JOSEPH NICÉPHORE NIÉPCE (1765-1833)

The First Photograph and Its Rediscovery

Part Two

The Niépce Brothers, Joseph and Claude, were remarkable inventors. Or to put it another way, in the Napoléonic Era, there was little interest in industrial invention or development. Only because Napoléon thought that their motorized boat, the Pyréolophore might have some military value did their work get any traction at all. At this time, early in the nineteenth century, patronage was still royal and developers were dependent upon those in power for support. While Claude pursued the future of the Pyréolophore in England, courting the English King, George III, who actually granted him a patent, bother Joseph stayed at the family estate, a country estate of sorts in Burgundy, inventing photography. After years of work, as described in the previous post, by 1822 Niépce succeeded in capturing images on pieces of paper and on pewter plates. But in post-Napoléonic France, there was little appetite for anything that smacked of industrial development and it was clear that England, then in the midst of an Industrial Revolution, would be a better site to explore the future of photography.

The First Photograph and the Inscription on the Back

First, Niépce, apparently following in his brother’s footsteps, when to England and went to Kew where Claude was living. Once the patent on the motorized boat expired in France, Claude had sold the patent for the Pyréolophore to George III, who was quite mad at the time, which might explain why nothing came of the motor boat. But, thanks to Claude, who knew something about the activities at Kew, Joseph took the image to show to Franz (Francis) Andreas Bauer (1758-1840), who was an Austrian artist employed by the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew to dissect and draw newly discovered plants from all over the world. Because of the extensive empire of Great Britain, the English imperialists were bringing new specimens home for study and Bauer may have used a camera lucida in concert with a microscope to magnify plant parts in order to provide detailed drawings. Because the drawings were tedious and time consuming to produce, as can be seen in his 1818 book, Strelitzia depicta: or coloured figures of the known species of the genus Strelitzia from the drawings in the Banksian Library, it is clear why Bauer would have been interested in what Niépce had done with the sun’s rays and a pewter plate.

View from the Window at Le Gras

According to a recent article by Graham Harrison, The History Men: Helmut Gernsheim and Nicéphore Niépce (2013), Niépce presented Bauer with a portfolio of his work, including, according to Harrison,

..his pioneering experiments in photography including a paper contact print and four heliographic plates. Three of the heliographs were contact images reproduced from etchings, the fourth was his View from the Window at Le Gras, the world’s first photograph. Niépce showed these artifacts to the Austrian-born illustratorFrancis Bauer who was botanic illustrator to the King and a Fellow of the Royal Society. Bauer suggested that Niépce should write a memoir so that he could present the invention to the Society and perhaps gain its patronage. As instructed, Niépce hand-wrote a short description which he titled Notice sur L’Heliographie but the scientific academy declined its support, apparently because Niépce would not divulge the details of his invention.

(The phrase “would not divulge” is from an earlier account of the fate of these images written by the Gernsheims.) It is at this point that the images left the hands of Niépce and passed into the hands of an Austrian illustrator of dissented plants, but a man with important links to the British scientific community. It is perhaps a measure of how completely forgotten the experiments of Wedgwood and Davy were that the Royal Society was disinterested in the work of Niépce and the portfolio remained, also forgotten, in the Bauer family. Years later the first photograph was rediscovered by Helmut Erich Robert Gernsheim (1913-1995) (full disclosure I was his graduate assistant at University of California, Santa Barbara when Dr. Gernsheim was on the faculty near the end of his long career), who, along with his wife Alison, is considered one of if not the founder of the field of Photo History. Although the half-Jewish German refugee, in exile in England, was already an important author of New Photo Vision and a “friendly enemy alien,” he was deported to Australia where he lived in a tent, he told me, with other distinguished refugees, such as Nikolaus Pevsner, author of Pioneers of Modern Design (1936).

Gernsheim’s Improvement on the Original Image

Gernsheim was allowed to return to England where he did what no one else was interested in doing–collecting old photographs. It was out of this collecting that he and his wife were able to write a major book on photo history, The History of Photography from the earliest use of the camera obscura in the eleventh century up to 1914 in 1956. The earlier editions appeared without Alison’s name, due to chauvinism, but later editions now have her name as the rightful co-author (a known “secret” for years).

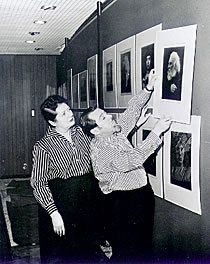

Helmut and Alison Gernsheim at Wayne State University in 1963

For years the possible existence of the Niépce photograph was suspected, and the American photographer Man Ray had even made a visit to the Niépce family home but was unsuccessful, however, the Gernsheims were determined to find the image/s. As Harrison recounted,

The View from the Window at Le Gras, the world’s first photograph, and the other artifacts that Niépce had left with Francis Bauer in England in 1827, were, after Bauer’s death, sold and later divided. In 1884 the memoir, the First Photograph and the contact print were bought by Henry Baden Pritchard, editor of the Photographic News and author of The Photographic Studios of Europe (1882). Unfortunately for Pritchard he died shortly after acquiring the items and they passed to his widow Mary. When Mary Pritchard died in 1917 the Niépce artifacts were placed in a trunk with other family belongings, deposited in a London warehouse and forgotten..Gernsheim’s search for Niépce’s lost work began in 1947, but it wasn’t until April 1950 that a glimmer of hope appeared after an appeal published in The Observer brought a response from the son of Mary Pritchard. The son told Gernsheim that he remembered the memoir and the First Photograph but he also remembered his mother’s distress at their loss. Pritchard said the artifacts had not been returned after being shown at the Royal Photographic Society’s International Exhibition which had been held at the Crystal Palace in 1898. Eighteen months passed, then out of the blue the Gernsheims received a letter from the wife of Mary Pritchard’s son stating that her husband had died and a big trunk had been opened to reveal, among the family relics, Niépce’s lost work…Mrs Pritchard wrote that although the First Photograph was among the artifacts any further effort would be a waste of time because the image had faded completely. Knowing that bitumen did not fade Gernsheim telephoned Mrs Pritchard to ask if he could see the treasure trove for himself. On February 14th 1952, at Mrs Pritchard’s home, the framed pewter plate was placed in Gernsheim’s hands for the first time. Gernsheim had not expected to see a mirror and he took the plate to the window where he held it at an angle to the light as one does with a daguerreotype. He then increased the angle further to reveal the lost image of Le Gras. Turning the frame over the historian saw what had been written there in 1827 by the botanic illustrator Francis Bauer, and read the words “Monsieur Niépce’s first successful experiment of fixing permanently the image from Nature.”

In 1952, under both their names, they wrote the account of their rediscovery of the long-lost, long forgotten “first” photograph. As the Gernsheims recounted,

There is no absolute agreement as to the year in which Niepce first succeeded in taking a permanent view from nature, though most historians favor 1824. Only the late Georges Potonniee claimed 1822, but his assumption is untenable. In spite of the fact that this photograph is called Niepce’s first successful experiment from nature, 1826 seems to us a more probable date for its production than 1824, considering the metal it was made on. For on 26th May 1826 Niepce wrote to his son: “I have sent for new pewter plates; this metal is more suitable to my object, principally for views from nature, because, reflecting the light more, the image appears much clearer. I congratulate myself, therefore, on this happy inspiration.

This brief article was printed in Image. Journal of Photography of the George Eastman House in 1952. The couple offered this remarkable find to the Royal Photographic Society, but there had been a long and contentious relationship between Helmut and British photography, which he wanted to reform. The Royal Society, according to the distinguished historian, Roy Strong, considered the Gernsheims “difficult.” The British refused the donation and the image is now preserved in the Henry Ramsome Center at UT Austin, which purchased the collection in 1963.

Henry Ramsome Center, Site of the First Photograph

Traditionally only one version of this image was published, an image of an image, filled in by Gernsheim himself to make the photograph more visible to the readers of a print publication. However, the original eight hour exposure captured on a pewter plate can be viewed only from an angle, due to its mirrored surface, and is therefore difficult to photograph and to reproduce. Today, this original image made one hundred years ago by Niépce has been successfully re-photographed and its haunted ghostly image, barely visible, gives a compelling sense of how mysterious photography must have been in the 1820s. The difficulty of viewing the image also explains why the pewter plates and paper prints aroused so little interest. What possible use could such a blurred and indistinct image possibly have? It would take another photographer to answer that question.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.