in situ, at the Museum of Modern Art, this painting is far more painterly than its graphic qualities would suggest, reminding the viewer that Matisse was a very tactile painter who enjoyed moving paint about.

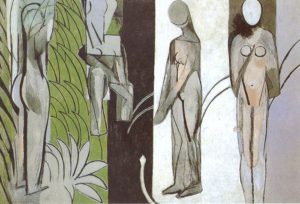

The deeper toned paintings continue to dominate Matisse’s work, but far and away the best know of the works of this period, were exhibited at the recent exhibition, Matisse: Radical Invention, 1913-1917 at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2010. Bathers by the River reached its finish in 1916 after years of working and overworking, an series of active intervention on the part of Matisse, who, uncharacteristically, scratched and gouged and punched the surface. He began this painting in 1909, then returned to it in 1913, and finally found the final form between 1916 and 1917. The scrapings revealed the previous and more colorful version of the five bathers in their original brightly colored setting. For some reason, Bathers challenged Matisse, and recent X-ray analysis revealed no less than seventeen transmutations of color. In its final and restrained state, the large painting, dominating in its imposing size, moves from left to right: the bather begins in a forest of green, broken with the now characteristic band of black, leaving the other two bathers stranded on a band of white and a band of blue, signifying the river itself. The bathers are strongly and plainly drawn with great assertion and assurance, as Matisse moved away from curved lines and bright colors and the sheer “bonheur de vivre” so evident in his earlier works.

It can be debated if the dark muted paintings of those four years are related to the Great War, whether sensing its nearness in 1913 or expression the fear and apprehension that descended upon France. When the Bathers was being completed, the Battle of the Somme was underway, putting Matisse’s family in even more danger and continuous danger as the Battle dragged on month after month. Ironically, the safety of his elderly mother depended upon the kindness of the German army which occupied Bohain-en-Vermandois. Art historian John Elderfield explained the these wartime works were done in a period that was “like a black hole in his career.” And the oeuvre created by the artist during the debacle on the Western Front was a substantial one and yet as Elderfield pointed out, it has been overlooked in favor of the received version of Matisse “as an artist of hedonism and luxury, because nobody had seen these pictures.” In fact few of them were exhibited before 1966, suggesting that Matisse might have understood the phase of his career as transitional or experimental. Whatever his state of mind, it is clear that this phase is often neglected, as many historians jump directly to the year 1917, when, as if he can take the darkness no more, Matisse decamped to Nice, where his art changed once again, because, as he explained, “A will to rhythmic abstraction was battling with my natural, innate desire for rich, warm, generous colors and forms,” an apparent to form that will be discussed in the next post on Matisse during the War.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.