MATTHEW BRADY AND HIS OPERATIVES

“The camera is the eye of history.” Matthew Brady

From Portraiture to the Civil War

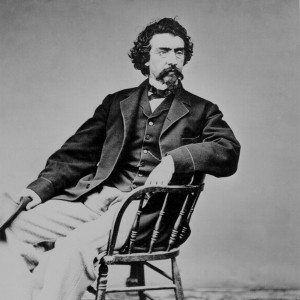

It is unclear precisely when Matthew Brady was born, in fact, in an 1891 interview, the photographer himself said “I go back to near 1823-4.” His middle name, indicated only by an initial “B,” is also unknown and may have been a single letter inserted in the middle of his plain Irish name for effect. The story he told of himself, placed Brady in an Old Testament like lineage of “begats,” creating a series of links from Daguerre to Samuel Morse to the Broadway portraitist. In fact there is no written evidence that Morse, who knew Daguerre, was ever the mentor of Brady but it is obvious, given Brady’s photograph of Morse with his chest covered with medals, peeking out from underneath his white beard, that they knew each other. Robert Wilson’s new biography of Brady, Mathew Brady: Portraits of a Nation, wrote of the lack of hard facts about the photographer. For example, there is no record of his marriage but we know that he was married. Regardless of the facts and lack thereof, it was the young man from Warren County in upstate New York who invented the photography business for the nineteenth century. Unlike his contemporaries, such as Gustave Le Gray, who decided to go into the new enterprise of making photographs for a living; Brady, who had bad vision from childhood, was never an artist but a business person who directed the production of photographs on a large scale. Brady’s simple but obvious approach to photography, which understood a photograph to be a product, crafted for maximum customer satisfaction, proved to be a recipe for success. But Brady had higher ambitions; he wanted to make history and he used photography to record the people of his own time.

Matthew Brady Seated Self-Portrait

Brady was the right man in the right place at the right time. In the 1840s, the public understood the Daguerreotype as a medium suitable for portraiture. The privilege of a likeness, the fashioning of a persona had long been the province of the wealthy and powerful, and, although there were quick and inexpensive substitutes, such as the silhouette or miniature for the middle class, there was a “readiness” for the Daguerreotype in the mind of the public that Brady could capitalize upon. Brady provided the public with a vision of–not what they needed–but what they wanted, which is the prime directive of consumerism. Brady had spent some of his teenage years as a clerk in a store and undoubtedly was aware of the importance of the display of wares for the shoppers. But he seemed to possess a sense of interior design and realized that an entrepreneur could use decor to establish a certain ambiance. Brady labeled his photographic business a “studio” a term which linked his Daguerreotypes to “art.” From 1844 to 1860, he was able to expand from one to three studios all on Broadway, until in 1860 the final studio was opened at 785 and given the (self)important name of “National Portrait Gallery.”

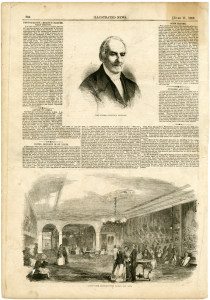

Matthew Brady’s Broadway Studio

This Portrait Gallery evoked all the trappings of the gallery or grand hall of one of those fine town homes springing up in New York. The visitor would ascend to the second floor via a wide staircase visible in the left of the engraving of the studio. The long gallery was designed to signify the ancestral manor where the family portraits lined the walls. The walk of Brady’s studio were discretely papered and the ceilings were decorated with coved moldings. Tufted benches were set up along the center aisle suggesting a site of contemplation as in museums and enhancing the importance of the personages whose portraits were arranged Salon style, floor to ceiling. An 1853 engraving titled “Brady’s New Daguerreotype Saloon” in the Illustrated News shows the long gallery divided, like a basilica, into three aisles, and grandly carpeted for the comfort of the fashionable visitors. But, unlike the stately home, this studio was a business establishment and the display room was an invitation to desire and an inducement to purchase.

Illustration of Gallery in 1853

Decades before department stores came to New York, Brady established the idea of the long display room, lined with Daguerreotypes, a place where the public, after paying a small admission fee, could stroll and browse and view the images. For the passer by, the experience of entering the elegant Broadway premises not only provided a haven and a refuge from the busy and dusty city streets but also established a clear class line, intimidating those who could not afford the three dollars for a Daguerreotype. Because Brady had perfected the art of re-photographing the unique positive, it was possible to purchase a picture of someone who was famous, but at this time, it seems that the primary purpose of Brady’s studio was to use the gallery to inspire the customer who would then want his or her face to be preserved for posterity.

Brady’s talents also extended to the fashioning of the subjects themselves. he seemed to have the ability to gain a sense of an individual’s character, if only in an understanding of his or her place in the social hierarchy of the era. Although he was perfectly capable of taking a photograph and he certainly understood the camera and its technology, Brady spent his time in front of the camera, working with the sitter. His many “operators” or “operatives” did the mundane work of “operating” the camera. The individual would arrive, suitably dressed, and it is clear that Brady understood what would photograph best in the limited technology of the time. Elizabeth Hamilton, “Mrs. Henry Wager Hallock,” the granddaughter of Alexander Hamilton and wife of a general, was posed in a dress of polka dots, trimmed in white, and so well lit, the carefully draped skirt and sleeves reveal the elaborate design and all the details of the couture work. From her erect and proud stance, it is clear that she is someone important and is aware of her connection to the American Revolution. Such collaborative self-fashioning, assisted by Brady, was something new and modern, leading to the precursor of the campaign photograph.

Portrait of Elizabeth Hamilton

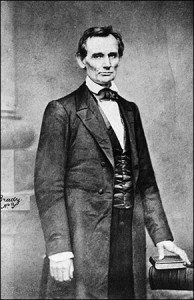

In February of 1860 Abraham Lincoln visited Brady’s studio. A far less prepossessing subject than Mrs. Hallock, Lincoln was tall and gawky, not suave and fashionable, and badly in need of improvements. Brady, conscious of the camera’s demanding ways, pulled up the collar of the Illinois politician, described kindly as “backwoods.” Fortunately, Brady’s photographs of the famous were often reproduced as engravings in periodical such as Harper’s Weekly and the artist who converted the image smoothed the disheveled hair and craggy features. Lincoln, like most of his generation, could not be at ease with the camera and was always stiff and formal, but he recognized the power of the image and credited Brady for his successful election as President. And Brady did well from his many portrayals of Lincoln, cheaply reproduced as cartes-de-visites, distributed to the public.

Matthew Brady’s February 27, 1860 Portrait of Lincoln

But Lincoln’s election also split an already bitterly divided nation and the slave states seceded from the Union and there seemed no recourse but to go to war to prevent the end of the young United States. For the new Confederate states, the “cause” was states’ rights or the right to own slaves and to traffic in human beings. For the Union, the “cause” was to preserve the integrity of the nation. Both sides assumed that the subsequent war would be over in six months. This is the phrase of many a war and none of them have ended so promptly. Matthew Brady immediately heard the call of history.

It is customary to think of Brady, the portraitist, as an American Nadar, but it is clear that he thought of himself as a historian with a camera. His project, “The Gallery of Illustrious Americans,” existed both in his New York gallery and in his short lived Washington establishment, but, to a contemporary eye, portraits are illustrations which punctuate the larger narrative of history. But that view would be an anachronistic vision. In their own time, such images of prominent people, mostly men, who ran the nation, would have been a novelty for the public. Now, thanks to Brady, they could identify the current President and even knew what Dolley Madison looked like. Now the people who consented to the rule and guidance of these individuals could connect a face to a name. For them, that connection was “history.” That said, it would be Matthew Brady who would create a modern vision of “history” as created simultaneously thorough photographs, something we now call “photojournalism.” Once again, Brady was the right man in the right place at the right time with the right vision. Given the importance of the archive he would amass, Brady’s reason for photographing what would be America’s most terrible war was mundane, even casual. He remarked, “A spirit in my feet said ‘Go’, and I went.”

And so the camera went to war once again, but this time it was different. Unlike Roger Fenton’s excursion to the Crimean War for Queen Victoria, Brady’s self-imposed task was unconnected to any government and, as a commercial enterprise, was out of the reach of official censorship. As a result, the Brady project of writing the history of a war with photographic images was literally without precedent and he and his operatives had to decide, on their own, how to proceed. “My greatest aim,” Brady said, “has been to advance the art of photography and to make it what I think I have, a great and truthful medium of history.” And so he sent his operative, nearly two dozen of them, to record the unfolding Civil War. The result were unprecedented images. No one had ever brought the war home, removed one step from the actual lived reality, as images, to be viewed close up and in the intimate surroundings of the private living room. It is hard for us, who live in such a censored world during times of war, to imagine the public, anxious for accurate news of the conflict, going to Brady’s Broadway studio to view images of death and violence and war and its costs, but the thirst for information was an irresistible impetus. Shocked at the truth conveyed through the small black and white photographs, The New York Times wrote in 1862, “Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along the streets, he has done something very like it…” Towards the end of his life, Brady remarked, “No one will ever know what they cost me; some of them almost cost me my life.”

The next posts will discuss Brady’s “operatives” in the field of war and its aftermath.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.