Marc Chagall and the War

Vitebsk as an Art Center, Part One

The fable that the Jews stabbed Germany in the back during the Great War began early, put forward by those who could not comprehend that the German army had lost the Battle of the Marne in 1914. This, the first of several battles over the contested land in northern France took place in September 6th and 12th and became famous in French folklore for the timely arrival of soldiers motored to the Front by a brigade of taxicabs, to fortify the beleaguered French forces. The hard-pressed French army was fighting off the Germans who could see the Eiffel Tower through their binoculars. The fact that taxicabs from Paris could casually drive to the front lines gives a sense of how close the Germans came to taking the city. The French were saved by a combination of several events, not the least the timely intervention of the British Expeditionary Force but what the decided the battle was that the Germans made a fatal mistake. General Alexander von Kluck decided to pursue the retreating French, who he presumed were making a last stand with their tattered forces, and, in his eagerness, he exposed the flank of his army. An attentive Commander in Chief, Joseph Joffre, immediately attacked with what was left of the French forces. The sudden counter-attack caught the German high command by surprise.

It dawned on (them) at long last that the Allies had not been defeated, that they had not been routed, that they were not in disarray,” wrote Lyn MacDonald in her 1987 book on the first year of the war, 1914. “Instead, aided by reinforcements rushed to the front (although most of the ones that were engaged in the fighting came by train) Joffre and his British allies repulsed the German advance in what is now remembered as ‘The Miracle of the Marne.’ Miraculous, perhaps, because the Allies themselves seemed surprised at their success against the German juggernaut. “Victory, victory,” wrote one British officer. “When we were so far from expecting it!” It came at the cost of 263,000 Allied casualties. It’s estimated that the German losses were similar.”

The unexpected defeat was so stunning that German troops could not understand why they were retreating instead of advancing. In his book on the Marne, Holger H. Herwig, recounted the reasons for the setback were mundane: “a flawed command structure, an inadequate logistical system, antiquated communications arm, and inept field commanders.” Herwig pointed out that the official German history of the war, Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918, specifically stated, “In the hour of decision over the future of the German people, its leader on the field of battle completely broke down psychologically and physically.” Despite the facts to the contrary, rather than admit to an error of judgment made in the fog of war, the German high command in the person of Erich Ludendorff wrote in The Marne Drama that he blamed the “secret forces of Freemasonry, the machinations of world Jewry, and the baleful influence of Rudolf Steiner’s ‘occult’ theosophy…” In his book, The Marne, 1914. The Opening of World War I and the Battle that Changed the World, Herwig also discussed the work of German historian, Fritz Fischer, stating that “From the moment that German troops stumbled back from the fateful river of 9 September. Fischer argues, first the government of Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and then the Army Supreme Command conspired ‘systematically to conceal’ the enormity of the defeat from the public.” Thus the “stab-in-the-back” legend was born, rising out of the smoke of the first Battle of the Marne. In 1916, the German army slandered the Jewish soldiers who served in their ranks by conducting a census under the assumption that the Jews were, by definition, shirkers when it came to service. When the results revealed that 80% of the Jewish recruits served at the Front, a percentage far higher than the rest of the population, the Army buried the report. It did not matter if Jews served and served bravely, the myth had taken hold—the Jews had stabbed the Army in the back. By 1919, the Dolchstoßlegenden–the Stab in the Back– had narrowed to a more familiar enemy, the Jews.

The idea of Jews being disloyal to their country was not confined to Germany. In his article, “How World War I Shaped Jewish Politics and Identity,” Paul Berger wrote,

About 90,000 Jews fought in German uniform, 275,000 Jews fought in the Austro-Hungarian army and 450,000 Jews fought for the czar. During the course of the war, these opposing armies advanced and retreated several times over the Pale of Settlement, a swathe of land on the Western border of the Russian empire where Jews had been forced to live for more than 100 years. Towns and villages were captured and recaptured several times. Each spasm of fighting brought with it new dangers and deprivations. After the Russian army was overrun by Germany, in 1915, the Russians began a retreat across the Pale of Settlement. Russian authorities saw Jews living in the Pale as a liability. As many as 350,000 Jews were either expelled or deported to the East under suspicion of providing intelligence to the enemy. The expulsions and deportations were accompanied by a wave of pogroms, characterized by rape and murder. Winter estimated that during the war between 30,000 and 100,000 Jews were killed.

This passage is interesting because the Pale was the home of one of the most famous artists of the twentieth century, Marc Chagall (1887-1985), who lived in Vitebsk, one of the cities in the Belarus region of the Ukraine. The Pale was defined in the 1906 edition of the Jewish Encyclopedia by Herman Rosenthal as, “A portion of Russia in which Jews are allowed to reside. Unlike other Russian subjects, the Jewish inhabitants do not generally possess the natural right of every citizen to live unrestrictedly in any place in the empire. Furthermore, they are permitted to leave the Pale of Settlement—that is, to move to another place for permanent or for temporary residence—only under certain conditions defined by law.” The Pale of the Settlement was a place where the Russian Empire deposited Jews and forbade them to practice agriculture, lest they compete with the Gentiles that lived there. Confined by law to establish only businesses and to participate only in trades, Jews could become wealthy. If a Jewish family accrued enough wealth, it was allowed move to other parts of Russia. Vitebsk, an old city, dating back to the tenth century, had long been a mercantile crossroads, and in the nineteenth century, the city had the distinction of being the terminus of the railroad line from St. Petersburg. This railroad was the connection between Vitebsk, one of the oldest settlements in Europe, to the rest of the world.

It was here that Marc Chagall (the French version of his Russian name, Movsha Shagal) returned from his years on Paris to attend his sister’s wedding the summer of 1914. Educated and trained in St. Petersburg, even after years of living in Paris and consorting with Cubists, Marc Chagall always remained a child of Vitebsk. A Jew, he was deeply engaged with the Jewish culture he grew up with, its myths and folklore, its social practices and its customs as carried on in Vitebsk. Cut off from the world and yet connected to it by the thread of a rail line, Vitebsk had preserved the Jewish culture of old and, in being confined to the Pale, could retain the old ways, despite the encroaching twentieth century. For Chagall, Vitebsk was a magical and mystical place, where people flew through the sky and cows had dreams, where Jewish life was wrapped up in a place of safety and peace. Chagall’s work remained deeply nostalgic for the rest of his life, keeping the Vitebsk of his youth inshrined in his imagination. Even though, from 1911, he lived in La Ruche (The Beehive) in Paris with sophisticated artists as his friends, Archipenko, Kisling, Lipchitz, Soutine, Leger, Zadkine, Pechstein, Léger, Brancusi, Rivera, Modigliani, and Delaunay, he retained the folk ways of Vitebsk in his paintings, which were structured by the Cubism shown in the Salons.

Because of the unique art of Chagall, which defied the “movements” constructed by historians, his early success in the Parisian avant-garde has been overlooked, but, of all the artists, living in La Ruche, Chagall was on the brink of establishing himself when the Great War began. There were many Russian artists working in Paris, but few who had to overcome the difficulty of being Jewish in a nation hostile to Jews. Chagall was able to quickly transform his folk art style into an up-to-date approach which allowed him to use Cubism to translate his autobiographical musings about his past and present. His new friend and fellow expatriate, Guillaume Apollinaire, called his art “surnaturel.” Within a year, his paintings were accepted to the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne, where he caught the eye of the Russian art critic, “Sillart,” or Yakov Tugendhold. Sillart wrote,

Most interesting are the works of the Russian artist Chagall. He loves the art of the Lubok (colorful narrative folk paintings). The naïveté of its composition, the wild chaotic, drunken life of the peasants in the remote villages of Lithuania (Byelorussia). On the background of toy huts and exotic nonsensical scenes of village life, an immense figure of a peasant rises, drumming on a fiddle of drunken despair. Chagall invests this figure with some higher symbolic significance. It speaks with a more lucid and expressive power than long stories about dead boredom and longing, about the dark and oppressed peasant existence. Chagall feels deeply the mystery of daily life, the abhorrent assets of the people’s life..Chagall has his own works, he gives us the truth, which sheds an original light on reality..

What makes this review, quoted here only in part, interesting is its erasure of the unique Jewish identity of “village life,” which was as Chagall depicted it only because of the anti-semitism that placed the Jews within the confines of the Pale. Anatoly Luncharsky, who would rise in the ranks after the Revolution as the “People’s Commissar of Enlightenment,” was also in Paris and wrote of “young Marc Chagall,” who “is already well-known in Paris. His crazy canvasses with their intentionally childish manners, their capricious and rich fantasy, their typical grimace of horror and considerable share of humor, unwittingly provoke the spectators’ attention in the salons–an attention that is, by the way, not always favorable.”

Marc Chagall. The Praying Jew (1914)

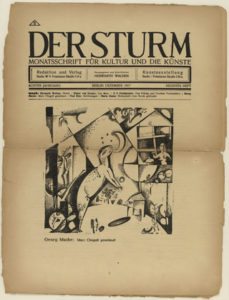

Lunacharsky did not mention the Jewish roots of the “crazy canvasses.” Neither did Swiss writer, Frédéric-Louis Sauser, better known as Blaise Cendrars, who wrote extensively on Chagall for the Berlin journal Der Strum, describing him as ” a young man, some twenty-four years, colorful himself, with strange wide eyes, peeping out under tempestuous curls–gladly shows me a countless quantity of his canvases and drawings..all elements of his of his fantasy come form the boring, crestfallen life of the lower class people of a Lithuanian suburb..Chagall is an interesting soul, though, no doubt, a sick one, both in its joy and its gloom. A young (E.T.A.) Hoffmann form a slum around Vitebsk. More precisely: a Remizov of the brush a Remizov of the Pale of Settlement. And yet, his is not a great painter..” Although the review from Cendrars is an odd one, it shares, with the others, a complete erasure of the Jewish origins of Chagall’s work. It is possible that, because there was and would be a great deal of anti-semitism in the art world, the writers did not want to acknowledge Chagall’s heritage and thus compromise the reader’s judgment of the work, which they take pains to define as “Russian.”

Issue of Der Strum dedicated to Marc Chagall

Despite the lukewarm but extensive review by Cendrars, Herwarth Walden, proprietor of Der Strum Gallery, gave Chagall an important solo exhibition in Berlin in June of 1914. It was Apollinaire who introduced Walden to Chagall in 1913, and the German art dealer probably realized that Chagall’s eccentric and individualistic paintings would have been quite interesting to German artists. Being a rare Jew allowed out of the Pale with a merchant’s pass, the artist was educated in St. Petersburg, legitimatizing Chagall. Then he had joined other Russian expatriates in Paris and became, not just a part of the Parisian cutting edge, but one of its leaders. From then standpoint of Walden, the art dealer, Chagall fit well into the avant-garde ranks. In addition, his work certainly aligned better with Expressionism than with classical Cubism and the child-like fantasies Chagall painted fed into the German fascination with alternative or outsider art, such as that made by children. In fact, when the War began soon after the exhibition, Walden sold the work Chagall left behind during the War, when it was widely and conveniently assumed that the artist was dead. Once the Berlin show had opened successfully, Chagall, on the edge of major success, took a brief side trip to Vitebsk and, when War was declared, he was trapped in Russia, a condition he referred to as “stuck” “involuntarily.” His art was also, as he described it, “stuck” in Berlin and “three big pictures” were “stuck in Amsterdam in the Salon,” while “Two other pictures remained in Brussels.” Caught behind the lines, Chagall wrote to his friend and fellow Russian artist, Sonia Terk-Delaunay, “I am longing for Paris. As to my exhibition (in Berlin), alas, against its will, it will become a prisoner of war.”

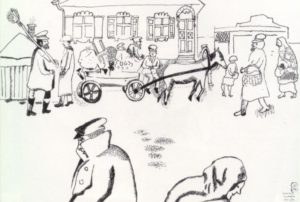

Marc Chagall. Vitebsk (1914)

Obviously in Chagall’s mind, Vitebsk was better remembered and not lived in. He married his childhood sweetheart, Bella Rosenfeld, who was apparently of a higher social status. Her family was opposed to the marriage but allowed the wedding to take place and her brother saved Chagall from duty on the Eastern Front with the Russian army. The artist became a military clerk working under Bella’s brother, who had little patience with Chagall’s lack of organization and efficiency. Without showing any gratitude for his delivery from what could very well have been a death sentence, Chagall moved to Petrograd, previously St Petersburg, and now newly renamed when the War began into something less German sounding.

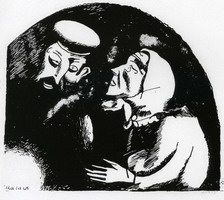

Marc Chagall. An Old Man and an Old Woman (August 1916)

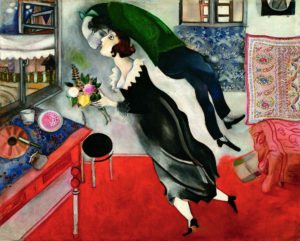

Suddenly, Chagall, who lived inside of his head and painted out of his imagination, was thrust into one of the most horrific realities of the twentieth century–the Great War. This was a war that would disgorge misery and rebellion into the streets of the city he and Bella found themselves. Petrograd was the capital of Russia, until 1918 when the capital was moved to Moscow; and, as such, the city was as cosmopolitan and as connected as Vitebsk was as isolated and disconnected behind the Pale. The city was sophisticated but familiar to Chagall, for this was where he grew up and was educated. Therefore, perhaps because of this familiarity with Petrograd, there are paintings by Chagall that betray nothing of the War except a date, 1915 or 1916.

Marc Chagall. Birthday (1916)

But there are other works that attempt to grapple with the impact of War upon people The next post will discuss the reactions of Chagall to the miseries of war and the disruptions of the rebellion against the Czar and the establishment of the Soviets in Russia.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.