Artist and Revolution

Art at Ground Zero, Part One

In 1981, the Guggenheim Museum in New York presented a remarkable exhibition, selections from the collection of an otherwise unknown individual, George Costakis (1913-1990). Born in Russia, a nation he considered his home, Costakis was the son of Greek parents who did business in Russia. He was “Greek” and had a Greek passport, but he lived most of his life in the Soviet Union, working at the Canadian Embassy, where his job was organizing the service staff for the ambassador. According to one of his biographers, Bruce Chatwin, Costakis wanted to do “somethimg” to make his life worthy and began collecting art in Moscow around 1946, a time of hardship when a number of privately held goods came up for sale. Undoubtedly there are entire stories attached to each object he purchased–pieces from collections sold off by “white” Russians fleeing the “reds,” and later, perhaps even art looted from Germany, unmoored from provenance, but the total collection grew into something impressive and unprecedented. However, his interests changed from traditional classical art to an obscure view of “modern art” when Costakis was introduced the the brightly colored works of long forgotten artists, once part of the then forgotten “Russian Avant-Garde.”

The 1981 Guggenheim Museum Catalogue

Under Stalin, abstract art was banned and Socialist Realism ruled as the desired mode of communication. No one wanted, much less remembered, the art produced by a disgraced and discarded group of artists, many of whom were dead. The Guggenheim Museum described how Costakis was impacted by his discovery of the avant-garde: “One day he was shown a brilliantly hued abstract painting by Olga Rozanova, an artist of whom he had never heard. Its impact upon him was instantaneous: ‘I was dazzled by the flaming colors in this unknown work, so unlike anything I had seen before.'” Stunned by finding a neglected body of art by Russian artists, Costakis began to hunt for the paintings of Kandinsky and Rozanova and Popova, searching like a detective on the trail of treasure for lost works of art. In the fifties, there was no competition for these works, and Costakis, as a Greek, was able to amass an impressive collection, which lined the walls of his home, covering all available space, stacked in piles, and numbering in the thousands of objects. Over the years, his Moscow apartment on Bolshaya Bronnaya Street became a place of pilgrimage as the grip of Stalinism slackened and people began attempt to fill in the early Revolutionary years lost to unending oppression.

Olga Rozanova. Battle of the Futurist and the Ocean (1916)

In his biography of the collector, Peter Roberts, who saw the collection in 1957, recounted his experience:

In 1957 I was not alone in my ignorance of the avant-garde. Few people other than art historians, and not many of those, had any detailed knowledge of this movement. Except for those such as Chagall and Kandinsky who had gone abroad at the time of the revolution and had become famous in the West, the artists who comprised the movement were largely unknown. Most of them were dead by 1957; few of them had continued painting after 1934, when their brilliant style was peremptorily suppressed and forbidden by Stalin.

In his book, George Costakis: A Russian Life in Art, Roberts indicated that the unorthodox collecting of the Greek citizen working at the Canadian embassy using Canadian money attracted the attention of the KGB, which may or may not have understood what he was doing but were concerned at the growing numbers of foreigners who wanted to view the collection put together by a person who was considered “crazy.” However, those in the art world, curious as to the contents of his apartment, and those in the museum circles of Russia, were aware that the art was potentially very valuable–not in Russia, of course, but outside in the West. By 1978, Costakis was officially considered a “traitor” and was forced to leave the Soviet Union, his lifetime home. Because he was allowed to take only one thousand two hundred works from his collection out of the USSR, under duress, he generously gave a large portion of his collection to the State Tretyakov Gallery and departed for Greece.

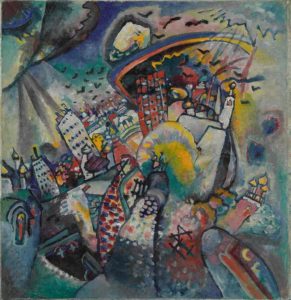

Vassily Kandinsky. Red Square (1916)

Almost immediately, his collection, or what was left of it, became available to the West, supplementing what little was known of the suppressed Russian avant-garde movement, such as the foundational work by Camilla Gray, The Russian Experiment in Art. 1863-1922, published in 1962. In a 1963 review of this seminal and pioneering book, Mary Chamot wrote in the Burlington Magazine, “Armed with a knowledge of Russian, and an immense amount of courage and determination, Camilla Gray has succeeded in contacting the few survivors of the artistic groups she writes about; she has also had access to a number of documents to be found only in Russian libraries and, perhaps most difficult of all, she has managed to see and obtain photographs of the works of art closely guarded in Russian Museum Stores.” Other reviewers were less kind, pointing to the limitations in the book, caused, for the most part by Gray’s decision to begin in 1863 and end in 1920, but the research was undoubtedly shaped by the amount of access to materials in Russia obtainable by a scholar in a period when the Cold War was at its peak. That said, the book would have provided at least a platform or a foundation upon which to build a study of Russian art, and the arrival of the Costakis collection would have literally thrown open the doors to the wide range of artists involved in the avant-garde movement before they were suppressed by Stalin. Commenting in 2011 on the slow revelation of revolutionary art and the difficulty of building a discourse on unavailable art, Owen Hatherley wrote for The Guardian,

(Costakis) created what has been called a “futurist ark”, buying up drawings, paintings and sketches by artists who were dead, discredited, forgotten, prohibited, or who had moved on to the very different “socialist realism” prescribed from the 1930s onwards. Until Costakis’s collection went public, there was only a vague idea that something extraordinary had happened in the former Russian empire – perhaps a couple of mentions of Kasimir Malevich or Alexander Rodchenko, usually in connection with the German artists they had inspired. Costakis’s work was aided from the 1970s on by the archaeological research of the Soviet historian Selim Khan-Magomedov and the late English architectural writer Catherine Cooke; it’s no exaggeration to say that without this small group of people, the current prominence of the “Russian avant garde”, which has featured in seemingly dozens of exhibitions on the heroic era of modernism over the last decade, would have been impossible.

Aristarkh Lentulov, Kislovodsk Landscape with Gates (1913)

Obviously, what happened the the Russian Avant-Garde? is a compelling question, as is the question: what happened to the artists? The traditional attempts to understand these long-lost artists have usually relied upon the connections, both stylistic and intellectual, between the West and the Russian artists. As pointed out in earlier posts, there is a distinct break in the narrative of the progression of avant-garde art in Russia, and it is the trauma and freedom of the Revolution that severs the artists from the West, forcing them to produce not “Russian” art but “Revolutionary Art.” Before the War broke out, the artists responded to art from Paris and Berlin but translated what they saw into objects that were semiotically “Russian.” During the War, the artists continued mining and developing their pre-war ideas with little interruption. But the Revolution changed everything for these artists, isolating them from any ties to Western Europe they might have had, and, indeed, the authorities were inclined to force them to stay in their homeland. Signs of governmental oppression were apparent from the start of the Revolution and it quickly became clear that if one wanted to work, one needed permission and support from Communist leaders. The artists with pre-existing European connections were the first the leave, signaling that the first phase of “the Russian Avant-Garde” had ended. The great ballet impresario, Sergei Diaghilev chose to not return to Russia after the Revolution and, strangely, the famous Ballet Russes never performed in their homeland. Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov left for Paris when the Great War began. Marc Chagall left his homeland in the early twenties and only with special permission. Kandinsky left at the same time as Chagall, taking a job at the Bauhaus. None of these artists would ever return to Russia, except for Chagall, who made a quick visit in 1973, only to find the world he left behind gone forever.

George Costakis with his collection in the 1970s

From the time of the Revolution, especially the October Revolution, the artists who stayed behind were at ground zero, a site where an old world had violently ended with such finality that the old art, once thought so darling in front of the backdrop of the anachronistic regime, now was “bourgeoisie” and out of step with the brave new world that had to arise from the ashes. For a few brief years the artists had tentative government permission or benign neglect to create new art for a new world. Although they threw themselves into the task with great and naïve enthusiasm, those in power had no definitive concept of what the role of art should be in the Communist proletariate society and no instructions to give to artists. Over time, the Soviet Union would have very specific guidelines, but in the beginning, the officials were preoccupied by the internal civil war between the Reds and the Whites. As intellectuals, the artists were always on the side of revolution, which is to say they wanted change and they relished the opportunity to be part of the vanguard of a new visual language. Unfortunately, as has been pointed out earlier, the artists themselves were internally conflicted, split off into different factions and went in multiple directions. Some wanted to continue bourgeois painting, while others wanted to experiment constructively as engineers rather than create as artists, still others wanted to contribute to the production of an art dedicated to the Revolution.

Vassily Kandinsky, a traditional Expressionist artist out of place in Russia, complained in 1920: “Even though art workers right now may be working on problems of construction (art still has virtually no precise rules), they might try to find a positive solution too easily and too ardently from the engineer. And they might accept the engineer’s answer as the solution for art—quite erroneously. This is a very real danger.” Unlike Vassily Kandinsky who was still involved with German ideas, Kazimir Malevich was more the native son referred to the Productivists and Constructivists as “lackeys of the factory and production.” He equated utilitarianism and Constructivism, which he disparaged as “subsistence art.” On the other hand, the new antagonist to Malevich, Vladimir Tatlin declared, “The influence of my art is expressed in the movement of the Constructivists, of which I am the founder.” But he rejected the Moscow group of constructivists and its leading figure, Rodchenko, and went his own way. The result of the dissension about the use of art and its role in social change was a splintered art movement that failed to present a either a united front or an ordered or an orderly slate of solutions to the government.

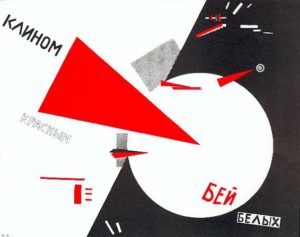

Kazimir Malevich. Portrait of M.V. MatyUshin (1913)

The government, for its part, had issues more pressing than coming up with an art program for the artists, but, on the other hand, those in charge also recognized the importance of art, its power to do harm or good, support or undermine the ideals of the revolution. At first the most obvious reform to make was the extrication of the production of art from the bourgeois class and freeing art from the mechanisms of capitalism. Art should be in the service of the people, the state and removed from the corrupting effect of being a decorative luxury item. As the Commissar of Enlightenment, Anatoly Lunacharsky, also known as the Soviet People’s Commissar of Education, issued a new definition for art very early after the Revolution: “The Proletariat must finally eradicate the sharp difference between life and art that has concerned the ruling class of the past. From now on art for art’s sake does not exist. In the hands of the Proletariat art will become a sharp weapon of communist propaganda and agitation. In the hands of the proletariat art is a tool, the means, and the product of production.” In other words, art would become art for everyone, not a consumer good for the wealthy elite, and, therefore, its role would change from passive to active, suggesting a reduced role for painting and an enlarged role for graphic design.

El Lissizky. Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge (1919)

As we move to the next posts on Russian Revolutionary Art, it is important to remember that, in the minds of the intellectuals, the Revolution itself was based in Marxist philosophy. They assumed that the Revolution was the result of the thesis-anti-thesis of capitalism and the failure of capitalism and class warfare. Having succeeded in bring about the inevitable collapse of the government, the Communists dreamed of a “dictatorship of the proletariat.” Without class hierarchies, everyone would be part of the proletariat or urban lower classes, the true revolutionary foot soldiers. The state would wither away, as Marx predicted, and the people would govern themselves. In her book, The Russian Revolution, Sheila Fitzpatrick noted that the most fervent dreamers imagined a cold, clinical and impersonal state, run by machine-like bureaucrats. The steely mind-set, devoid of personal (bourgeois) feelings and full of ideology imagined that the state would be a “well ordered machine.” In this new world, the family was secondary to the state and it was a given that, within marriage, women were oppressed. Children were recruited by the state to watch their nostalgic parents for any lingering bourgeois sentiments. The entire world was to be economically remade according the what the Revolutionaries considered to be Marxist beliefs and socially reexamined in terms of their interpretations of Engels. To be an artist in this utopian era was to be a righteous radical. As Fitzpatrick wrote,

Avant-garde artists like the poet Vladirnir Mayakovsky and the theatre director Vsevolod Meyerhold saw revolutionary art and revolutionary politics as part of the same protest against the old, bourgeois world. They were among the first members of the intelligentsia to accept the October Revolu- tion and offer their services to the new Soviet government, producing propaganda posters in Cubist and Futurist style, painting revolutionary slogans on the walls of former palaces, staging mass re- enactments of revolutionary victories in the streets, bringing acrobatics as well as politically-relevant messages into the conventional theatre, and designing non-representational monuments to revolutionary heroes of the past. If the avant-garde artists had had their way, traditional bourgeois art would have been liquidated even more quickly than the bourgeois political parties. The Bolshevik leaders, however, were not quite convinced that artistic Futurism and Bolshevism were inseparable natural allies, and took a more cautious position on the classics.

Meyerhold’s 1922 production of Sukhovo-Kobylin’s The Death of Tarelkin

It is customary to begin any discussion of the avant-garde made during the Revolution to begin with Constructivism and Productivism, with a side bar about the quarrel between Malevich and Tatlin, but it is also useful to shift the focus away from elite art and to investigate popular culture and how certain artists embedded themselves in the vernacular in order to coin new visual currency in the service of the revolution. The raw materials, the foundational alpha and omega for the new language seeking to communicate with the proletariat and the isolated peasants in the rural regions, were sophisticated and effective at the same time. The next post will discuss the ROSTA art in ROSTA windows, a fleeting attempt at agitprop.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.