Futurism in Transition

From War to Fascism

Although in the histories of the Great War, Italy is usually written of as a “minor power,” or a minor player in the larger structure of the War. The nation was a latecomer to the conflict and had limited goals. Italy had not been invaded and there were no enemies rampaging through Italian fields and towns. Indeed, there seems to be little reason for Italy to enter into a war that, by 1915, was showing signs of being long and bloody and inconclusive. But, from the Italian point of view, there were against to be made. For decades during the nineteenth century, Italy had struggled to become an independent strong united nation and was thwarted at every point by the Austro-Hungarian Empire which had historically dominated and occupied northern Italy. When Italy finally unified–Italian Risorgimento–Italian unification–in 1861, far too much of ethnically Italian territory remained in the hands of the Austrians. The new nation had pried Lombardy from Austria and, eventually, was awarded Venice for siding with Prussia during the Seven Week’s War in 1866. Longing to retrieve the rest of its “lost” territories, Italy joined with Germany in the Triple Alliance on the hope that Austria would stop its attempt to grab land and that it would be protected from the Empire. In 1915, Italy entered into a secret agreement, the Treaty of London, in which it was agreed that it would enter the War on the side of the Entente Cordiale and receive in return Trento and the South Tyrol as far as the Brenner Pass, along with Trieste and the Austrian Littoral as well as northern Dalmatia, the so-called terre irredente (unredeemed lands), after the War was successfully included. The assignment given to Italy was to open an Eastern Front along the southern border of the crumbling Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The role Italy played in the defeat of Germany (and Austria) is often considered a side bar to the major action of the Western Front, but aside from confronting the enemy directly, one of the most important moves an adversary can make is to attack from the rear and force the enemy to open a new front. This new front, however, was complex. It was necessary for Italy to attack Austria, win quickly, and seize the advantage before Germany could react and come to the aid of its ally. There was another reason to move quickly–Futurists not withstanding most Italians were not entirely enthusiastic about going to war. The government could count on a brief burst or nationalism and patriotism but not on public patience for a long war. But geography in this alpine region was all but impossible. The border, disputed or not, between Italy and Austria, ran through the Dolomites and Carnic Alps, a nearly impassable mountain range unsuitable for modern warfare if one needed to make a quick breakthrough. There was only one place that seemed to be flat enough, the plain around the Isonzo River and it was here that the Italian high command chose to strike. In the early days, the commanders did not believe that their front lines would become stalemated, but they were wrong.

The Italians did not declare war on Germany right away, after all the Austro-Hungarian Empire was the main enemy and the prime goal was territorial. Therefore it was not until 1916 that Germany could intervene when Italy intervened and attacked Austria. From the beginning, Italy was on the offensive and the Austrians on the border were forced on the defensive, waiting for reinforcements. That said, the Austrians were dug in, with fortifications on the high ground, in the mountains above the river plain and the Italians mounted no less that twelve battles, all named the “Battle of Isonzo.” The commander in the region, the Italian Chief of Staff, Luigi Cadorna, initially made some advances but could not capitalize on any gains and the War on this front soon bogged down–literally for there were record rainfalls during those years–into trench warfare. In his book, The Italian Army of World War I, David Nicolle wrote, “Even though Cadorna soon realized that this was going to be a war of attrition, he continued to have faith in massed artillery and massed infantry attacks.” However it was not until the costly Battle of Caporetto (the Twelfth Battle of Isonzo) in 1917, with the loss of 300,000 casualties, that, as Nicolle continued, “The Italians were aware of the shortcomings which had exposed them to defeat at Caporetto, and the first half of 1918 was dedicated to changing the army’s outmoded tactics.” Although obscure today, the total casualties in relation to the many attacks and counter attacks at Isonzo were once legendary. The Italian high command had the supposed advantage of knowing how quickly the Western Front had stalemated due to the combination of old tactics and the defensive capabilities of new weapons against direct assaults, but they leaders did not learn the lessons and, like their counterparts in northern Europe, clung the Napoleonic strategies. John R. Schindler, author of Isonzo: The Forgotten Sacrifice of the Great War, noted of the river, now in Slovenia,

The Isonzo’s tragic recent past has been all but totally forgotten. Earlier in the twentieth century, the name evoked horror and sorrow. Throughout Europe and North America, the name Isonzo stood alongside Verdun and the Somme in the collective memory of needless sacrifice of the First World War. The terrible bloodletting that scarred France and Flanders and shattered the lives of millions did not spare the Isonzo. From May 1915 to October 1817, the Italian Army attempted to break the Austro-Hungarian defensive line on the Isonzo and to advance deep into the Central European heartland..The cost was unprecedented. Twenty-nine months of fighting on the Isonzo cost Italy 1, 100,000 soldiers dead and wounded. The Austrians, desperately holding on to every inch of ground, lost 650,000. The Italians finally crossed the Isonzo in triumph only in November 1918, at the Great War’s end, following Austria-Hungary’s complete political collapse.

It is against this background of “bloodletting” that the paintings of hospital trains by Gino Severini (1883-1966) need to be understood. Unlike the other Futurist artists, Severini was not healthy–he had tuberculosis–enough to serve in the military and spent the War in Paris. While he was watching the unfolding of a disaster, the Futurists in Milan were demonstrating in public, demanding “intervention.” After a particularly spectacular event at the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, during which they shouted “Viva la Francia”and “Viva la Guerra” and were subsequently arrested and sent to the San Vittore prison for a few days to cool off. In writing of this period in Marinetti’s life, Ernest Ialongo, stated that the poet and Futurist leader published “In This Futurist Year” “to court Italy’s university students, who had shown themselves receptive to Futurism and its nationalist message. He wrote that ‘our nationalism, which is ultra-violent, anticlerical, antisocialist and anti-traditionalist, is rooted in the inexhaustible vigor of Italian bold and is at war with the cult of ancestors which, far from welding the race together makes it anemic and causes it to rot away.'” Acting as the leader of the Futurist movement, Marinetti wrote to Severini in Paris on November 20th. By this time, late fall, the Western Front had already stalled and there had already been historic and devastating losses on the French side, and Marinetti was urging Severini, a witness to the actual costs of war, to, as Ialongo put it, “..even if it shaded into propaganda.” In his book, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti: The Artist and His Politics, the author also quoted a passage from this letter:

This war will eventually take in the entire world..the world will be at war (even if there are breaks, armistice, treaties, diplomatic congress) that is, in an aggressive dynamic Futurist state for at least 10 years. Thus is imperative that Futurism no only collaborate directly in the splendor of this conflagration (and many of us have decided to commit our bodies energetically to it) but also become the plastic expression of this Futurist hour. I’m talking about a vast expression, not limited to a small circle of experts, but a truly strong and synthetic expression that affects the imagination and eyes of all or nearly all intelligent people.” Marinetti hoped Ialongo noted, “..we will have a new, bellicose, plastic dynamism..” and predicted that in the time of war, “significant artistic originality is possible.” The letter continued, with him suggesting that the painter should be interested “in the war and its repercussions in Paris pictorially. Try to live the war pictorially, studying it in all its marvelous mechanical forms (military trans, fortifications, the wounded, ambulances, hospitals, funeral processions). You have the fortune of being in Paris right now. Take absolute advantage, abandon yourself to the enormous military, anti-teutonic emotions that agitate France.”

In defense of this sheer cluelessness of this passage, it is unclear the extent to which Marinetti, the Futurists, even Severini could truly understand the actual destructive nature of this very modern war. That Marinetti would include funeral processions in his list of “mechanical forms” is so cold that one can only imagine that, at this point in time, he was uttering meaningless slogans unmoored from actual experience. While it would be anachronistic to call out the Futurist leader for not understanding the nature of the War at hand, it is perfectly legitimate to point out that Severini addressed the La grande guerra from a sanitized distance. In addition the artist was also attentive to his own career during the War. According to the Stieglitz and His Artists. Matisse to O’Keeffe, in 1915 he sent fourteen works to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, where, along with the other Futurist artists, they were shown in a separate gallery and ignored by most critics. In the summer of 1916, Severini negotiated with Walter Pach and Marius de Zayas to arrange an exhibition at the New York gallery of Alfred Stieglitz, 291, an art dealer who disliked Futurism. The exhibition, which would be the last Stieglitz offered to a European artist, opened in March 1917, during which Stieglitz became somewhat mollified towards the style. Due to the War, Severini had to leave the art in New York and did not inquire about his paintings until 1921. It is not clear if they were ever returned and it is possible that they eventually were donated to the Metropolitan Museum of Art as a bequest from Stieglitz and the artist, who was still alive, was delighted to be included in the Museum’s collection. Among the donations were a rare diamond shaped work, entitled Dancer=Propellor=Sea (1915) that is a combination of a spinning dancer, a swirling sea and a rotating propellor.

Gino Severini. Dancer=Propellor=Sea (1915)

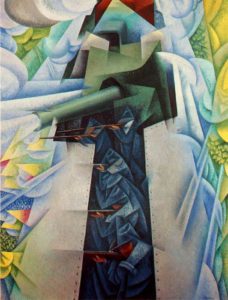

The more interesting work is a charcoal drawing, Flying over Reims (1915), probably a response to the German bombing of the Medieval cathedral in an action that would be termed a war crime today. The artist himself mentioned his limitations in saying, “I could not express my ideas of ‘war’ by painting battlefields littered with slaughtered bodies, streams of blood, and other such atrocities. My modern idea-image of war came from the concentration of a few objects or forms taken from reality and compressed into ‘essences’ into ‘pure notion.'” As shall be discussed presently, in order to create the idea-image, or a composite, Severini would have to move away from Futurism and move towards a Salon Cubism. The Reims drawing was a rare Futurist work during the War, showing movement and dramatic lines of force, foreshadowing the post-war Futurist fascination for all things aviation.

Gino Severini. Flying over Reims (1915)

Severini’s references to “slaughtered bodies” and “streams of blood” suggest that he did understand what the actual fighting was like, and it is known that he read the Parisian newspapers and used their imagery for his paintings. For example, the painting, Armored Train in Action (1915), was from an aerial photograph that appeared in a newspaper. In Inventing Futurism: The Art and Politics of Artificial Optimism, Christine Poggi explained that the image was

..a Belgium armored train, published in the bimonthly Album de la Guerre on 1 October 1915. In transforming the photographic source, Severini centered and righted the overhead view of the train, giving it a distinctly phallic shape. He also eliminated two soldiers observing the action, so that in the painting all five depicted men point rifles toward an unseen enemy at the left..If in the photograph the varied posters and individual features of the soldiers were visible, in the painting the logic of standardization takes over..the glowing red forms of the entire car at the top of the canvas intensify the erotic charge of the armored train, investing this instrument of death with simulacra life.

Gino Severini. Armored Train in Action (1915)

The next post on Futurism during the War will further examine the Futurists reaction to an actual War.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.