French Artists at War

Fernand Léger: A Case Study

Equipped only with an inadequate and dysfunctional language inherited from a mouldering nineteenth century, artists were forced to contend with a War like no other. The assumption might be that only the young, only those from the Front, only those who experienced the dangers first hand had the authority to speak. It would seem self-evident that those who possessed the keys to the new codes of avant-garde languages were able to show the truth of the Great War to those who could not serve but who wanted to understand. One of the oddities of the First World War is the trope of separation, the separateness of the civilians from the sites of fighting. With then exception of those caught up in battle zones, such as the civilians in Belgium who had the misfortune to cross paths with the German invaders, this war quickly settled into a specific strip where rows of trenches striped the continent like a gash from the North Sea to neutral Switzerland. It was here in this ribbon of modernity that the soldiers were faced with the technology of progress, express through killing machines. Beyond the band where the twentieth century was roaring into terrible life, existence in nineteenth century terms continued in security and safety. Less than one hundred forty miles away from Paris, hell had moved into Verdun, and the soldier on leave could return to a city where life went on, seemingly untouched and unmarred by the War. Although the French civilians were fully engaged in the struggle to defeat the Germans, they were not necessarily immersed in modern life.

Poilus en permission, Paris 1916

“Encounter with modernity,” a phrase written by Paul Blum to describe the experience of the soldiers who fought in the Great War. His essay, “Forces Unbound, Art Bodies and Machines After 1914,” in the book, Nothing but the Clouds Unchanged: Artists in World War I, grappled with the sudden vault into the modern age of mechanization and machines, of dehumanization and rational organization that supersedes sentiment. Blum quoted Hugo Ball, the Dada poet and performer, who presented a talk on Kandinsky at the Galerie Dada in 1917. Ball was attempting to explain the profound change thrust upon a Europe completely unprepared for the future:

God is dead. A world disintegrated. I am dynamite. World history splits into two parts. There is an epoch before me and an epoch after me. Religion, science, morality—phenomena that originated in the states of dread known to primitive peoples. An epoch disintegrates. A thousand-year-old culture disintegrates. There are no columns and supports, no foundations any more—they have all been blown up. Churches have become castles in the clouds. Convictions have become prejudices. There are no more perspectives in the moral world. Above is below, below is above. The transvaluation of values came to pass. Christianity was struck down. The principles of logic, of centrality, unity and reason were unmasked as postulates of a power-craving theology. The meaning of the world disappeared. The purpose of the world—its reference to a supreme being who keeps the world together—disappeared. Chaos erupted. Tumult erupted. The world showed itself to be a blind juxtapositioning and opposing of uncontrolled forces.

According to Ball, “The artists of these times have turned inward. Their life is a struggle against madness. “ And the poet was certainly correct, for many artists turned away or retreated or escaped during the war, especially in France. After the War, the appetite for images of a war everyone wanted to move beyond wasn’t large, to say the least. The art done during the conflict, therefore, fulfilled very specific purposes and was confined to a four year island. Many of the English artists, who were so eloquent when describing the destruction of the war on land and human faded from prominence, and the French artists adjusted their art towards the emerging post-Cubist collector base. The power of what Jean Cocteau called Le rappel a l’ order (1926) or Call to Order brought art back to a severe classicism that would reorganize the disorderly experimentations of the pre-war avant-garde. In reviewing the art of this period exhibited “Chaos and Classicism: Art in France Italy and Germany, 1918-1936,” art critic Ed Voves wrote,

This “call to order” actually had its roots in French wartime propaganda. The virtues of France’s Latin-based civilization were ranged against the Teutonic brutalism of the Germans. Before the war, néoclassicisme had languished like a discarded stage prop. In 1918, with the “Huns” surging for a second time toward the gates of Paris, Cocteau and others summoned the cultural icons of Greece and Rome to join the Allied ranks. That year, Cocteau published a book, Le Coq et l’Arlequin, which he revised and renamed in 1924 as Le Rappel a l’ordre. The message was the same, without the “us versus them” jingoism of the war: civilization must look to its ancient past to regain its bearings and enhance its vitality.

In the 1920s, Cubism had been run through the sieve of the Parisian marketplace until it had been flattened into a tamed decorative and harmless aesthetic, as in “look” or “appearance.” Order had been restored. The transformation of the art of Fernand Léger (1881-1955) is an interesting case in point. One could argue that Léger did not practice Cubism long enough or well enough to find his own voice. True, before the War, he found a distinctive style, but it was only after the war that he had something to say; and his message became one of modernity as uttered through the language of classicism. His wartime experiences seem to have been informative and transformative, maturing his art. Léger is famous for having said, “To all the blockheads wondering whether I am or will still be a cubist when I return, you can tell them more than ever. There is nothing more cubist than a war like this one, which can more or less cleanly section a man into several pieces and blast him to the four cardinal corners.”

Fernand Léger at the Front, Verdun

As a sapper or miner it was the job of the artist to tunnel under no-man’s land between the lines and to blast the Germans in their trenches “to the four cardinal corners.” After he was exposed to mustard gas at Verdun, Léger tried his hand at camouflage, hiding the objects of war, shielding trenches when possible, smothering all that could be seen with trompe l’oeil nature. As a camoufleur it was his job to make sure that everything matched the endless sea of mud, the expanse of dun colors. Consequently, one of his less well known statements touched on the experience that soldiers had in a landscape that was difficult to “read:” they developed an acute sensitivity to sound and acquired a large aural vocabulary of reverberations. As a sapper, he would have learned to listen to the sounds of the enemy digging underground in the opposite direction, so it would be natural for Léger to make this statement:

The war was grey and camouflaged. All light, colour and even tone were banned on pain of death. A blind existence in which anything the eye could register and perceive had to hide or disappear. Nobody saw the war hidden, concealed, crouched on all fours, earth coloured; the useless eye could not see anything. Everyone ‘heard’ the war. It was an enormous symphony that no musician or composer has yet been able to equal: Four years without colour.

One can imagine what it meant to the artist to emerge from below ground and into the light of day, to push aside the camouflage netting to greet the rising sun. Under such circumstances, the eye, always straining to see and to read the landscape, would be intently aware of objects. In a more familiar statement, reflecting this new curiosity to the world of light, the artist recalled his reactions to being removed from his studio habitat and his artist colleagues and being thrown into a war and new experiences.

It was during these four years which threw me suddenly into a blinding reality that was entirely new to me..Suddenly I found myself on an equal footing with the whole French people. Posted to the sappers, my new comrade were miners, laborers, artisans who worked in wood or metal. I discovered the people of France. At the same time I was suddenly stunned by the sight of the open breech of a .75 canon on full sunlight, confronted with the play of light on metal. In needed nothing more than this for me to forget the abstract art of 1912-1913.

The gun of which Léger spoke was an artillery piece, described as Matériel de 75mm Mle 1897. As Ralph Lovett, an authority on historical artillery described it, the gun had a hydro-pneumatic recoil mechanism, which absorbed the force of the firing of the shells, so successfully that, once they had developed this light-weight gun, the French “wanted no other artillery.” But there is a range limit to this gun that became apparent in 1915 in the face of German superior weapons. It can be assumed that the gun Léger admired had been modified. As Lovett explained, “By 1915, the French Army had begun to put together a balanced combination of the 75mm gun with the 155mm howitzer.” The French Soixante-Quinze is consider by some to be the first modern artillery piece because it used smokeless power and the new invention so admired by Léger, the rating screw breech, designed by Société Nordenfelt. The breech would be opened with a crank, the projectile could be trust inside, down the sleek tube and then the handle would be rotated again, closing the breech for firing.

When America entered the War, weapons had to be purchased from the French, who, by that time, had a well-stocked arsenal, and a brief film from 1918 shows the “Doughboys” or the gunners firing this large gun, mounted on two wheels, demonstrating only a slight jump back. The AEF bought some two thousand of these efficient machines. The famed .75 could fire as fast as the crew could load it with the time-fused shrapnel shells up to thirty rounds per minute or every thirty seconds, the gun could fire a shell. By 1918, these guns had become the primary conveyors of shells containing gas to the German lines. Towed by a team of six horses and served by a coordinated team of soldiers, this was the gun commanded by Georges Braque. Léger, described by Romaine Sertelet as mediocre troupier, who wanted nothing more than to return to Paris, was inspired by the business end of the gun that started all things “modern” for the French military.

There are but a few images by Léger during the War years, but a progression of sorts can be suggested. The Solider with a Pipe of 1916 is perhaps the closest to his pre-war work, which tended to be monochromatic, but the color scheme is also emblematic of the colors of the Great War–grays and browns.

Fernand Léger. Solider with a Pipe (1916)

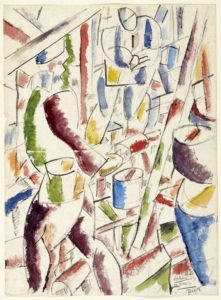

But more characteristic of his future course would be his watercolor of a sapper in Verdun, which is a patchwork of bright colors on white ground. There are glints of blue, indicating the optimistic and ill chosen French uniforms of sky blue, but the forms are more naturalistic and anatomical that the dis-articulated pipe smoker with his tube like limbs. The artist had little opportunity to do full scale paintings, such as The Card Party (1917), discussed in an earlier post, but, at Verdun, when he had time, he did a number of drawings.

Fernand Léger. Verdun. The Trench Diggers (1916)

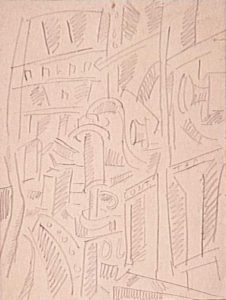

Although these drawings are minor works, but they also show the thought process of the artist as he inhales the new machines and the new mechanisms around him. Although he is part of a crew doing ancient work–digging–when Léger was above ground, he was able to take stock of this new kind of war, and, after the War, the artist shifted into what was later termed “The Machine Aesthetic.”

![2 T UMAX Mirage II V1.4 [2]](https://arthistoryunstuffed.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/060lege.jpg)

The image of a crashed airplane is jaunty and colorful, an odd reaction to what was probably a fatal crash for an aviator. Men, who, like Léger, served in the infantry on the ground envied the “Knights of the Air.”

Among the drawings Léger produced while in the service are rather conventional sketches of military life among the soldiers, ordinary soldiers, the poulis, in the trenches in moments of leisure. Léger does not appear to have been an officer as was Georges Braque and he relished mixing and mingling with the motley crew that was the ordinary French man. But other drawings sideline the human interest and foreground the mechanical with increasing abstraction. A French blog examining the question of how the Grande Guerre changed or impacted art, the author wrote, Le fait de se battre, l’action individuelle est réduite au minimum. Tu pousses la gâchette d’un fusil et tu tires sans voir. Tu agis à peine. En somme on arrive à cici: des être humains agissant dans l’inconscient et faisant agir des machines. Dans res représentations des poilus, Léger donne à la guerre son caractère abstrait par l’elimination de l’humain. Cette guerre-là, chest linéaire et sec comme un problème degéométrie. » Ainsi pour Léger, “il n’y a pas plus cubiste qu’une guerre come celle-là qui te divise plus ou coins proprement un bonhomme en plusieurs morceaux et qui l’envoie aux quatre points cardinal.

The drawings demonstrated an increasing interest in how things work, as in machines. But Léger was also drawn to the hospital where men–in pieces– were taken in on stretchers to be put together again after they been blown en plusieurs morceaux et qui l’envoie aux quatre points cardinal.

The drawings demonstrated an increasing interest in how things work, as in machines. But Léger was also drawn to the hospital where men–in pieces– were taken in on stretchers to be put together again after they been blown en plusieurs morceaux et qui l’envoie aux quatre points cardinal.

Fernand Léger. Study for Mechanical Elements (1918)

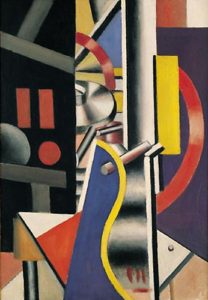

As early as 1918, Léger refined his experiences of a modern war into the next phase of modern art in which art design, and engineering have been combined. The idea of machines, which, for the artist become abstract design elements–in other words, is not necessary to define the machine in terms of what it does or how it functions, it is necessary only to show its home, the factory, where the machines live. The machine has “elements,” but it not necessary to understand what they are. When one goes back the the artillery gun, the “Seventy-Five,” it was the detail of the breech and its handle mechanism that fascinated him–not what the gun did, not how the latch opened and closes, but the abstracted mechanism itself, isolated from its purpose and examined on its own.

Fernand Léger. In the Factory (1918)

Using bright colors and simple clean forms, Léger becomes almost child-like in rendering what is a very sophisticated understanding of “machines,” in that each one does one mechanical action that is often isolated and while it is, at the same time, part of the an assemblage of machines. Together these machines in combination produce and make a final product that has no relation in form or shape or function to the machines that made it. The actual topic, whether it is of Disks (on the right) or something else, such as the rotating Propellers (on the left), human or inhuman, is reduced and reinterpreted as cogs and gears and wheels, whirring and purring in colors.

As can be seen in paintings of the period, such as The Typographer of 1918 above, there is a sense that no matter how human, the body is a machine in its own right. Elements go in to the factory and an object emerges in a kind of modern miracle that is explainable. But Léger, during this transitional post-War interlude, insists upon abstraction to indicate the gulfs between concept or design and process and execution, until finally a modern thing that we never see is produced. Later, when he reaches his “classical” phase, Léger will reintroduce the human being in his art but these works of 1918 and 1919 start the movement towards an aesthetic inspired by the machine. Here, all that is natural and/or anthropomorphic is banished: this is the brave new world.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.