The Patronage of Modernism in Vienna

One of the tropes of Fin-de-Siècle Vienna is the contradiction within the culture. The regime with its outmoded and ineffectual monarchy represented a long-dead past and the members of the court and the governing bodies of the Empire spoke in dead languages. Beneath this overlay of anachronistic social practices was a thriving counter-culture or modernism and resistance to what Karl Marx called the “dead hand of history.” This independent stratum teamed with men and women who were pioneers in intellectual and artistic achievements. Figures who would define modern life lived and worked in the same city at the same time, many of whom knew each other. Gustav Mahler (1880-1911) held the powerful post of Director of the Vienna State Opera and was the musical hinge between the past and the avant-garde future that was to come in music. He wrote nine symphonies and part of a tenth before his premature death, and, for their time, these compositions were highly experimental, making it difficult to find a musical consistency. In his interesting 2010 article on Mahler in The Guardian Tom Service wrote, “Mahler’s embracing of musical and cultural difference marks him out not as the last gasp of Romanticism, but rather as a composer of the 20th and 21st centuries. He didn’t just prefigure musical moderns like Schoenberg and Stravinsky; he was thinking and composing like an avant-garde composer. Four of his symphonies have parts for choirs and vocal soloists, and his sound-world includes everything from the quietest, most intimate instrumental lines (an offstage posthorn solo in the Third Symphony) to the loudest noises that had ever been heard in a concert hall: in a passage at the end of the Seventh Symphony, a carillon of cowbells overwhelms the orchestral instruments, an inversion no other composer could have conceived of. His symphonies live in the present tense, progressing on their nerves, each fearlessly unconventional and unpredictable.”

Emil Orlik. Gustav Mahler (1902)

Meanwhile, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) practiced a new dark art, psychoanalysis, in which the doctor listened to the patient and analyzed the language, the words used. For Freud, language whether verbal or visual, emanated from a new theoretical part of the human mind: the unconscious. The Interpretation of Dreams was written very early–1899–at the edge of the new century. With his–again theoretical–division of the conscious mind into Id, Ego, and Superego, Freud provided not just his colleagues, but an entire culture to interpret and understand personal and political and social behavior. This awareness of the mind, its vulnerability to trauma, its ultimate malleability, allowed an analyst to hear a patient’s speech acts as pointing elsewhere, to other territories, where the depths of her mind could be found. Equally famous for those of the twentieth century, searching for signposts leading to the new modern mode of understanding was the philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951) who explored the outer edges of the most arid of the philosophical branches: analytic philosophy. He lived most of his life at Cambridge teaching British students who listened to his pithy propositions with rapt attention.”The limits of my language means the limits of my world” is a very simple statement that reminds the listener that the only mode we have of expressing ourselves is the words we utter.These words are inherently limiting and we must restrain ourselves from using language to speculate and then, in an act of circular reasoning, to believe our own magical thinking.” As he said in Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922), “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889-1951)

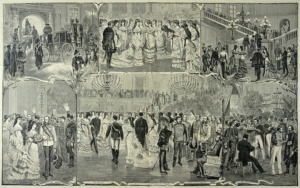

But it is of Wittgenstein’s father, Karl, who is important to the Secession building. Like Mahler and Freud, the Wittgenstein family was Jewish, placing them socially into a lower tier, regardless of talent and intellect. Writing in 1905, a certain “Lady Paget” explained the double layers of society in the Viennese culture in “Vanishing Vienna. A Retrospect.” The Lady Paget, whose complete name was Walpurga Ehrengarde Helena von Hohenthal, was a German of high birth, who served in the court of Queen Victoria and married Lord Paget. She was a well-placed eyewitness to the late nineteenth century and left behind her memories of her experiences, which, while personal, contribute greatly to the historical landscape of the Belle Epoch. Her essay on Vienna was published in a periodical and also in her book, Scenes and Memories published in 1912. “..when Viennese society is spoken of, it must be understood that it means the score or two of noble families..and that no exception is made to this rule. A second society does exist; it is wealthy and very fashionable, and said to be amusing, and some of the young men belonging to the first society frequent it. It consists of bankers, artists, merchants, architects, engineers, actors, employés, and officers, with their families. The only occasions on which the two societies meet are the great public charity balls; but even then they have hardly any intercourse.”

When discussing the first level of society, she noted that there was a split between the Hungarians and the Austrians. “Viennese society therefore consists mainly of families belonging to the German provinces and a very few from other parts of the Empire who have remained attached to the old order. Its numbers fluctuate from two to three hundred. This does not include the diplomatic corps of many high officials, civil and military, who, though bidden to Court festivities, never appear at the smaller social reunions at private houses..” She noted the strict rules for who could marry whom within the so-called “first society,” stating that “Viennese society is almost one vast family, and there are few belonging to it who are not related to nearly all the others..” Lady Paget then explains the rankings and the titles of these luminaries, stressing that “The title of baron is almost unknown in this society; it is reserved for the haute finance, and is considered specially Semetic.” As if to stress the boundaries between money of the First Society and the money of the Second Society, she wrote, “It is natural that, in a society thus composed, mere wealth counts for nothing.” If one married outside the First Society, for money, then one must retire because the rich spouse from the Second Society will not be received at court. Lady Paget also noted the unusual insularity of a society that chose to be isolated, “If an Austrian travels, which is a very rare occurrence, it is sure to be in order to shoot lions and tigers, but otherwise they are the most stay-at-home people in the world.” She concluded, “The extraordinary exclusiveness of the Austrian aristocracy is not a matter of pride; it is one of habit. The people who compose the second society would not wish to enter the first, as they would not feel at home in it, and the rare artists and literary men who sometimes are asked to the great houses are more bored than flattered by these attentions, as it obliges them to don evening clothes and tears them away from their beloved pipes and Pilsen beer.”

Vinzenz Katzler: Court ball in Vienna, 19th century, xylograph

The author wrote very little about the Second Society except to reveal the extraordinary snobbery of the era. Her essay was devoted almost entirely to the First Society, a small group of narrow minded people who would reject the outsider wife of Franz Ferdinand the heir to the throne. Reading between the lines, it is clear that the ruling classes contributed to the charities of Vienna, supported selected cultural events, but otherwise contributed little of value to the intellectual or artistic life of what was a thriving creative world, living adjacent but not deemed worthy of mention. And yet it is this Second Society that created the famous “fin-de-siècle” culture that Vienna markets and cherishes today. The largely Jewish or Jewish supported makers and shapers of culture respected, not rank or aristocracy or birth, but talent. As Alexandra Starr noted in her article, “Vienna: Trapped in a Golden Age,” ”that artists were treated as demigods..Given that foreigners and Jews were never completely integrated into high Viennese society, it’s not so surprising that their sons and daughters were particularly eager to establish a toehold in creative realms..There were few formal barriers to becoming a novelist or artist. Achieving prominence in these spheres, moreover, offered entry to a rarified world.” Writing for The American Scholar, Starr wrote of how this artistic world of intellectuals and writers crossed paths in Vienna’s famous coffee houses. “Gustav Mahler and his wife, Alma, saw Freud for marriage counseling. After Gustav’s death, Alma became Kokoschka’s lover. The so-called wild painter of the fin de siècle was a protégé of the architect Adolf Loos, who helped secure commissions for Kokoschka early in the painter’s career. The two men socialized with Arnold Schönberg, who had a separate, painful connection to another prominent Viennese painter: Schönberg’s wife, Mathilde, left him for the artist Richard Gerstl (who committed suicide in 1908 after Mathilde returned to Arnold). These interactions and bed hoppings may seem trivial, but they left a mark on Vienna’s cultural patrimony.”

Oscar Kokoschka. The Bride of the Wind (1913)

To pause momentarily to put in an aside about the painting, The Bride of the Wind, it is of interest to read what Anna Sidelnikova wrote, “In a letter Kokoschka wrote to Alma: Painting is nearing completion, slowly but all the better. We are both expressing tremendous calm, embracing, on the edge of the semicircle, the sparkling colored lights of the sea, water tower, mountains, lightning and moon. The Muse found it a masterpiece, but described it quite differently: In his large-scale painting “the Bride of the wind” he portrayed, as I trustingly clung to him in the midst of storms and towering waves – expecting him aid, while he, with a despotic face, radiating energy, humbles wave.” This emotional painting of 1913 was on a canvas cut after the measure of Alma Mahler’s bed was painted in the same year as Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque were constructing collages. Therefore Vienna, an eastern European outpost, cut off by geography from easy transit to Paris or Berlin, developed its own version of Modernism. Manifested in painting, design, and architecture, Viennese Modernism was long ignored by mainstream art history until, in 1986, the late curator Kirk Varnedoe showed New York the extraordinary visual culture of the city on the edge of the new century. In The New York Review of Books account of the exhibition at the Museum of Modern art, Carl E. Schorske discussed the very unique situation of the artists in Vienna: “The Viennese modern artists of the fin de siècle, caught between a moribund patronage system and an undeveloped commercial gallery system, marketed their products in collaborative shows, just as the French Realists and Impressionists had to do some decades before them. But the Viennese moderns, with wider cultural ambitions than their French precursors, created interior settings to present their works as elements in a Gesamtkunstwerk that would inspire in the viewer a new sense of possibility for a coherent life beautiful.”

It was a Jewish patron, Karl Wittgenstein (1847-1913) who donated the funds to support the artists of the Secession who needed a new site to show their increasingly avant-garde scandalous work. The organization the Association of Visual Artists (Vereinigung Bildender Künstler Österreichs) were led by painter Gustav Klimt and designer Koloman Moser, who persuaded artists tired of old-fashioned restrictions of traditional exhibition places and organizations, such as the Genossenschaft, to “secede,” or walk out of pre-existing institutions. The Vienna Secession existed from 1897 to 1905, and while the artists were waiting for new means of exhibiting, they launched and published Ver Sacrum, an avant-garde publication that publicized their presence and their ideas. Therefore, now that they had broke with the establishment, the artists and architects needed sponsorship.

Wittgenstein was a self-made industrialist who had literally run away from home, with a very nice violin, to America where he worked in a bar frequented by African-Americans in New York where he actually joined a minstrel band. He returned to Europe and attended, when he saw fit, the Technical University in Vienna, and left without a degree. In what seemed to be a rather wide and wandering employment record, Wittgenstein’s quality of mind would propel him to a high position in any industrial firm. The second half of the nineteenth century was the golden age of European modernization and he was the right man in the right place. When he “retired” and moved to Vienna at the end of the century, he was wealthy and owned shares in companies and factories, including the Bohemian Mining Company, the Prague Iron Industry Company, the Teplitz Steelworks, the Alpine Mining Company and many more. A bully to his seven children–three of whom committed suicide–Karl Wittgenstein was fabulously wealthy, but his entry into the artistic side of Viennese society was through his brother Paul, who was a painter. Paul Wittgenstein (1887-1961) patronized Josef Hoffmann, the up and coming modern architect and, in his turn, Karl Wittgenstein supported Joseph Maria Olbrich (1867-1908), a close associate of Hoffmann’s and a student of Wagner, on the construction of the Secession Building–a place where adventurous and creative artists could experiment and display their efforts to create new art forms that were suitable, not for a non-existent classical world, but for the century to come.

Wittgenstein Home: In the first-floor Musiksaal, Brahms,

Richard Strauss and Mahler attended the family’s musical soirées

Karl Wittgenstein both flaunted his Jewish origins and wealth in this divided society and showed off his famously straight nose in profile photographs. “There is no shame in wealth” was the motto of the man who controlled the nation’s steel supply. Although his parents had attempted to assimilate by being baptized Protestants, Wittgenstein laid claim to the repudiated Jewish background and sought acceptance into society through patronage of the arts which began around 1890. In her 2016 book, Style and Seduction: Jewish Patrons, Architecture, and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna, Elana Shapira suggested that Karl Wittgenstein was rebelling against the more genteel patronage of the other assimilated Jewish families, by cultivating the non-conformist artists which allowed him to fashion “an adopted and imagined Jewish identity.” The Second Society–artists and their patrons, who were mostly Jewish–were as hermetically sealed as the First Society. Cut off as they were from entrée into the aristocracy, this layer of Viennese culture built their own world, a world rich with innovation and invention. It can be argued that without the patronage and support of these excluded and cultivated wealthy individuals, the avant-garde world of fin-de-siècle Vienna would never have existed. At the end of the century, the world of this sophisticated city was split, between levels of society and the past and the present. Janus-faced, looking in different directions, the avant-garde of Vienna were transitional, moving away from historicism and yet haunted by the heritage of Art Nouveau. On one hand, many of the architects were functionalists, such as Otto Wagner, and yet, in response to the style of the day, they paused to coat their simple structures with decor drawn from nature. In pre-War Vienna, such design contradictions or “confusion,” as Adolf Loos might have termed it, were common. The confusion in this transition period, the pull of the past and the lure of the future, could only be resolved by living and experimenting artists. Joseph Maria Olbrich designed the Secession Building with an ancient floor plan, a modern stucco exterior that was blindingly white and plain, trimmed with softening touches of graphically drawn vegetation around the edges. An architectural compromise between ornamentation and restraint that, in historic Vienna, seemed nothing less than an affront to the Ringstrasse.

Joseph Maria Olbrich. The Secession Building (1897)

Karl Wittgenstein provided two thirds of the financing for the purchase of land and a plot on the prestigious Ringstrasse was obtained but the invasion of the modern on the turf of history was repelled. The Secession Building’s outrageously simple design outraged the Municipal Council, which refused to allow such a hulking white box to be constructed on the sacred Ringstraße. A new site on the busy but less hidebound Friedrichstrasse was selected and the proposal was approved but the building was supposed to be temporary, to be torn down after ten years. The dedication on the front of the new building named those who contributed to its erection: Rudolf von Alt (honorary president), Theodor Hörmann and Karl Wittgenstein, who was considered a co-founder of the Secession. As his daughter Hermine Wittgenstein said later, “The young organization sought patrons and found my father, who joined them as benefactor, the man they sought.” There were other benefactors from the Second Society, who preferred to remain anonymous.

The Cabbage of the Secession Building

The Secession building, designed by a young thirty-year old Joseph Olbrich, an architect younger than Otto Wagner, is almost modern in its stacking of blindingly white geometric blocks, but the corners were encrusted with floral motifs and the central block was crowned with a “cabbage,” as the natives called it, of gilded laurel leaves. Designed by Othmar Schimkowitz and Koloman Moser, the dome, to give the crown its proper name was made of 3,000 gilt laurel leaves, implying a victory over the old institutions in the race for the future. The slogan of the organization was written above the door in niche intoning the words of Ludwig Hevesi: “To every age its art, to art its freedom” (German: Der Zeit ihre Kunst. Der Kunst ihre Freiheit), but the building itself questions exactly with “age” the fin-de-siècle might be. Viewed from the side, the construction is a plan block fronted by the gilded crown presiding over the entrance where gorgons of mythological pasts reign. To the east, jutting out from the building, there is a strangely classical sculpture of Marc Anthony in a low chariot being drawn by docile lions. One entered through tall impressive bronze doors designed by Olbrich and made by Gustav Klimt. But the Arthur Strasser sculpture in its classicism and references to the antique also introduces the simplicity of the “temple of art,” as Olbrich would have it, which seems to be referencing the dome of the Pantheon. Its stacked blocks or cubed segments harken back to the Romanesque in its low solid design and the interior was a simple but always effective basilica. The Roman basilica was originally a judicial building, the interior of which was designed to be open and to provide for an efficient flow of traffic.

Back view of the destroyed Secession, 1945

As Allan S. Janik, Hans Veigl authors of the famous book, Wittgenstein in Vienna.A Biographical Excursion through the City and its History, wrote “The dissidents from the Künstlerhaus who formed the Secession really believed in the freedom of art as propagated by Hevesi and thus they reacted strongly against the reign of terror perpetrated by the state authorities in the name of historicism. They demanded a new “modern” language for art which stood in direct relation to the new sense of living that was developing around the turn of the century. Art should be supported, less by state funding, as hitherto for the most part been the case, than by collectors and patrons from the “second society.”