French Visual Culture and The Great War

Painting War

One of the oddities of the French response of the French to the Great War was that the visual reaction was in large part one of a barrage of popular culture. While the British, English, Irish, Scottish, produced a host of remarkable works of art, both modern and traditional, paintings and photographs and movies, the French disseminated posters and cards and prints to the public. Many of the prominent artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse and Georges Braque referred to the conflict elliptically, often by turning away and seeking refuge in retreat. Others, such as Marcel Duchamp and Albert Gleizes, went into exile to America and withdrew completely, rarely recognizing the War. In his book, Esprit de Corps: The Art of the Parisian Avant-Garde and the First World War 1914-1925, Kenneth Silver wrote of Cubism that, because of its “visually explosive style,” it was

..an especially appropriate language in which to describe the destructive powers of modern warfare. Cubism offered both a system for the breaking down of forms and a method of organizing pictorial decomposition. For a war that–with its trench fighting, new incendiary devices, modern artillery, and poison gas–was unprecedented in almost every way. Cubism’s lack of association with the past was the analogue of the poilu’s general sense of dissociation. As a new visual language with a radically altered perspective, Cubism was an excellent means for portraying a war that broke all the rules of traditional combat. For those who had been in the trenches, the image of a wounded cuirassier could not possibly translate or epitomize lived experience: Cubism, on the other hand, for rendering one’s comrade whether at leisure or in the midst of battle, seemed to have a ring of truth.

English artists, such as William Roberts, the Vorticist, certainly seized upon a Cubist-Futurist vocabulary to show the insanity of the war, while Fernand Léger deployed his own idiosyncratic version of Cubism to show the war. But most of Léger’s most expressive homages to the War happened during the twenties with his series on machines. At any rate, Cubism or “Kubism” was considered “German” and, in France, was controversial in France. The vast majority of art, traditional and popular, was either not based in the avant-garde or was a very tame response to modern art. In England it was the English Vorticists and the English Futurists who convinced the British public that their native adaptation of Cubism and Futurism was the modern language necessary to explain this strangely modern war. For the French, the topic of the War had to be undertaken in a language that was “French” and recognized as “French,” not Italian and not German.

William Roberts. Gunners pulling cannons at Ypres (1918)

Fernand Léger. Soldiers Playing Cards (1917)

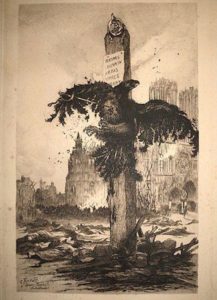

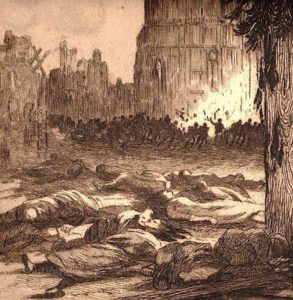

In difficult and uncertain times, there could also be something quite comforting and suitable in an account of the Great War in a tractional language that could be “read” by all viewers. For the public the international language, the lingua franca was Post-Impressionism. When the Germans bombed the great cathedral at Reims in mid September 1914, Belgium artist, Gustave Fraipont (1849-1923), used nineteenth century, almost Impressionistic, images to express the French shock at the supposed “barbarism” of the Germans. To bomb Reims was to bomb French history itself–this was the site where the kings of France since the eleventh century. But politics aside the cathedral was a magnificent work of art, and, if war were a civilized affair, Reims would have been spared and even cherished. But the Great War was a modern war and a modern war, as fought by the Germans began to rewrite the code by which armies clashed.

According to Thomas W. Gaehtgens, the Germans were stunned and aggrieved at being accused and fired back at public opinion by accusing the French of having “a base of operations” in the towers. The French countered that a Red Cross flag had been hanging off the cathedral, signifying that German troops were being cared for inside in a makeshift hospital. The exact truth may exist somewhere in the fog of war, but the paintings and prints by Fraipont fit the French mood completely. Like the Cathedral, France was attacked without cause by savages who had no regard for history or culture or even religion itself. For the Germans, nothing was sacred. The Cathedral is depicted in the balefully glowing painting (on the left) as being engulfed in shards of red as fire chews through the wooden timbers. The print (on the right) shows the building swathed in a cloud of dark smoke. Who else but beasts would attempt to destroy an ancient and beautiful Medieval monument to God? As R. Steenhard wrote,

On 20 September 1914, German shellfire burned, damaged and destroyed important parts of the magnificent Cathedral of Reims, seat of the Archdiocese of Reims, where once the Kings of France were anointed and crowned. Scaffolding around the north tower caught fire, spreading the blaze to all parts of the carpentry superstructure. The lead of the roofs melted and poured through the stone gargoyles, destroying in turn the Bishop’s Palace. The Cathedral was falling stone by stone and there was little left except the west front and the pillars. Images of the Cathedral in ruins were used during the war as propaganda images by the French against the Germans and their deliberate destruction of buildings rich in national and cultural heritage. Restoration work began in 1919, under the direction of Henri Deneux, a native of Reims and chief architect of the Monuments Historiques; the Cathedral was fully reopened in 1938, thanks in part to financial support from the Rockefellers, but work has been steadily going on since.

A comparison of Fraipont’s prints and painting with the photographs of the same event show not prosaic explosions in black and white but artistic expressions of national shock and outrage, conveyed to a French public. Indeed, with Fraipont, it was but one step away from propaganda as his later print of the “martyrdom” of Reims suggests.

A special issue of L’Art et les Artistes, which focused upon the outrage at Reims, contained accounts from America and England, all statements of shock at the crime. This international condemnation of Germany, in the second month of the War, revealed that Germany had already lost the propaganda battle with neutral nations. First, the burning of the university and library at Louvain and then the shelling of thirteenth century cathedral barely a month later. Even Italy, still hovering in a neutral position, demonstrated a public anger with the U Giornale d’ Italia commenting, Germany is entitled to the gratitude of the civilised world for many reasons, but when the excitement of war induces her children to mistake brutality for force, one recalls the infa- mous deeds of the Germans under Frundsberg at the sack of Rome, or the deeds of the bands of Wallenstein in the cruel Thirty-years war. The burning of the Cathedral is a useless act of barbarism, a lunatic outburst of wounded vanity and curbed pride. Fraipont made a print that buttressed the French case for innocence, showing the near-tragic fate of German wounded which had been rescued by the compassionate French. Images such as these played a prideful part in the propaganda war for winning the minds and hearts of the public of neutral nations, especially America, and uniting the French and the British against the Germans.

In fact the September assault was but the first that the Germans would launch: Erik Sass noted that by the end of the War the Cathedral would be hit by an estimated over 200 shells and when the Armistice was signed, only the walls were left standing. Apparently the Germans recovered from their protestations of innocence and it would be up to the American Rockefeller family to donate the money for its restoration, completed at the end of the 1930s.

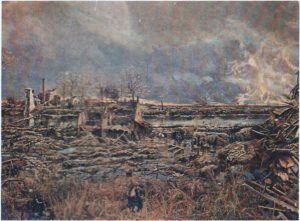

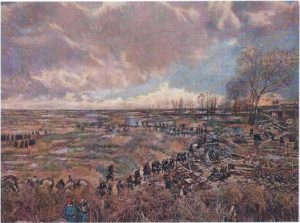

In contrast to the eventual choice on the part of the English public to accept avant-garde in paintings of the War, the French based artists who were conservative preserved the historical visual vocabulary of the nineteenth century. The way in which Fraipont depicted the blazing destruction of Reims recalls both Turner and Monet, indicating that he was formed by the Post-Impressionist generation, as was his counterpart was Alfred Theodore Joseph Bastien (1873–1955). His famous painting of a Canadian artillery unit showed the actual colors of a bombardment, with the horizon on fire. What is interesting about these Belgium artists is the extreme color, which contrasts with the dark tones favored by Matisse and the grays one often sees in English paintings. The setting of the painting, Passchendaele, which is remembered as brown mud, gray skies and black smoke from the constant bombardments, becomes a glowing scene from Hades. The intense glow is surprising to those used to black and white photography and it is important to note that these paintings would have been seen in a context of mass media news in tones of grays and blacks.

Alfred Bastien. Canadian Gunners in the Mud, Passchendaele (1917)

The forty five year old academic artist had served in Belgium’s Garde Civique until he began working as a war artist the Belgium army. William Maxwell “Max” Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook, owner of the Daily Express and early developer of mass media, collected the paintings of Bastien. A powerful man, he requested that Bastien produce works of art about the Canadian contribution to the War and apparently arranged for him to be embedded with the 22nd battalion. The British were quite familiar with his work which was often published in two page spreads in the Illustrated War News. But it was Belgium’s Prince Albert who suggested to him the work that would be his masterpiece, planned from 1914, the Panorama de l’user (1926). Completed in the mid twenties, this long extended horizontal stretch of an endless battlefield, composed of interlocking scenes.

![]()

Panorama de l’user (1926)

Measuring 115 meters in length and 14 meters in height, the massive work was eventually installed at Ostend to be of service of British pilgrims coming to Belgium to seek the final resting places of loved ones. In its final place by 1926, the panorama was arranged in the round, augmented by lighting effects, a combination of nineteenth century dioramas of old and images of modern carnage done in a Post-Impressionist style. But the Battle of Yser was among the first of what would prove to be a war that was as long as it was surreal. The Belgium defense of its sovereignty defied the German expectations of immediate capitulation and the Army fought the invaders ferociously in the beginning of the War, giving the French time to move forward to join in, the British enough days to arrive on the continent and back up the French, while the Russians mobilized in order to attack the Germans from the East. But the Belgium army continued to resist the Germans and in the flooding of the Yser by opening the canal locks at Nieuwpoort, bogged down their guns and infantry in a growing sea of expanding and deepening mud.

Speaking in London, in June 1915, the Belgium Minister, Justice Caton de Wiat, recalled how the land had once been, “Less than a year ago the region of the Yser was assuredly one of the most peaceful and one of the happiest countries under God’s sun. A country of rich pastures, intersected by ditches and canals, sown with towns and villages. Here and there, hidden in the verdure, were low, white farmhouses capped by red tiles.” He continued, “Today you must picture to yourself a bare, sinister plain, on which falls a rain of bombs and shells and shrapnel. The soil is broken by heavy traffic, plowed up by projectiles, watered with blood. Here and there the inundations have produced great sheets of water, whence emerge the ruins of farmhouses, and on which all sorts of rubbish is floating, and often corpses. And on this soil, from October 16, 1914, without respite, without interruption, men have been fighting and destroying and slaughtering one another.” It is this last stand by the Belgium people, willing to sacrifice their own land in order to fight back and make an honorable stand. The event was of special importance to the Belgium people who flooded their homeland and fought for two and a half months before they finally had to give in. The Battle of Yser was a prelude of things to come, a prediction of landscapes destroyed in the name of War.

Yser was where the Germans were stopped and for four years, the Belgians drew a line, making a front where they would continue to fight their adversaries for the next four years. The cost of the ten day battle was 76,000 Germans and 20,000 Belgians, some of whom had died of starvation. The flat plain of Yser was flooded until 1918, when the citizens of Nieuwpoort reclaimed their city in November of 1918. The large paintings, depicting a battle that changed the course of the Great War, made Bastien comfortable for life and he was able to sell volumes of infolding prints replicating the panorama for those who could not visit Ostend. The separate paintings, which were rendered in a very large scale and could be, therefore, full of details that would absorb the viewers who would scrutinize the segments of the panorama for information.

Perhaps the most famous of these artists was Georges Paul Leroux (1877-1957), who, like his Belgian counterparts was born in the nineteenth century and grew up with Impressionism and inherited Post-Impressionism and simply stopped there. This was the style, Post-Impressionism in that it was so belated, that was the leading style of the day. For most of the public, including those interested in art, it was artists like Leroux who exhibited in the Salon des Artistes Français, that were considered the prominent and famous. Leroux could not have been more acclaimed, winning the Grand Prix de Rome in 1906 and spent the vaunted year painting at the Villa Medici. For the general public, avant-garde was a fringe phenomenon of little import and therefore it was these academic artists who were entitled to speak and speak frankly to the French public.

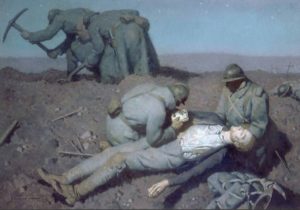

At the advanced age of thirty-seven, Leroux signed up to serve his country and was awarded two citations and the Croix de guerre. Calling up his classical learning and calling forth his academic training, Leroux produced an elegy of mourning in the pièta, Soldiers Burying Their Comrades in the Moonlight, April 1915 (1915). The painting is both real–the tragic job undertaken during rare moments of truce–burying the dead and mystical–the shining white face and shirt, dappled with bloodstains–the pale glow of the “beautiful death.” There is much in this painting that recalls Giotto, especially in the way in which the solider cradles the Christ-like soldier gently by his shoulders and the curved back of the soldier attempting to discern the identity of the dead. In the background silhouetted against the pale blue dawn sky, the crouching gravediggers, bow to the earth, like the Gleaners, and an air of sanctity blesses the sad passage out of pain and fear.

The most impactful work by Leroux is probably L’enfer (Hell) (1921), a simple title that sums up existence on the Western Front as witnessed and remembered. L’ender is not blue but red; the scene is not stilled but churned. As he recounted later, “I saw a group of French soldiers seeking refuge in one of the thousands of craters filled with water, mud and corpses.” Leroux, who was determined to represent the War in all of its horror, inscribed the scene upon his brain so that he could paint it later. At first glance the painting is hard to read, for it does not seem real at all but something out of a nightmare. The nightmare is depicted by a soldier, Leroux, who served in Verdun, and painted by a painter for soldiers in their memory and in their honor. The artist called forth the experiences that woke him up at night. At the heart of the frightening coil of brown smoke is a deep shell hole full of water. It is here where soldiers fight for their lives, struggling against mud and panic in the midst of shellfire.

Georges Paul Leroux. L’enfer (1921) The painting is also dated 1917 to 1918, but the Museum which owns it sets the “production date” as 1921.

This painting is in the Imperial War Museum which concludes its description of the painting by stating, “The artist reminds us that the earth, which in peacetime sustains health and life, has been transformed in time of war into an uninhabitable ‘Hell’ and as such L’Enfer may be construed as a most powerful anti- war image.” After the War, Leroux returned to his successful career as an academic artist and received the honors that would come to an artist of his statue. He became a member of the jury of the Society of French Artists in 1924, a great compliment to his work. In 1926, he was promoted to Knight of the Legion of Honor and photographs of the artist show him proudly wearing the medals bestowed by his nation. Another high honor was his appointment as a member of the Institut de France in 1932 and in 1945, after he lived through yet another war, he was elected its president. When he died in 1957, the art world had long since passed him by, forgetting academic and artists of the early twentieth century, but Georges Leroux left behind a horrific image of war that became the most famous of his entire career.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.