Futurism in Transition

From War to Fascism

The Great War did not go well for the Italians. Aside from the enthusiastic Futurists and their nationalist sympathizers, such as Benito Mussolini, most Italians regarded the war with wary eyes. The nation had to be bribed into the war by the Allies who promised Italy not just territories that were “lost” to the Austro-Hungarian Empire but also were given “permission” to add to their African territories and could help carve up the Ottoman Empire. One could say that Italy had driven hard bargain if the promises were possible to fulfill–but that outcome was in the future. The two solid years of causalities and deaths on the Alpine Front cost the nation over a million lives and that figure referred only to the slaughter on the Isonzo River plain, the Carso plateau. There was another site of death for the Italian army and that was the nearly forgotten “White War.”

The Alpine Front amounted to a third front which wended its torturous path from the Julian Alps to the Ortler massif to the Adriatic Sea, a line of over 250 miles. When the collective memory considers the Great War, it is the muddied fields of Flanders that come to mind, but the Italians and the Austrians were fighting in the mountains over disputed territories that lay between the two powers. These age old enemies, which once had the relation of occupier and occupied, faced off against each other in what was a war of mutual mass destruction. In his eloquent book of 2008, The White War: Life and Death on the Italian Front 1915-1919, Mark Thompson recounted remarkable instances when the Austrians, sickened by slaughter warned their Italian counterparts to not advance, to not run towards the very mechanisms of death so admired by the Futurists:

On one occasion, the Austrian machine gunners were so effective that the second and third waves of Italian infantry could hardly clamber over the corpses of their comrades. An Austrian captain shouted to his gunners, ‘What do you want, to kill them all? Let them be.’ The Austrians stopped firing and called out: ‘Stop, go back! We won’t shoot any more. Do you want everyone to die?’ The author continued making the point that no where on the other Fronts did such events take place. “To take their measure, bear in mind that there was no shortage of hatred on this front, that soldiers could relish the killing here as much as elsewhere, the Austrians were outnumbered and fighting for their lives, and any officer or soldier caught assisting the enemy in this way would face court martial. These deterrents could be overcome only by the spectacle of a massacre so futile that pity and revulsion forced a recognition of oneself in the enemy, thwarting the habit of discipline and the reflex of self-interest.

Much of the Italian experience in this war was not just on the relatively flat plain but within the Alps themselves, or that stretch of the Alpine range called the Dolomites in the northeast of Italy. Once can attempt to envision a vertical war, some 6500 feet above sea level, a never-ending struggle encased in many, many feet of snow, carved out the ice and blasted out of rock faces. The weapons were then same as used on the plateau but they had to be hauled up slopes so angled that they defined mules or horses. Only humans, not well versed in the now familiar sport of mountain climbing, would traverse these mountain faces and they could not carry a cannon. Heavy equipment was hoisted upward by ropes and when fired, the cannon, would cause a shattering sound as the explosions, contained in the encircling peaks, would reverberate and echo. The cannon fire was often not directed against the other side but was used as noise, a noise so loud that it caused avalanches, burying troops by the “White Death,” so deeply that they were unrecoverable. This ninety degree war in the mountains would have an unexpected outcome. When the war finally ended in 1918, the Austrians and the Italians simply abandoned their aeries and went home, leaving the war and its detritus behind, including bodies of the dead, submerged in the snow.

Writing for The Telegraph a hundred years later, in an age of Global Warming, Laura Spinney explained, “As much of the front was at altitudes of over 6,500ft, a new kind of war had to be developed. The Italians already had specialist mountain troops – the Alpini with their famous feathered caps – but the Austrians had to create the equivalent: the Kaiserschützen. They were supported by artillery and engineers who constructed an entire infrastructure of war at altitude, including trenches carved out of the ice and rudimentary cableways for transporting men and munitions to the peaks.” Then in the early 2000s, the ice began to melt. Michele Gravino, for National Geographic wrote,

Italian and Austro-Hungarian troops clashed at altitudes up to 12,000 feet (3,600 meters) with temperatures as low as -22°F (-30°C) in the Guerra Bianca, or White War, named for its wintry theater. Never before had battles been waged on such towering peaks or in such frigid conditions..Entire villages of shacks were built, though officers generally lived in old mountain refuges, some outfitted with grand pianos and gramophones. On Marmolada, the highest mountain in the Dolomites, the Austrian Corps of Engineers built an entire “ice city”—a complex of tunnels, dormitories, and storerooms dug out of the bowels of the glacier..Now, a century later, the warming world is revealing the buried past, as relics and corpses are melting free of their icy tombs.

Most of the 150,000 dead in the Dolomites were from avalanches, frostbite and causes other than traditional battle wounds. Now one hundred years later, with the dead returning, demanding to be named, and needing to be returned to surprised families to be buried. For the Italians, the First World War, even with its catastrophic defeats, was a better war compared with the Second World War, which is tainted with the history of Fascism and Mussolini. In the book Italy’s Divided Memory, J(own) Foot noted that archaeological reclamations on the Carso plateau, revealing trenches cut from “hard stone.” He wrote, “In the areas of the ‘white war,’ the rapid melting of glaciers revealed a series of structures that had been built in tunnels within the ice..Global warming threw up some surprises. In the mountains above Val Rendena in Trentino, excavations began in 2007 into a frozen cave known as the caverna di caveat. This cave had been occupied by both the Austrian and Italian armies during the war.”

For Italy, it was a long strange war. But that was the war the Futurists demanded. In the strange year of 1915, while the nationalists and interventionists were marching for war, Giacomo Balla (1871-1958) painted a series of semi-abstract works, depicting crowds acting en masse. For Mussolini and Marinetti, the “crowd” was a mystical and mythical being, feminine, in its penchant for being malleable, moulded for any cause. Balla’s depictions of crowds reflected the events in Italy when the demonstrators would wave the flag of the House of Savoy–“Savoy” would become the battle cry that would lead the soldiers into battle. In 1911, Gustave le Bon wrote Psychology of the Masses, a book that would become something of a Bible for the Fascists, because the crowd, under the correct circumstances and with the right leader, could dominate. Le Bon described the “crowd” as “under these circumstances, the gathering of people possesses new, completely different qualities form the qualities of single people who form this gathering. The conscious personality fades, the feelings and thoughts of all the individuals are oriented towards the same direction.”

Giacomo Balla. Patriotic Demonstration (1915)

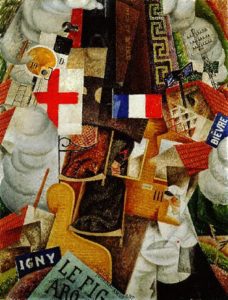

Meanwhile Gino Severini (1883-1956) was in Paris, watching an actual war unfold. Because he could view the Denfert-Rochereau station from his apartment in Paris, Severini was apprised of the comings and goings of troops and the constant arrival of the wounded from the Front. The Hospital Train of 1915 would have been a common sight. As the corner of the newspaper Le Figaro would indicate, the press would report on the long journey the trains would take from the aid stations at the Front to the hospitals in Paris. When the trains arrived in the various stations, the wounded would be unloaded and volunteer nurses, pictured by Severini, would offer water and care to the wounded. We discern this process through the red cross, the train smoke, and other details which from a composite collage like “idea-image.”

Gino Severini. Hospital Train (1915)

Gino Severini. Hospital Train Passing a Village (1915)

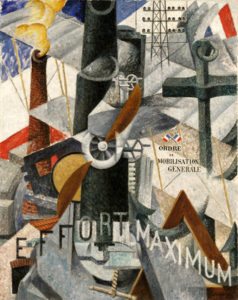

In light of the seriousness of the sight of the hospital train and its passengers, a similar topic, Hospital Train Passing a Village, is a reminder that Severini was always a painter of pleasant things and that he was probably ill-suited to the task put to him by Marinetti. The painting is simply silly, better suited for a child’s book on the war than for the adult audience which would be jarred by the jolly colors. In comparison to this rather illustrative and imaginary work, Virtual Synthesis of the Idea – War (1914) is darker in tone, combining elements that would appear in another painting of a similar name in 1915. Severini used Marinetti’s “words in freedom” unfailing near the bottom, referring to the “Maximum Effort” that would be needed to repeal the Germans. What is interesting about these two paintings is the extent to which they are not Futurist, not about speed or change or dynamism. Instead the paintings are static and immobile, composed of stacked elements, typical of Cubism.

As a painted collage, Plastic Synthesis of the Idea of War (1915) was successful for it at least captures some of the seriousness, from the reference to the mobilization order to the artillery and the airplane and so on, Severini combined, in a coherent fashion, his reaction to war, focusing on its technology and mechanization, eliminating the human factor.

![2 T UMAX Mirage II V1.4 [2]](https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/016seve-249x300.jpg)

Gino Severini. Plastic Synthesis of the Idea of War (1915)

Given the success of Christopher Nevinson in rerouting Futurism towards paintings of the Great War, the awkwardness of the actual works by the founding Futurists is a surprise. Severini’s sketch of Lancers, mirror that of Boccioni in its lack of comprehension of the fact that the calvary charge was a historical memory, unfit for modern war. Equally questionable are the static reactions to a war that was admittedly static by both Severini and Carlo Carrà (1881-1966). The stilled nature of the works, compared to the mobilized imagery by Nevinson, seems to be connected to their use of words and letters which tend to not activate the surface but fix it in place.

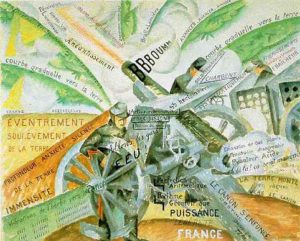

Gino Severino. Gun in Action (1915)

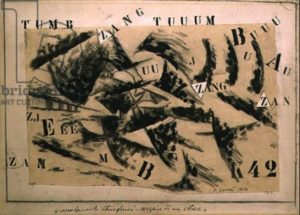

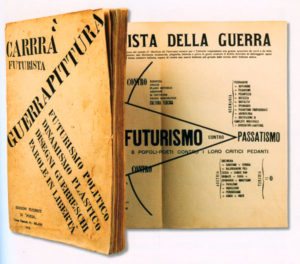

Severino’s Gun in Action of 1915 is simply wooded compared to Christopher Nevinson’s powerful and iconic La Mitrailleuse of the same year. It is no accident that Apollinaire praised Nevinson and apparently said nothing of Severini, who was, to be fair, hampered by his illness and could have had no comprehension of what it meant to be on an artillery crew, like Braque. If Severini’s paintings done during the Great War show his individual ambivalence about Futurism and reveal his long time affinity with Cubism, then it can be suggested that it was his distance from Futurism central, Milan, limited his full incorporation of Futurist aesthetics or purpose. But it was not just Severini for whom the War caused an artistic crisis. Carlo Carrà’s Guerrapittura of 1915, a virtual copy of an idea pioneered by Marinetti in his work Zang Tumb Tumb (1912) composed for the Balkens prelude. Combining words and abstract forms, Atmospheric Envelope-Exploding Shell of 1914, Carrà did a number of collages, combining words, drawings and pasted paper, more in the style of Braque, rather than Picasso. As these collages make clear, he was struggling with the language of Futurism. In his article, “Carlo Carrà’s Conscience,” David Mather would describe the emotional and artistic crisis faced by Carrà.

Carlo Carrà. Atmospheric Envelope-Exploding Shell (1914)

Carrà, as was discussed in a previous post, worked closely with Marinetti. Along with Boccioni, these Futurists were enthusiastic supporters not just of entering the War but also of what Intervening meant–nationalism, the kind of nationalism that would become fascism. Indeed on the fifteenth the November of 1914, Carrà wrote about Mussolini, an individual in whom “resides the drama of our whole generation. We admire him if for nothing else, then certainly for the courage that he keeps demonstrating.” While the War and military service was, for Carrà, a theoretical prospect. Mather quoted from a letter the artist wrote to Ardengo Suffici at the end of 1914, in which he longed for “the real war–made of blood and heroism.” The collages he created for his book on war–his response as an artist–were also theoretical, a standpoint taken in his concluding essay, “War and Art,” which, as Mather said, “characterized war as an engine of new sensibilities closely allied with, and even emerging directly from the futurist movement.”

Carlo Carrà. Joffre’s Angle of Penetration Against Two German Cubes on the Marne (1915)

The Great War did not, of course, come from Futurism and Carrà would be confronted with the disconnect between the idea and the reality. This series of collages in Guerrapittura was not only a turn towards Cubism, also evident in the work of Severini, marked the end of Carrà’s time as a Futurist. Drafted in1917, he went to war, proved to be unfit for battle, and found himself in a hospital where he met Giorgio de Chirico (1888-1978), who was working in the military hospital at Ferrara. As with the other Futurists who served in the War, Carrà found the actuality of fighting in trenches disconcerting. After all, he was a nationalist and a revolutionary, not a soldier.

It is possible, as Mather suggested, that Carrà’s conversion to Metaphysical Painting was the result of the trauma of the War, but he continued to support nationalism, even though he knew the reality of combat, and retained his devotion to Mussolini. As for Sererini, he, too, moved away from Futurism and Cubism, and, like Carrà became part of the post-War “return to order,” which, for these artists, would be a new form of classicism. The arc of the Futurism of the founders was a short one, with the energy and ideals drained away by the Great War. But Futurism was not dead. As was noted in a previous post, during the War years, new members joined Futurism and would carry Futurism on into the rest of the twentieth century. The new phase of Futurism would focus on the new technological hero that emerged during the Great War, the airplane, the machine that could fly and give the women and men who flew it wings.

The Great War ended disastrously for Italy. The military suffered 2,197,000 casualties, of which 650,000 died–or so say the official figures. For a nation that went to war on the promise of booty, the recovery of territories considered “Italian,” these losses had to count for something. Although they had been on the winning side, their War ended in a “mutilated victory.” However, at the Treaty of Versailles in the spring of 1919, the other allied nations made it clear that, in their opinion, Italy had not done its fare share and and not fulfilled its promises as a military partner. The Italian delegation was treated with contempt by the British and the French, while the Americans wanted to give Italy as little as possible. The Italian government was supported by the nationalists only and the nationalists wanted what was promised in the Treat of London plus the Adriatic port city of Fiume. However, a new player was on the field, America, and President Woodrow Wilson represented the new approach to diplomacy, ethnic and self-determination as opposed to the system of spoils. The Italians considered the Treaty of London to be binding, the Allies considered the Treaty an obstacle to be overcome. To the consternation of Italy, a new nation, on its borders, was carved out the the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Yugoslavia, including territories claimed by the Italians, especially the city of Fiume. In the end Italy was placated, possibly because British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour said, “The Italians must be mollified, and the only question is how to mollify them at the smallest cost to humanity.” In the end, Italy received a seat on the League of Nations, a share of German reparations and the Tyrol. The nation of Italy was deeply angry at the way it had been slighted and, despite the warnings of the delegation that such disparaging treatment only incited radical political forces, such as the fasci di combattimenti. Their warnings went unheeded and it was at the Treaty in Paris that the seeds for Italian Fascism was planted and the foundation for the rise of Mussolini was laid. For the Fascists, the humiliation in Paris had to be avenged.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.