The First Modern Art?

A Design Revolution

“Art Nouveau” is directly translated as New Art but no where except for France was this new style ever referred to as New Art. Instead, Art Nouveau had local names or terms used in various nations and in several different localities. The many names of Art Nouveau attest to its ubiquity and to its universality of scope, not just in geographic distance but also in the number of art forms encompassed by the term/s. In his book on Art Nouveau, Jean Lahor declared that after years of scattered manifestations, the trends began to coalesce so that they could be viewed in the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris. He noted that present at the Fair and showing decorative items were Louis Comfort Tiffany from New York and Émile Gallé from Nancy, both artists who worked in glass, According to Lahor, “In 1891 the French Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts established a decorative arts division..and the Société des Artistes Français initially resistant to decorative art, was forced to allow the inclusion of a special section devoted to decorative art objects in 1895.” That was the year that, seeing a definitive trend and aware of a gathering of artists, that Siegfried Bing opened his fashionable shop, L’Art Nouveau, a name that was subsequently given to the entire movement. This elegant furniture and furnishings salon was established in the wake of the Liberty shops in London and the various enterprises of William Morris from the precursor movement, Arts and Crafts. The significant of Art Nouveau was its international scope that suggested that there was a widespread felt need to strike back against the threat of the machine, but the broad scope of the phenomenon was also problematic in that “art nouveau” meant different things to different people.

Exhibit of Tiffany products at the Universal Exposition, 1889

As Jeremy Howard wrote in his book, Art Nouveau: International and National Styles in Europe, “The vagueness of application has led to its identification with a period more than a style, approximately 1890 to 1910. This crossing of centuries is symbolic of its transcendentalism–it is both fin-de-siècle and debut-de-siècle..It can be seen as the commercialism of art, a debasement of symbolist aestheticism into the realms of mass culture and popular appeal. Or as an elitist and aristocratic, clinging to vanishing values. It is at once anti-rationalist, expressing the wildest of fantasies, and functionalist, giving material form to socialist aspirations and technological advances.” Howard criticized the “Generalized simplifications of definition have tended to arise where an overly narrow selection of media or artist devoid of comparative analysis has been exercised. The views which have gained the most credence are those with have interpreted Art Nouveau as a style, a play of surface decoration and narcissistic art for art’s sake. They have seen it devoid of socio-political message or consequence. Hence its demise when challenged by the more profound, rational and intellectual art of Modernism born in the decade before the First World War.” Most interestingly, Howard brought up the conditions of the economic opportunities of the day: “This era was the first in which the advantage and dangers of modern materialist capitalism were being consistently revealed and addressed. For Art Nouveau artists this could mean an absorption into the material world, expressed through the creation of beautiful decorative art and luxury items, with rare or exotic materials, expressing high craftsmanship, the ingenuity and uniqueness. Or, aided by new technologies, it could mean the suppression of such qualities, as well as the subjugation of the material and its decoration, in favor of new former of unified art and architecture..”

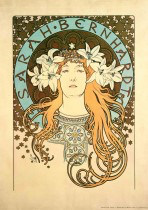

Alponse Mucha’s first poster for Sarah Bernhard, Gismonda (1895)

It can be suggested the Art Nouveau could have been both/and, which makes of the movement a Colossus with each foot in two very different camps. On one hand there is Art Nouveau, the high art style defined by name artists; but on the other hand, because of a potent combination of mass media and capitalism and consumerism, Art Nouveau became international, a universal style known and inhaled by the mass public. The Aesthetic Movement in England, the precursor and companion to Art Nouveau, insisted upon what the Germans would call a Gesamtkunstwerk or the idea that all parts of a whole had to relate to each other, aesthetically. Of course such a philosophy had always existed for the royal residences which, in the past, had established the period style of their eras, but Art Nouveau, like the Aesthetic Movement, was also a middle class movement. By middle class, I mean that the middle class, a new class of well-to-do consumers who had to be trained to make household purchases in the spirit of art and good taste. It can be said that the work of Oscar Wilde, lecturing American and British audiences on the “House Beautiful” paved the way for an appreciation of an even more sophisticated range of artistic products.

In their very interesting book, The Science and Art of Branding, Giep Franzen, Sandra E. Moriarty noted that the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk in its modern sense originated with the German composer, Richard Wagner, and they compare the “unified work of art” to “successful brands,” which, “gives expression to a certain vision, a certain body of thought or mental ideal that can sustain its focus over time..All the possible ways in which a brand manifests itself are integrated into the total harmony of an interconnected whole.” They continued, discussing Art Nouveau directly: “Essential to Art Nouveau was the idea of striving toward beauty in art and in all of life. This was about total renewal, in which everything should harmonize with everything else in its surroundings. Charles Rennie Mackintosh..expressed the ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk as a ‘synthesis or integration of myriad of details,’ the product of a ‘discriminating thoughtfulness in the selection or integration of shape, decoration, design for everything, no matter how trivial.'” In comparison to Wilde’s practical lectures on reforming design, Art Nouveau erected a position that not only reformed Victorian abundance but also presented a new style which was decorative but an artistic and inventive version of ornamentation but based upon the principle of Gesamtkunstwerk.

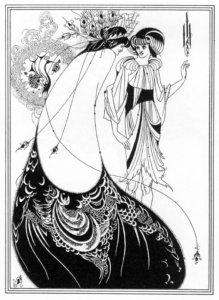

Aubrey Beardsley. The Peacock Skirt (1893)

Therefore, propelled by a philosophy based upon aesthetics and capitalism, Art Nouveau also wiped away to architectural eclecticism and historicism of the previous century. As was pointed out, each nation clad its buildings with bits and pieces of architectural details that evoked their unique past. But Art Nouveau was unique in that it was an international style, in fact, probably the first international style. Oscar Wilde’s House Beautiful was “cosmopolitan,” that is linked to London taste, but Art Nouveau erased borders and imposed a specific style upon all cultures—pan-European. The loss was of distinct cultures combined with the paradoxical manifestation of local tastes, the gain was the first “modern” style. Internationalism would become the trademark of modern design for the next one hundred years. This meta style with its meta narrative laid the foundations for the Gesamtkunstwerk that would return after the Great War in the form of “Modernism.” Art Nouveau, like modernism, had its distinctive visual language, a language that could be applied to all things, from the pages of books illustrated by Aubrey Beardsley to the cigarette case designed by Faberge for Russian royalty to the apartment building in Barcelona but by Antonio Gaudi. In other words, a middle class person could purchase a Mucha poster, while a wealthy home owner, like David B. Gamble in Pasadena could order a Tiffany design for his front door. One could argue that the “universality” of Art Nouveau was part of its Gesamtkunstwerk or its totality. Art Nouveau was also paralleled by a series of Secession movements in German speaking nations and independent salons in Paris that announced the modern rebellion of artists against nineteenth century taste and rules of presentation. However, intriguingly, in view of France’s domination in the applied arts, it was in Germany and Austria that reforms in design and reforms in the fine arts were exhibited in the same spaces. In Paris, the Salons were late in exhibiting anything outside of painting and sculpture, and, consequently, would be a decade behind the Germans in developing architectural theories that encompassed positions on modern interior design. Thanks to the turn of the century “workshops,” such as the Wiener Werkstätte and the numerous Deutsche Werkstätten, all of which helped to pave the way for modernity in the years just before the Great War, the Germans were integrating fine art and design, just at the time when the French were beginning the process of banishing Art Nouveau from avant-garde art.

Charles and Henry Green. The Gamble House front door with Tiffany Glass (1908)

Therefore, the philosophy of Art Nouveau, which envisioned the home as a Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art, had a strong German slant, combined with the English penchant for reform. Characterized by natural movement and organic shapes, Art Nouveau was curvilinear and complex, and, like Victorian taste, beset with horror vacui or fear of empty spaces. Like the Arts and Crafts and Aesthetic movements in England, continental Art Nouveau stressed artist-made home furnishings and the importance of craft over manufactured objects, and the significance of originality rather than mass manufacture. The result of the aesthetic credo of Art Nouveau was a movement which provided a new visual graphic style, accessible to the public through posters and book illustration, while the actual works of art themselves, such as elegant vases, were expensive luxury items. The Art Nouveau artists and designers were determined to offer objects of beauty and good taste to offset the stuffy and overwrought Victorian scenes of clutter that still scarred the souls of those who were artists. The totality of the vision of Art Nouveau, the strong graphic lines, the cool and restrained colors and the slow rhythms of the arabesques, was almost unprecedented in that artists and architects, painters and graphic designers, jewelry makers and fashion designers were all in sync to the extent that a book illustration by Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) or a fabric pattern by Charles Voysey (1857-1941) could coordinate in an apartment designed by Antoni Gaudi (1852-1926) and furnished by Louis Majorelle (1859-1926). Each nation had its own name for this movement, but whether it was the Liberty Style in London or Modernisme, the Catalan Art Nouveau. The Moravian artist, Alphonse Maria Mucha (1860-1939) could train in Vienna and Munich, move to Paris and make posters for the actor Sarah Berhhardt. His graphic art, like Art Nouveau design itself, was flexible and versatile, transferrable from posters to ceramics to ornamental screens to stained glass to jewelry. In his book, History and Culture in Italy, John Hendrix discussed the expansiveness of Art Nouveau in architecture, mentioning the presence of Art Nouveau buildings in Prague, the importance of Victor Horta in Brussels:

“Done well, Art Nouveau architecture is extremely expensive to produce, as it requires the most skilled masons and a lot of time to produce individual forms in iron, glass, or masonry. So the movement only lasted about ten years, but during those ten years at the turn of the century the movement left a defining mark on cities around Europe. In Vienna it as called Secessionist Architecture, practiced mostly by Otto Wagner and associated with the art movement led by Gustav Klimt. In Italy, it was called Stile Libertà, and flourished in the city of Bari, on the southern Adriatic coast. In Spain it was called Moderismo, and practiced by Antonio Gaudi in Barcelona. In Prague the best examples of Art Nouveau architecture are the Hotel Europa, the Municipal House, and the Wilson Railway Station.”

While modern design borrowed the universality of Art Nouveau and could shift from architecture to jewelry to furniture and so on, but unlike modern design, Art Nouveau was about more than simply design. Art Nouveau also had external content in that it was influenced not just by nature and natural motive but by Symbolism, a parallel movement in poetry and literature. Symbolism evoked rather than explained, implying layers of meanings in a few words or with powerful images. Using the powers of summoning subconscious reactions, Art Nouveau motifs and illustrations could conjure up ancient religions, atavistic history, intriguing mythology. Freed from realism, Art Nouveau explored the limits of illustration of famous works of literature, bringing fresh reinterpretations to old stories. The master of Art Nouveau illustration was the young artist, Aubrey Beardsley (1872-1898) who, like Mucha, became one of the artist who became iconic in Art Nouveau. His black and white drawings were the drawing equivalent of the glassworks of Émile Galle (1846-1904) of the School of Nancy—a recognizable signature style. Combining narrative with image, poetry with practical design, Art Nouveau was interdisciplinary. Modern art would never be so involved in other fields and preferred to carve out its own narrow paths. And yet Art Nouveau had its own legacies.

Ferdinand Khnopff, I Lock the Door Upon Myself, 1891

Art Nouveau had its own parallel movements and/or social conditions: the Symbolist Movement and the rising nationalism and assertive regional identities that preceded the Great War that broke out just a few years later. Symbolism, an art movement wedged in between Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, was also international, with its “stars” such as Ferdinand Khnopff (1858-1921), located far outside of Paris. But Symbolism was also a pan-movement in that it was poetry and music, a choice of colors, pale and nuanced, in the visual arts, and a poetry of Baudelariean “correspondences.” Just as Symbolism was a reaction against the perceptual approach of the Impressionists and the stolid realism the had reigned in the arts for decades, Art Nouveau and its insistence on artistic freedom and the play of the imagination was a reaction to the positivism of the machine and its abilities to make all things–except an environment made for humans by humans.