Italy at War

The Futurists Fall

When Filippo Tommaso Emilio Marinetti (1876-1944) called for “war” in his famous Futurist Manifesto of 1909, he was not asking for actual war, as in clashes between nations. The poet was demanding a rebellion against the status quo, an uprising of downtrodden classes, and a recognition that the past was the past–over and dead–and a demand that the future would be acknowledged. For Marinetti, the future was present; it was here, but the future needed to be grasped. Marjorie Perloff, Futurist expert, pointed out that the his “movement” that required a “manifesto” to explain was first called Elettricismo or Dynamism, stating the the poet was demanding a “utopian cleansing,” or a new way of life for the future. The distinction between “Futurism” and its two earlier names was significant, not because Marinetti eventually decided upon “Futurism” but because these early names indicate that, for him, the metaphor for the future was the machine, that which was unnatural and mechanical and inhuman. The dynamism (Dynamism) of the rapidly moving machine, frequently powered by electricity (Elettricismo) which was systematically lighting up the big cities and powering industry was a signifier of the future, for all things to come. The question faced by Marinetti was how was the “future” to be acknowledged?

The question was not an insignificant one was Marinetti was writing and thinking out his ideas in 1908. The beginning of the twentieth century had come, not with a bang but without much ceremony and Europe continued its long lingering romance with the nineteenth century. This romance had to do with the determination to hold off progress and to maintain things as they were. The lower classes were restive and women were becoming annoying in their demands for political and social rights. The upper classes, upheld by their lands and rents, faced newly powerful people without pedigrees who had become rich, nouveau riche, through trade, business and industry. As Cinzia Sartini Blum explained, “At its inception, Futurism was a reaction against the fin-de-siècle malaise that took the form of a pervasive sense of a dislocation in the logical, causal relationship between past, present, and future. Marinetti’s antidote to the ills of modern decadence is the formulation of a mythical new subjectivity that rejects the limits of history and empowers itself by appropriating the marvels of technology to create a utopian Futurist wonderland infused with primal life forces.“

Centuries old traditions were threatened and the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth century were years of a Götterdämmerung for the upper classes. Marinetti’s irritation and his subsequent strident poetic bombast selected his impatience with the social lag in the face of technological advances, accounting for his excitable utterances. Of particular fascination to historians after the Great War was the Futurist appetite for war–or Marinetti’s apparent longing for war. In article 9 of the Futurist Manifesto (1909) its author Marinetti famously wrote, “We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.” He continued,

For us today, Italy has the shape and power of a fine Dreadnought battleship with its squadron of torpedo-boat islands. Proud to feel that the marital fervor throughout the Nation is equal to ours, we urge the Italian government, Futurist at last, to magnify all the national ambitions, disdaining the stupid accusations of piracy, and proclaim the birth of Pan-Italianism. Futurist poets, painters, sculptors, and musicians of Italy! As long as the war lasts let us set aside our verse, our brushes, scapels, and orchestras! The red holidays of genius have begun! There is nothing for us to admire today but the dreadful symphonies of the shrapnel and the mad sculptures that our inspired artillery molds among the masses of the enemy.

The prevailing ideas of Futurism were war and power or power and war, which should be read in the original context as a call to what we might terms “power to the people” to go to “war” with the status quo through change as symbolized by the dynamism of the machine. Technology was a force that could not be denied. The concept of the internal power of technology was a new one at the beginning of the twentieth century and it would be decades after Marinetti when a modern understanding of technology emerged. The most famous discursive trope of “technique” was developed by Jacques Ellul in The Technological Society (1964). He argued that technology or “technique” functioned according to its own laws, speeded or slowed, its direction shaped by its own inner logic. Although technique was cultural, it too had its own “natural” laws of development and would proceed in unforeseen directions, building part upon part, discarding what was not needed or was suddenly obsolete, and engaging in what a twenty-first century observer would term “creative destruction.” Although it is anachronistic to apply such a phrase to Futurism, the words give a sense of what Marinetti was sensing–a relentless and inhuman pressure building up and eroding history. “Creative destruction,” then, was this poet’s “war.”

But Futurism and its bellicose attitude towards an unbearable present and an overbearing past was not a novel phenomenon in Italy: the movement came out of a context that had been expressing the same frustration for years. It is only its art that eventually made Futurism into something unique when the sentiments put forward by Marinetti as part of a national discourse become disseminated internationally. Giovanna Amendola wrote in La voce at the same time Marinetti was thinking of his new manifesto,

Dissatisfaction and intense bitterness, still infused with too much inertia and skepticism, fills Italians who are not approaching thirty..Disgust and pity fills us when we look back over the past decades political and administrative life in our kingdom and see how they have been irremediably stamped by moral deficiency and intellectual poverty of our ruling class..With implacable intransigence we have to say No! to the present state of affairs, if tomorrow, with inevitable compliance, we want to say Yes! to our aspirations.

In his important book, Futurism and Politics: Between Anarchist Rebellion and Fascist Reaction, 1909-1944, Günter Berghaus connected Futurists to these attitudes by saying that “Among this interventismo rivoluzionario, designed to fulfill the visions of the risorgimento that had faded in the post-unification era, we find the Futurists and the chief ideologues the later Futurist movement. Their theory of a guerra buona, that is, of war as revolution..” Ironically, when the actual Great War finally made its inevitable entrance, “the technological society” and the internal logic of change made itself manifest in a crazed and destructive development of deadly weapons. But the Futurists, or those who wanted a “real” war in the hopes that such an event would be properly cataclysmic and end the old world–which it did–would have to wait. Italy was historically aligned with Germany but had no intention of siding against England and balked at entering a war of aggression on the side of the aggressor. If there was a propaganda war fought in August and September of 1914, then Germany lost and Italy was its first casualty. Italy hovered at the brink of war, looked at the abyss and waited, biding its time.

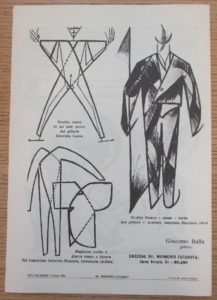

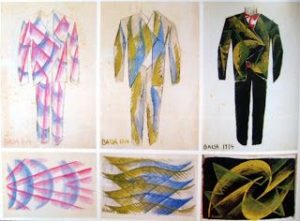

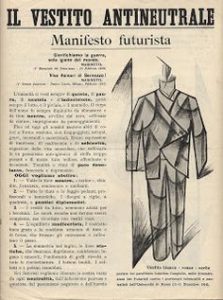

The Futurists reacted to the Italian position of neutrality with anger. Despite his international celebrity, Marinetti was a strong nationalist and wanted Italy to join in immediately and come in on the side of France and England. This nationalism drove the poet and the Futurists to take an “Interventionist” position, insisting that Italy intervene, enter into the fray, and Marinetti missed no opportunity to make his position known, designing “The Antineutral Suit” with Giacomo Balla (1871-1958).

Giacomo Balla and Filippino Marinetti. The Antineutral Suit (1914)

Marinetti’s allies, such as Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916), who burned an Austrian flag in a Galleria, and composer Francesco Balilla Pratella composed a “Hymn to War,” and Carlo Carrà composed his famous Interventionist collage, were all part of the Interventionist movement, along with Benito Mussolini, an up and coming politician, who was expelled from his party for his position. It was at this transitional time, Futurism was gathering new recruits, such as Mario Sironi and Fortunate Depero who worked with Giacomo Balla on “plastic complexes,” while Marinetti was increasingly involved in political theater. The outbreak of the War had disrupted the Futurists trajectory in the international art market, cutting them off from one of the more receptive sites, Russia, and a growing art market in Germany. Now the group, largely congregated in Milan, was distracted by the Interventionist movement and nationalist designs, underscoring the fact that Futurism had long been a political movement bent on agitation and disruption.

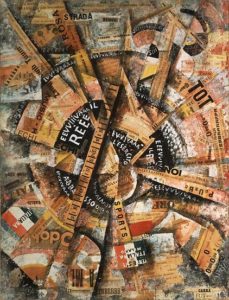

Carlo Carrà. Interventionist Demonstration (1914)

When Italy finally entered the war in 1915, it was on the side of the Allies and Italian artists participated in an effort to mobilize public opinion against Germany. The tool they used were posters and postcards, mass distributed propaganda, depicting the Germans as being greedy for power and empire and encroaching upon the territories of others. For Italy, with its history of designs upon African territories, Eritrea, Libya and Ethiopia, it meant drawing a fine distinction between “legitimate” Empire and irresponsible aggression. Günter Berghaus noted that Italy longed to be a first rate power, and at the end of the nineteenth century, first rate powers had empires. He described the nationalism that emerged from this fin-de-siècle period as “an aggressive, bellicose, chauvinistic, imperialistic nationalism.” It was this attitude that fueled Futurism and it was this mindset of thwarted ambition that made it relative simple for Italy to change sides for its own self interest. As Ana Antic, in her article on “First World War Postcards” explained,

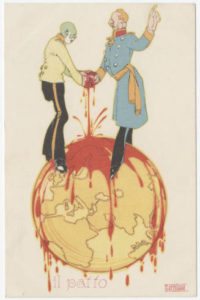

Interestingly, while WWI marked the failure of nineteenth-century liberal internationalism, it was also the origin of a new and highly ambitious concept of ordering international relations. In a series of Italian postcards from WWI, several cartoonists and painters, such as R. Ventura and Aurelio Bertiglia, articulated this profound disappointment with some of the predominant agents of internationalism at the time, and used the image of the globe in imaginative, sarcastic and unusual ways in order to reinforce their political message. These postcards were an essential part of WWI political propaganda, and contributed to the extremely extensive propaganda campaigns undertaken by the Entente governments to discredit German military conduct and involvement.

Largely agricultural, with conflicting dreams of empire inspiring it to take on ill-advised adventures, the nation was distinctly unready to enter into a massive conflict and held back, as if asking what was in it for Italy? First and foremost, Italy could go to war with its historic enemy, the Austro-Hungarian Empire with which it had territorial disputes. Being, hopefully, on the winning side of a global war meant that Italy could lay claim to parts of the Empire to the north, an empire that was unlikely to survive the War. Given that Italian males had acquired suffrage in 1912, it was necessary to persuade these new voters that a such a war was a just one and one worth participating in.

As Antic wrote,

The first postcard, from about 1914, depicts a ‘bloody handshake’ between the leaders of two Central Powers: Austria-Hungary’s Franz Joseph and Germany’s Wilhelm II. It is captioned ‘The Pact’, and uses the globe to articulate a pithy critique of the German- and Austrian-led attempts at (re-)ordering the international affairs: through their particular vision of internationalism, the Habsburg Emperor and the German Kaiser have plunged the entire world into a bloody conflict. The alliance between the two powers is then held solely responsible for the outbreak of the conflict, and their incompetent leadership as well as the malicious effects of their political friendship are exposed to ridicule and contempt.

This postcard, one among many of its kind, is instructive, because the image involved a delicate but decisive severing of Italy’s connection to the Triple Alliance, which included the Empires of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Once again, Italy, haunted by memories of the Roman Empire, wanted the bordering territories of Dalmatia, Trieste and Istria and it was with these hopes that they joined the Triple Alliance in 1882. After a long wooing to persuade Italy to give up its position of neutrality, these territories were the prize that was promised Italy by the Allies, and the homeland of Marinetti and the Futurist artists finally entered the War on May 24th. For the Italians on the Eastern Front, the war quickly bogged down into a position war, or “guerra di posizione” known as trench warfare on the Western Front. For the next two years, glory eluded Italy and whatever dreams or fantasies the Futurists may have harbored about the capacity of War to bring change were bogged down in trenches.

But what of the Futurist artists? Strangely, given their fascination for machines, they did not volunteer to fly planes or man machine guns or to guide artillery pieces, instead these warriors from the future joined the Lombard Battalion of Volunteer Cyclists and Motorists. Many of these battalions were know to be both patriotic and interventionist and seemed to offer a congenial home for the Futurists. As Selena Daly wrote in her article “The Futurist mountains’: Filippo Tommaso Marinetti’s experiences of mountain combat in the First World War,”

Prior to Italy’s entry into the First World War in May 1915, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of the Futurist movement, and a number of other prominent Futurists had enrolled in the Lombard Battalion of Volunteer Cyclists and Motorists. Alongside Marinetti were the painters Umberto Boccioni, Luigi Russolo, Ugo Piatti and Mario Sironi and the architect Antonio Sant’Elia. In the summer months of 1915, the Volunteer Cyclists received training in Gallarate, near Milan, before leaving for Peschiera on the southern shores of Lake Garda at the end of July. In mid-October, the battalion was sent to the Italian-Austrian front line and stationed at Malcesine, on the eastern side of Lake Garda. The Volunteer Cyclists’ principal experience of combat was in the capture of Dosso Casina in October when they fought alongside the elite Alpine soldiers. Their experience of fighting on the front line was destined to be short-lived, however. By the beginning of December, the Battalion of Volunteer Cyclists had been disbanded. So the Futurist volunteer cyclists returned, at least temporarily, to their pre-wartime pursuits in Milan, although they ‘anxiously await[ed] the pleasure of returning to battle,’ according to Marinetti.

Umberto Boccioni, however, did not stay with the valiant cyclists and joined an artillery unit in July 1816, presumably to see more action, or at least a more modern war. It is unclear if he were the best of soldiers for he was offered release but he refused and continued to serve. Again it is interesting to note that this Futurist created a fanciful calvary charge in 1915, the kind of action that was both suicidial and rare in the Great War. This painting would be one of his last works of art.

Umberto Boccioni. Charge of the Calvary Lancers (1915)

Between the bicycle and the horse, there seems to be some distinctly unmodern nostalgia for an old-fashioned war. Marjorie Perloff quoted Boccioni from his diary as being disillusioned, writing, “I shall leave this existence with a contempt for all that is not art. There is nothing more terrible than art. Everything I see now is on the levels of games compared to a good brushstroke, a harmonious verse or a sound musical chord. By comparison everything else is a matter of mechanics, habit, patience of memory. Only art exists.” His life was soon over in a sad twist of fate described by Rosalind McKever in her article in Apollo, “Harnessing the Future: The Art of Umberto Boccioni,”

During cavalry exercises on 16 August his horse was spooked by a lorry and bolted. Boccioni fell and was dragged by the horse, suffering severe injuries and dying only the following day. Throughout his career Boccioni had painted horses and it is a cruel irony that, having named his steed Vermiglia after the flaming red beast in the centre of The City Rises (1910), his fall would imitate the scene of what has become his most famous painting.

Boccioni’s War Diary (1915)

It is ironic to note, in passing, that the last great Futurist exhibition was held, not in Europe, but in America at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in 1915. Both Italy and America were natural at that time, a position Marinetti rejected, but nevertheless, working with J. Nilsen Laurvik, a Norwegian specialist in the international avant-garde, he arranged for fifty Futurist works to be shown in San Francisco. Two years earlier, Futurism had not been exhibited at the better known Armory Show in New York City in 1913. There were “futurist” artists in New York, speaking for Futurism, but it was Cubism that was called “Futurists” by the natives who thought any modern art was from the future. It was at the PPIE, however, that Americans, at a time of war in Europe, were able to visit the remarkable assemblage of Futurist paintings and sculptures, including works from Hungary, Austria and Italy all of whom were fighting each other. However, this exhibition has become a mystery in its own right. As curator Gergely Barki, who specializes in Hungarian art, stated,

50 Italian Futurist paintings exhibited at the event. On this photo you can count 14 paintings and a sculpture, but we know only one of the paintings. Only 10 percent of the entire material has been credibly identified, which means that, at the moment, nearly 40 (!) Italian Futurist works are missing, that is, lurking and waiting for identification. As far as we know, the collection was sent back to Europe in 1916, after the world’s fair, but if so, then why don’t we know these works? The mystery is further enhanced by the fact that a few previously unknown works that were nevertheless certainly exhibited at the PPIE have popped up in the United States, including the one identified Giacomo Balla painting which can be seen on the photograph I’ve just mentioned and which has not been exhibited at any other event in the past 100 years.

Futurist Room at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in 1915

The next post will discuss other Futurist artists and their work during the Great War.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.