French Artists at the World’s Fair

The Last of Cubism, Part Three

For Robert and Sonia Delaunay, the opportunity to decorate two buildings, one dedicated to airplanes and the other featuring trains, was too good to refuse. Both artists had long been painting modern life and both lived immersed in technology—Robert in his Talbot—and in cutting edge fashions–Sonia’s “simultaneous” dresses–so that doing murals on modern transportation–trains and airplanes–the pavilions for the International Exposition of Arts and Technics in Modern Life in 1937 would be extensions of the lives they were already leading. By the late 1930s, the painting of Robert Delaunay had stiffened and thickened, lacking the translucence of color they had possessed before the War. The designs for the two buildings were the final expression of Orphism, distilled into a formula, hardened into a composition of colored discs as a signature motif. The circular forms that had once referred to the halos of light surrounding the new electric lamps for the streets of Paris could be translated into the rushing wheels of a locomotive or the swirling propellers of an airplane. The earlier works of both artists, Robert’s 1914 painting Homage to Bleriot and Sonia’s 1913, La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France, an account of a journey on a train by poet Blaise Cendrars, designed by Terk-Delaunay.

The particular buildings for the Fair, Palais des Chemin de Fer and the Palais de l’Air, designed by architect Félix Aublet, which were decorated by the Delaunays became the swan song for the couple’s collaboration and, not incidentally, for Orphism and for Cubism itself. For years, Robert Delaunay had been isolated by choice, allowing Sonia to take the lead, but the chance to do murals on such a grand scale tempted him to make his presence known to the public once more. As his friend and art historian Jean Cassou explained, “In this spirit of intuitive and amorous synthesis of Orphic cubism, Delaunay always aspired to accomplish vast works which would express some great idea collective. His isolation in our age stems from the fact that he escaped the temptation of the easel painting in order to learn of possible techniques that would reconcile painting and architecture.”

The maquette for the entrance to le Palais des chemins, representing clouds of smoke and the layout of tracks, by Robert Delaunay

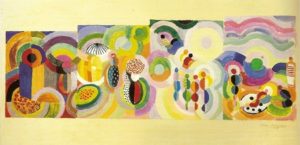

Sonia Delaunay. Voyages lointains (1937) also for the Palais des chemins

Delaunay had a long friendship with Walter Gropius and László Moholy-Nagy and had seen the Parisian debut of the latter’s famous Licht-Raum Modulator, an amazing apparatus that was a beautiful machine casting light and forming shadows. The artist was interested in collaborating with architects because he had been impatient for years with easel painting. In fact, The City of Paris of 1910-1912, shown in the Salon des Indépendants in 1912, was four meters long. Then, when he was invited by the well-known architect, Robert Mallet-Stevens, to produce a mural for the building Society of Decorative Artists for the famed Art Deco exhibition of 1925, Delaunay painted The City of Paris, the Woman and the Tower. This mural was an answer and a sequel to the earlier The City of Paris, and once more he had been called upon to do murals for an international fair. Murals in a building would give him the opportunity to increase the size of his paintings to the monumental, enveloping the viewer with discs of color.

Robert Delaunay. The City of Paris, the Woman and the Tower (1925)

This triptych was one of the last major figurative works by Robert Delaunay. By the 1930s, he had made the definitive move to total abstraction and he produced a series of paintings called Rhythms, consisting of colored discs. He translated these paintings to “wall coverings,” geometric designs featuring circular shapes applied directly onto the wall itself. The pigment substitutes, such as plaster and casein or plaster laced with sawdust or textured cement, produced raised surfaces of designs that could withstand exterior climate changes. The Reliefs were shown in a Parisian gallery in 1935 and it was at this exhibition that Delaunay met Félix Aublet, who was looking to employ unemployed artists for the upcoming world’s fair. Two years later, Delaunay had, not a wall, but the interior of an entire building to plan and decorate.

Palais de l’air with the murals visible on the back wall in 1937

Exterior of the Palais de l’air in 1937

According to the Centre Pompidou, which organized a retrospective for Delaunay in 2015 (with occasional translation assists from the author) “The Air Palace, located on the Esplanade des Invalides, with an area of approximately 6300 m2, is contrary to the Palais railway, a building designed for exhibition. All metal, it consists of two curiously heterogeneous parts: a transparent tapered lobby and a long opaque gallery, covered with cement slabs..The upper segment was 25 m by 36 m wide, the dome, which overlooks the lobby, is entirely covered with Rhodoïd, transparent material and multicolored, which are associated light projections. In the middle of colored ellipses that recall the rings of Saturn and airplane flight paths, a bridge hanging in the attic allows the public to discover, an airplane suspended in the from the ceiling, in the air, as it were. At night, the transparent walls of the hall allowed a view, from the outside, of this extraordinary cosmic composition, while the fires of three rotating lights come intensify chromatic vibration of color. Under this facility, designed by Delaunay and Aublet, two other aircraft and the latest engine models are exposed on the ground.”

Sonia Delaunay. Murals for the Palais de l’air (1937) Robert Delaunay. Hélice et Rythme (1937) For the married couple, the murals were a dazzling achievement. The success of the International Exposition of Arts and Technics in Modern Life is perhaps more in its place in history as one last bit of international cooperation than in any coherent manifestations of the themes. For many of the artists whose work appeared in the pavilions and palaces, it would be their last mature work before the Second World War, after which they would disappear from history. Artists like Fernand Léger would live another twenty years, long enough to see French art eclipsed by American art. Historians tend to prefer to discuss easel painting and often ignore the entire oeuvre of an artist. And yet the 1930s was a Golden Age for mural painting. It is rare to find an account of Paris between the Wars that goes beyond Surrealism, but many artists were drawn to the alternative of Social Realism which was diametrically opposed to the flight from reality and the journey into the unconscious taken by the Surrealists. Again, art history has shied away from political art and Surrealism, with its apparent lack of politics was more comfortable, because the politics of Surrealism–and Surrealism was political–were easier to ignore than with Social Realism. Diego Rivera left Cubism in pursuit of an art that expressed its own age and its needs in an era of social struggles and class divides. The Russian Revolution and the rise of the Soviet Union, expressed in the Pavilion, had stirred sympathies for the working classes and a desire for a more egalitarian justice. Fernand Léger. Le Transport des Forces. Palais de la Découverte (1937) Fernand Léger, trapped between the avant-garde Surrealists, who were on the wane, and the concrete abstraction of Le Corbusier, sought a New Realism that would express its own time, the modern age of the thirties, in a readable–realism–fashion without being didactic and while retaining recognizable avant-garde features. Léger said, “It’s easier to look backward, to imitate what is already done, than to create something new.” Like the Delaunays, he sought connection with modernity. The murals he did for the pavilions at the 1937 Fair showed the impact of the current debate over the role of the artist in a society increasingly dedicated to listening to the needs and demands of the working class. In France, a new government had been elected in 1936 and the forty hour work week and paid holidays became part of a worker’s right. Léger, politically inclined towards supporting the proletariat, insisted that photomontages were an avant-garde solution to Socialist Realism and its didacticism. In Realism, Rationalism, Surrealism: Art Between the Wars, Paul Wood pointed to Léger’s use of photomontage in his murals in his work for the fair as indicative of the ongoing debate of what art should be in an age of social urgency, trapped between Communism and Fascism. To anyone used to Dada photomontage, the use of mass media in a mural scale is a contradiction in terms and there is no doubt that Léger’s sincere idea was a clumsy mural, a bad solution. Like the position of the French government–in between–the struggle of French art to find the secure footing it had once enjoyed. Something had happened since the great fair of 1925 and the murals, commissioned by a government embarrassed that, in the supposed capital of the art world, their artists needed employment. And yet the argument–realism or abstraction? and if realism, what kind?–was suspended when the Second World War ended the debate, leaving important questions dangling in the margins. The late or post-Cubists works of Robert Delaunay are rarely discussed within art history and only recently has the career of Sonia Delaunay been reconsidered. Of Robert, one must read between the lines and consider the possibility that being thought of as a “deserter” because he refused to serve in the military during the Great War might have hampered his post-war career in Paris. But the lively social life of the Delaunays suggests that the career of Robert might have stalled on its own, while Sonia continued to thrive and grow as an artist. The work he did for the Fair of 1937 was among his finest and would, sadly, constitute the end of his career. In a year, Robert became ill with what was diagnosed with cancer and he struggled for three more years to survive. However, the Nazis marched into Paris and immediately the life of Sonia who was Jewish was in danger. The couple fled south to Vichy territory where they found safety. In 1941, Robert Delaunay died of cancer, leaving a wife who would outlive him some thirty years and a son, Charles, who would become a world recognized jazz expert. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.

.

.