The Avant-Garde Artists and The Great War

Popular Culture

While it is undoubtedly true that the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 was somewhat responsible for the next war, the Second World War, it is also true that the First World War put an end not just to some empires but, most importantly, to the idea of “empire” itself as being legitimate. The German Empire ended on the battlefields of Flanders, the Ottoman Empire was systematically carved up by the Allies, happy to share the spoils of victory with each other, and the Russian Empire, undermined by incompetent leaders and unstable monarchs, fell like a precarious soufflé. Before the Great War, artists in Russia had been political in the sense of being part of the avant-garde, biased towards modernism and against the old order of things. The Russian Empire, abetted by the Russian Orthodox Church, was notoriously opposed to change and to all things modern. But, given that Russia was a police state, seething with plots and counter-plots, it would have behooved the intelligentsia to make revolutionary art and to not make political revolutions. However, these avant-garde artists lived in a time of political revolutions and were witnesses to the collapse of an empire. As they came of age, Kasimir Malevich and Natalia Goncharov would have learned of–through the veil of censors–the Russian defeat by the Japanese in 1903, the first time a European power had lost to an Asian power. Vladimir Tatlin and Varvana Stepanova would have lived through the Revolution of 1905, which was brutally put down by the Empire in what would be its last gasp or grasp on power. The social and political forces gathering against the Romanov Dynasty were merely interrupted by the Great War, for, with hindsight, it appears that revolution was inevitable, war or no war.

The Russian participation in the Great War started with patriotism and ended in the collapse of the Dynasty and the fall of the Empire as the Communist forces, attacking internally, spread discontent within the fighting forces. Unlike the other nations, Russia was not industrialized and was not prepared to fight a modern war. Despite the fact that Russia had a larger and better equipped army than the Germans, it was not as well led and, over time, it became unclear to the Russian soldiers what they were fighting for–a Czar who was content to sacrifice their lives on the Eastern Front? In fact by 1917, mutinies among the British and French militaries were not uncommon, and the Italian commanders would routinely execute soldiers who did obey orders; but patriotism depends upon a basic faith in the leaders and in the government. There was enough faith in the English and French authorities and their governments to convince the bulk of their armies to fight to the end. This loyalty or trust was absent among the Russian troops, especially after the terrible and humiliating loss at the Battle of Tannenberg. As early as August 30, less that a month into the war, 92,000 men were lost. Then a week later, another 100,000 casualties occurred at the Battle of Masurian Lakes. The “winter war” of 1914-1915 cost yet another 190,000 soldiers. All these losses in a few months. By the end of the year, two million Russian men were lost to the War. Once the Czar personally took command of the army, the end was not far away.

When the Czar abdicated, a provisional government under Alexander Kerensky was formed and kept fighting a War that no one wanted to continue to fight, fueling the victory of the Communist revolution. Once in power the Communists negotiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, giving away large chunks of the former Empire in order to get out of the War and carry on with the Revolution. For the next four years, civil war ripped the new nation apart as the “Reds” and “Whites” fought for control over what would become the Soviet Union. The fact that the Communists ended a War began by the Romanov Dynasty meant that when the history was written by the Communists, the Great War was an “imperial” war of “empire” and not an event to be proud of. After the War, the other nations, even the defeated Germans, marked the sacrifices with memorials, but in her interesting book, The Great War in Russian Memory, Karen Petrone noted that “As the successor state to the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union was unique among the combatants in the virtual absence of public commemoration of World War I at the level of the state, community, and civic organizations, or even individual mourning. Scholars generally agree about this erase of memory..The Soviet government generally ignored the war and instead poured its energies into creating a myth of the revolution, construction Sovietness through a conscious process of forgetting imperial Russia’s last war.”

In 2014, the centenary of the beginning of the Great War, the historian Sir Max Hastings stated for The Moscow Times, “World War I was very nearly written out of Russian history during the early years of the Soviet Union because of the Bolshevik view that it was a capitalist war in which the Russian people had been the victim rather than the protagonist.” But in August of that year, Vladimir Putin spoke in a rare commemoration ceremony memorializing The Brusilov Offensive in the Spring and Summer of 1916, when the Russians successfully attacked from the Eastern Front in an attempt to draw the Germans away from Verdun and the Somme. Although Putin was probably exaggerating when he spoke of the fame of this battle, he was literally the first Russian official to mark an event in the Great War. As he said, “Today, we are restoring the links in time, making our history a single flow once more, in which World War I and its generals and soldiers have the place they deserve, and our hearts hold the sacred memory that they rightfully earned in those war years. As the saying goes, ‘better late than never.’ Justice is finally triumphing in the books and textbooks, in the media and on cinema screens, and of course, in this monument that we are unveiling here today.”

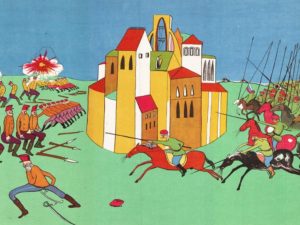

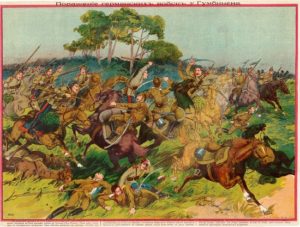

The deliberate erasure of the memory of the Great War in Russia means that it has been in just the past few years that serious study of the War began among Russian scholars. But there is an existing and compelling narrative of the War, left behind by the artists who reacted to the War for the three years Russia was fighting. It is through their work that it is possible to view the patriotism felt by Russians when their country went to War. In the fall of 2014, the Grad Gallery for Russian Art and Design in London showed a collection of rare prints, popular art and outright propaganda pieces, many being displayed for the first time in a century. Some of these prints by Russian artists, both unknown and famous, are rather amusing and delightfully folksy, such as Aristech Lentulov’s The Austrians Surrendered Lvov to the Russians like Rabbits Defeated by Lions, 1914 (left) and others are outright fantasy propaganda, such as The Russian War Against the Germans (right), while others were visionary, such as The Great European War, A Battle in the Air, 1914 (below).

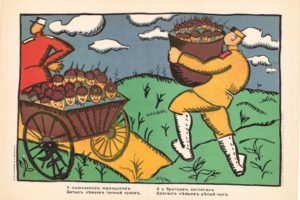

Emerging unexpectedly in the midst of his Suprematist period, the series of prints executed by Kasimir Malevich supporting the War were totally uncharacteristic of the artist’s avant-garde oeuvre. The lithographs seem to be made for children for they are comic and not serious considerations of war and its consequences. But there are reasons for this unusual collection of prints from an artist who was working abstractly by 1914. In writing of the impact of the War upon Russia and its artists, Aaron J. Cohen noted that the Russian Empire did not have a tradition of heroic military painting and that Russian audiences for academic art seem to have preferred genre scenes to visions of martial glory. In addition, he noted that the defeat of Russia by Japan, which to us now seems to be a portent of things to come, went almost unnoticed or at least unreported in the Empire. The conclusion one can reach is that Russian artists rarely dealt with the topic of war and had not considered a modern war at all. Art was not necessarily supposed to react to war or to military affairs and, in contrast to England and France, the two spheres were kept apart. This history of detachment from war might explain the divided response of Malevich, who, on one hand, did a series of lithographs, which functioned within popular culture with simple slogans or descriptions aimed at a public with limited literacy, while on the other hand, participating in avant-garde exhibitions.

Kasimir Malevich. Our French Allies Have Filled a Cart with Captured Germans, And our British Brothers have a Barrel full (1914)

In his book, Imagining the Unimaginable. World War, Modern Art, and the Politics of Public Culture in Russia, 1914-1917, Cohen wrote, “The main forum for Russia’s visual culture of war was not the art world but the mass media,especially the popular prints (lubki), posters, pamphlets, and illustrated journals that flooded the book market with wartime images during each conflict. War and art are seen to be mutually exclusive activities..War art did not exist within the official sphere.” It seems clear that Malevich was active in the area which had been traditionally available for artists and altered his art to fit the audience’s expectations, producing a group of semi-amusing lubki.

Kasimir Malevich. Look Look, Near the Vistula, The German Bellies are Swelling Up (1914)

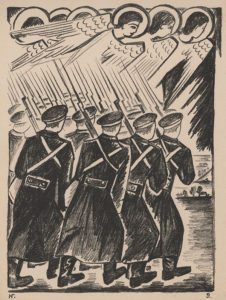

The work Natalia Goncharov (1881–1962) executed for the War followed the same pattern of doing prints in a folk style for a general non-art audience. Her series of lithographs, issued in the Fall of 1914, presented a powerful narrative of Good, as led by mystical and spiritual forces, against Evil, no doubt the Germans. This message that God was on the side of the Russian Empire was not merely a patriotic reassurance. By the fall, two major battles had been lost and the armies had been soundly defeated and decimated, so the news that heavenly help might be on the way, would have been welcomed. The saints and angels descend to earth and mix in with the humans, blessing them, protecting them, comforting them. Shortly before the War started Goncharova had produced a series of Neo-Primitivist paintings, based on Russian folk icons and was criticized by conservatives for a sacrilegious appropriation. But the reception for these prints, with her “style” being removed from the precincts of the avant-garde, was more positive.

Natalia Goncharova. The Christian Host, no. 9 from the series Mystical Images of War [Voina: misticheskie obrazy voiny] (1914)

The war series is a follow up, if you will, of the exhibition that had in fact established her reputation in Moscow, a huge showing of nearly eight hundred works. This event, Vystavka kartin Natalii Sergeevni Goncharovoi, 1900-1913, took place at the Khudozhest vennii Salon in the fall of 1913. This Moscow show was followed by a highly successful joint exhibition, organized by her artistic partner and lover, Mikhail Larionov (1881-1964) for the Galerie Paul Guillaume. In 1914, therefore, Goncharova was the most famous Russian avant-garde artist, a leader in the international art world, with a major German exhibition to be mounted by Herwarth Walden at Der Sturm in the offing. However the War intervened. According to Natalia Budanova’s article, “Russian Avant-Garde Women, Futurism and the First World War,” Walden protected the large body of work, already in Berlin, for the artist and returned it to her at the war’s end. Larinov and Goncharova were forced to return to Russia, taking circuitous route. Larionov, an excellent promoter for Goncharov’s career, was drafted and badly wounded during the first year of the War. The round faced narrow eyed artist, who had invented “Rayonism,” could never as active as he had been before the War, and the couple returned to Paris. Intending to capitalize on her 1914 success with the Coq D’Or ballet, Goncharova continued her work with Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. When the couple left Russia in 1915, their exit was a rare exception, granted perhaps due to the prestige of the artist or the military service of her badly wounded companion, or the importance of the Ballet Russe. The couple was to never return to Russia. Budanova put their departure from Russia into perspective:

Larionov and Goncharova left the country at the very moment when the Russian avant-garde was gathering momentum. The mass repatriation of many Russian artists triggered by the war, however traumatic and disadvantageous on a personal level, produced a positive side-effect on the evolution of Russian modern art. In fact, it ‘marked the heyday for the Russian avant-garde,’ because such a high concentration of vigorous, creative and ambitious personalities, counting practically as many women as men, was destined to invigorate artistic life in Russian capital cities and reinforce the avant-garde Russian cultures.

One could ask “what if?” the famous art couple had remained in Moscow and mingled with Malevich and the returning expatriates, such as Luibov Popova, had been present at the creation of a revolutionary art, and had taken advantage of their fame. Although the pair lived the last thirty years of their lives in Paris in obscurity and poverty, the fate of those who stayed in Russia was equally tragic, for this was a starred and cursed generation of artists. Those who remained in Russia were impacted by the War and it can be argued that the jolt of being part of a “great,” as in expansive war, woke up that particular generation to wider social responsibilities. In Decades of Crisis: Central and Eastern Europe Before World War II, Tibor Iván Berend quoted László Moholy-Nagy of Hungary, “

At the time of the War, I developed a feeling of social responsibility, and today I feel it to an even greater extent. My conscience spoke to me: is it fitting to be a painter in an era of social change? In the past century, art and reality were separated..as a painter I can serve the meaning of life..” Moholy-Nagy’s awakening to social responsibility would direct the rest of his life, and this artist would immigrate to Germany to work at the Bauhaus. But what of the Russian artists during the Great War? Certainly they must have reacted to the War as Moholy-Nagy did and were poised to enter into an art of the social if not immediately an art of the political. The artists made a distinction between supporting the Russia people and the Russian Czar, whom they viewed as an anachronism. The War, then, could be viewed as a prelude to readiness for the Revolution and the art they would gladly make on its behalf. The majority of histories of the Russian Avant-Garde divide the production of these artists in half, splitting their work between Pre-War and Post-War work, eliding the narrow slice that directly addressed the Great War. As was pointed out, there was almost no history of Russian artists gesturing towards any war and the normal behavior on the part of the art world was to simply carry on and make art as though nothing else was happening. For the purpose of this series, a distinction will be made, however, separating the avant-garde from the art made in Russia that directly addressed the War. This narrow task is difficult because the Russian government has suppressed this slice of time and then, in turn, hid the labors of the avant-garde artists from the 1930s on. That said, the next post will continue to discuss art in Russia during the Great War, between 1914 and 1917. If you have found this material useful, please give credit to Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.