THE REMARKABLE WEDGWOOD FAMILY

Thomas Wedgwood (1771-1805)

The Invention of Photography

One of the oldest–from contemporary perspective–or one of the first accounts of Thomas Wedgwood was A Group of Englishmen (1795 to 1815) being records of the younger Wedgwoods and their Friends Embracing the History of the Discovery of Photography and a Facsimile of the First Photograph written by Eliza Meteyard in 1871. As the author of a previous book, The Life of Wedgwood on Josiah Wedgwood, Meteyard had access to family correspondence between the sons and their friends and acquaintances. She noted that the brothers of Thomas were ordinary men and that he alone had inherited his father’s gifts. Sadly he lived to be only 34 and most of his adult life he was an invalid. As Meteyard wrote,

Even as it was his intellectual and moral characteristics appear to have had an extraordinary attraction for others. He was venerated and loved in an inconceivable degree, and in the memoirs of many of his great contemporaries he is frequently referred to, and yet so slightly that we know that the lived, rather than realized an image of that man. He is thus to our generation a shadow of a shade; and yet we owe to him one of the greatest discoveries of modern times–the of Photographic Art..

According to Meteyard, Wedgwood’s invention was known to his contemporaries and there is a lost letter in which Josiah Wedgwood wrote down the details of the “sun picture” or “heliotype” at the request of James Watt(1736-1819), the famous engineer. This lost letter was written in 1799. By all accounts, inventing photography was a mere interlude in Wedgwood’s short life, something he dabbled with and then shrugged off, perhaps due to ill health. The papers containing the records of seventy five years of the Wedgwood family business had been thrown out by one of the heirs to the Etruria workshops in 1848 and were found by mere chance in a scrap-shop in Birmingham. The sheets from the ledgers were being used to wrap “butter and bacon.” The huge bulk of the records were retrieved but there were gaps that were forever lost.

But among these records is an exchange of letters between Josiah Wedgwood and a Parisian marchand-mercier Domonique Daguerre (?-1796), an important furniture designer to the king of France and English nobility, who displayed Wedgwood earthenware, including cameos, in his shop by 1787. Despite his high end clientele in Garde Meuble, the businesslike Wedgwood found Daguerre’s way of doing business to be most unbusiness-like and careless, and goods were not displayed or sold properly. However, due to some arbitration between them, Daguerre and Wedgwood continued to do business together and Daguerre even visited Etruria and could have seen young Thomas experimenting with light and heat, a current interest in the sciences of the day. A teenager, Thomas was apparently well acquainted with the early experiments with silver salts and there are letters dated from 1790 and 1791 requesting sliver from Birmingham. The letter, requesting cylinders of silver and silver wire were very precise as to dimensions and method of polishing. He also ordered barometer tubes and even drew his own design and explained how the tubes should be made, down to the placing of the flame to the bulb of glass. The young man then published the results of his experiments, two papers on the “Production of Light from Different Bodies,” in 1792.

According to Meteyard, no account exists of the images exposed, for no fixing agent was available. At the time she was writing, evidence of two of the earliest heliotypes still existed. Taken by Thomas Wedgwood at Etruria between 1791 and 1793, one is a breakfast table scene and one is a picture of a picture, an illustration from a travel book of a “Savoyard piper in the costume of his country.” Interestingly it was at this time when the elder Daguerre visited Etruria, with his son, and when the father died, somewhere between 1798 and 1802, he died in debt to the Wedgwoods. However, here is where Meteyard’s apparent lack of access to the Daguerre records becomes a problem. The Daguerre who appears so frequently in the Wedgwood accounts seems not to have been the father of the other inventor of photography, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851), whose father was Louis-Jacques. Given the coincidence of names it should be noted that there is no such thing as coincidence but the history of photography has yet to make a real connection between Thomas Wedgwood and Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre.

For all intents and purposes, Wedgwood’s health failed after 1794 and his early experiments had ceased and it is not until James Watt asked for the method of taking images with silver salts with the intent of experimenting on his own that the “sun picture” reappeared as a historical mention. By 1802 Wedgwood and Davy were both at the Royal Institution in London and their association may have led to experiments with silver salts on the part of Davy. It is known that in the Spring of 1802 Davy, in between his lectures at the Institution, began working with the heliotype process and published a paper on his findings. The paper, published in the Journals of the Royal Institution, in June was titled, “An Account of the Method of Copying Painting upon Glass and of making Profiles by the Agency of Light upon the Nitrate of Silver. Invented by Thomas Wedgwood, Esq., with observations by H. Davy.” It seemed that Davy thought of this paper as a minor notation in what was a distinguished career, for he stated that what he and Wedgwood had learned was “nothing but a method of preventing the unshaded parts of the delineation from being colored by exposure to the day, was wanting to render the process as useful as it is elegant..”

At age twenty one, Thomas Wedgwood began years of visiting physicians, including Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), poet, physician and grandfather to Charles, but his illness, whatever it was, could not be cured. By 1795, Wedgewood’s health had deteriorated to the point that he was advised by his physicians to travel. For years he wandered but during that time, he made the acquaintance of Humphry Davy (1778-1829) and the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834). Along the way he made the acquaintance, as they said in those times, of William Godwin (1756 – 1836) who was married to Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), mother to Mary Shelley the author of Frankenstein. Wedgwood seems to have funded Godwin even though he disagreed with the philosopher’s ideas. He also funded the work of Davy, after participating in experiments with laughing gas about which he wrote that he became “entranced” and that ..“Before I breathed the air I felt a good deal fatigued from a very long ride I had had the day before; but after the breathing, I lost all sense of fatigue..”

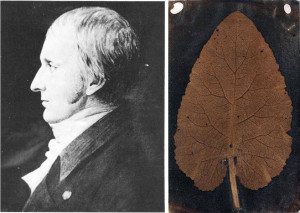

The photograph of the Leaf was put up for sale by Sotheby’s in 2008. Presumed to have been made by William Henry until photo historian Larry Schaaf attributed it to Wedgwood. If true, this image cold be the world’s oldest extant photograph. Due to the outcry of the photo historical community, the sale was cancelled until a more precise attribution could be determined.

In 1798 Davy was involved with chemical experiments in Penzance, Cornwall when Wedgwood was in the area for his health. Davy’s experiments with gas led to his becoming the head for the laboratory of the Pneumatic Institution in Bristol. The Institution was established by Thomas Beddoes, the physician to Wedgwood, and it was the famous Scottish engineer James Watt who made the equipment for the lab. The Institution became a gathering place for poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, and the Wedgwood family, all of whom enjoyed witnessing the various experiments with a variety of gases. It seems that the Wedgwoods were financial patrons of Coleridge, financing his dedication to poetry. Josiah Wedgwood and Erasmus Darwin both belonged to the Luna Society. In addition, as the result of their friendship, a Wedgwood daughter married a Darwin son and their child Charles would marry Josiah Wedgwood’s granddaughter. Thanks to the Wedgwood fortune, Charles Darwin had the leisure time to explore the science of evolution.This remarkable interconnection of family, friends, intellectuals, physicians, scientists, business men and poets is emblematic of the Industrial Revolution that would propel Great Britain to the forefront of the modern world.

Thomas Wedgwood died in 1805 and his biographer Richard Buckley Litchfield noted that friends, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and Sir James Mackintosh intended to write an essay to commemorate his life but, sadly both men were unable to complete the task. Mackintosh was apparently feckless and Coleridge was then addicted to opium or as he described it “pitable slavery.” Writing Tom Wedgwood, the First photographer: an Account of His Life, His Discovery and His Friendship with Samuel Taylor Coleridge Including the Letters of Coleridge to the Wedgwoods and an Examination of Accounts of Alleged Earlier Photographic Discoveries (1903) in 1902, Litchfield noted, as did Meteyard, that but for extant letters, the life of Thomas Wedgwood and his role in the discovery of photography would be forgotten or without evidence. As Litchfield wrote,

Of Wedgwood’s photographic work we know hardly any more that is discoverable from the “Account” in the Journal of the Royal Institution for 1802. It was evidently only an episode in his life. In his letters I find on allusion to it; nor do I find anything in his handwriting relating to his experiments in physics, save only the “Memorandum” of 1792 as to his giving up experimenting.

After the death of his father in 1795 made him a rich man, Thomas Wedgwood decided to use his fortune to do good in the world and he and his family provided Coleridge with an income of 150 pounds a year, a not inconsiderable sum for that time. In an age when travel was quite difficult, Wedgwood was forever on the move, drifting across England and, before the Napoléonic wars, wandered over Europe, often on walking tours, and even took a trip to the West Indies. But his traveling was ended with Napoléon threatened to invade England in 1803. However, Litchfield found an indication in a letter of 1800 indicating that Wedgwood may have taken up experimenting with microscopes and painted glass, suggesting photographic intentions. Interestingly enough, making a distinction between the report itself on the work of Wedgwood and Davy and who actually wrote the report itself, Litchfield reported that the famous “Account” of 1802 was unsigned but is believed to have been written by Davy because a copy was found in his papers when he died. The entire text was not reprinted in its entirety until 1902. The “Account” read in part,

White paper, or white leather, moistened with solution of nitrate of silver, undergoes no change when kept n a dark place; but on being exposed to the daylight, it speedily changes color, and after passing through different shades of grey and brown, becomes at length nearly black.. When the shadow of any figure is thrown upon the prepared surface, the part concealed by it remains white, and the other parts speedily become dark. For copying paintings on glass, the solution should be applied on leaner; and in this case it is more readily acted upon than when paper is used..The copy of a painting, or the profile, immediately after being taken, must be kept in some obscure place. It may indeed be examined in the shade, but in this case, exposure should be only for a few minutes; by the light of candles and lamps..And it will be useful for making delineations of all such objects as are possessed of a texture partly opaque and partly transparent. The wood fibers of leaves, and the wings of insects may be pretty accurately represented by means of it..The images formed by means of a camera obscura have been found too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver. To copy these images was the first object of Mr. Wedwood in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used nitrate of silver, which was mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensible to the influence of light; but all his numerous experiments as to their primary end proved unsuccessful..Nothing but a method of preventing the unshaded parts of the delineation from being colored by exposure to the day is wanting, to render the process as useful as it is elegant.

Unlike Meteyard, Litchfield does not place Davy and Wedgwood together in 1802 but the two had obviously had had long conversations about Wedgwood’s boyhood experiments. Apparently Davy, like Wedgwood before him, could not see the implications of the process and he seems to have been most interested in how copies of paintings on glass (placing glass over a print or reproduction of a painting and copying it) could be made by this method. Wedgwood was not in England when the “Account” was published and it is probable that he was also absent during Davy’s experiments. Furthermore the “Account” was not widely circulated and was available only to private subscribers such as science enthusiasts. What we now know to be an announcement of sorts of the invention of photography or a milestone along the way, passed without a ripple. The last years of his life were marked by deep depression and despair over his deteriorating health and towards the end he was taking opium for the pain. Finally in July of 1805 he went to sleep and after lingering for a number of hours with his family in attendance, Thomas Wedgwood died peacefully.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.