The First Twin Towers–The Chrysler Building (1930)

and

the Empire State Building (1931)

Part Two: The Empire State Buil

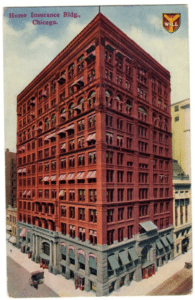

In the beginning, the architects who dreamed of tall buildings in the late nineteenth century faced the same problems as their Medieval predecessors: height and weight. The familiar formula, the higher the building the heavier its walls and the greater the weight the walls had to bear and the thicker they became and so on, meaning that like the cathedrals before them tall buildings were inherently limited. The problem was an engineering one, but it was also a materials issue as well. The cathedrals and the structures up the time of the Eiffel Tower traditionally used stone cladding of some kind. The Eiffel Tower soared because it had no cladding. Its naked skeleton straddled the Place du Trocadéro, undressed and unadorned. According to legend, it was the architect William Lebaron Jenney (1832-1907), inspired by the sight of his wife placing a heavy book on the top of a birdcage, who solved the formula and eliminated the weight problem of using the new Bessemer steel for his interior armature for the Leiter Building in 1879 and for the “Father of the Skyscrapers,” the Home Insurance Building of 1885. As any art historian knows from her study of Medieval cathedrals, it was flying buttresses or external supports which allowed for larger openings, windows filled with stained glass. A thousand or so years ago later, Jenney’s ten-story building opened up with rows of double windows for each story. As if paying homage to the cathedral, the last row of windows was arched. This detail was overshadowed by two tall stories that capped the building in 1891 with large but rather pedestrian windows.

The birdcage insight coupled with the invention of a safe elevator by Elisha Otis (1811-1861) in 1853 resulted in architecture become a sport in which engineers and builders raced each other to the top. But dreams, big and tall, require the same kind of money; and the Empire State Building of 1931 was the joint effort of important and well-heeled investors that included John J. Raskob of General Motors and Pierre S. duPont of E. I. duPont de Nemours and Company, supported by the public relations expertise of Al Smith, former politician. According to Skyscrapers: A Social History of the Very Tall Building in America by George H. Douglas, Raskob asked the architect William Lamb (1893-1952), “Bill, how high can you make it so it won’t fall down?” For the General Motors chair of Finance, the news that Walter Chrysler had decided to build the tallest building in the nation came as unwelcome news, for that had been his idea as well. Therefore, as Douglas tell the story, Raskob decided to set the height at 1250 feet, including a mast that would prove useless until it was transformed into a radio tower. Not only would the Chrysler Building be shamed but the Eiffel Tower and its Otis elevators would be dwarfed by the new structure titled “The Empire State Building.” That name, sounding grandiose but promising success when construction began in October in 1929 became a burden and a joke when the “Empty State Building” could not rent its vast spaces in the midst of the Depression in 1931.

The exterior of the Empire State Building seems to be the mundane New York City skyscraper, with a stacking of ziggurat forms that complied with the set back laws seen in the preceding tall building. But this building was one of the early expressions of Art Deco in its Americanized version and one must go beyond the graduated insets towards the top to appreciate the surface designs. The question is how? After the fifth floor setback, beyond the window washers or King Kong, who can appreciate the finer details of the vertical trimmings between the smallish horizontal windows that were lined up in a rising ribbon of glass? The architect took advantage of the prevailing style, Art Deco, which was based upon straight lines and geometric shapes, rather like Art Nouveau reformed by the sobriety of Cubism, to emphasize the height of the structure. And it is the unprecedented piercing of the New York sky that was the significant fact of the Empire State Building that seemed to rise forever, attenuating its stretch in a thin mast meant to catch a passing zeppelin. The statistics of the structure were impressive and well known: it was the first building to have over one hundred floors or stories contained in 1,250 feet made of 60,000 tons of steel. According to PBS, this cage of steel, strong, sturdy, and light-weight was clad in 10 million bricks covered by 200,000 cubic feet of Indiana limestone and granite. But this great amount of weight was surprisingly light compared to other buildings thanks to the unprecedented use of what John Tauranac termed “metal facing.” It was these ornamental trimmings that not only lessened the heft of the façade but also emphasized the zig-zag elevation.

As the author explained in his book, The Empire State Building: The Making of a Landmark that “The building was the first to employ polished metal facing for architectural as well as ornamental purposes, and it resulted in a very low ration of stone volume to building volume, an innovation regarded by architects as a revolutionary departure that foreshadowed major changes in architectural and building practice..the Empire State Building had only one cubic foot of stone to every two hundred cubic feet of building.” He described the “Chrome-nickel steel the color and texture of silver was used for the mullions that would run from the sixth to the eighty-fifth stories..chrome-nickel steel is rustless, stainless, impermeable to weather, and can be washed with plain soap and water..the mullions generally came in one length–the height of one story–and, depending on their placement, in one of two widths, ten or twenty-two inches. In addition to contributing to the upward sweep of the façade, the mullions were a critical element in the case of construction. Like the window frames, they too covered the joins.”

To this rather prosaic but informative description, one should add the classic interpretation of the Empire State Building by the writer Edmund Wilson. Reprinted from The Nation in American Earthquake, “May First: The Empire State Building, Life on the Passaic River,” his review of the new structure was an exterior one, written before the opening on May first. “There is no question that the new Empire State Building is the handsomest skyscraper in New York,” he wrote. “The first five stories, with their gray façade, silver-framed windows and lone rainlike lines in the stone, rise graceful and sheer from the street: one feels a sudden relief as one passes them–they do not crowd and overpower Fifth Avenue as most of the newer buildings do And the successive tiers fall back, each just in time not to make too heavy and dull a wall–teil the main towering shaft is reached. Seen close, the long lines of nickel facings have the look of a silver inlay, and the whole pale and silver strip might be an inlay on the pale even blue of the sky. This towering shaft, though it is the tallest in the city, has almost always an effect of lightness. From far off, the gray observation tower looks as light as it were built of shadows, its chromium cap, as it catches the sun, brittle and silver-bright like a Christmas-tree globe. In a warm afternoon glow, the building is rose-bisque with delicate nickel lines; the gray air of rainy weather makes a harmony with the brightish pale facings on their background of dull pale gray; a chilly late afternoon shows the mast like a burnished piece of silverware, an old saltcellar elegantly chased. And although in a rawer light the building looks somewhat less fine, it may still seem as insubstantial as a handful of straw-colored nabiscos stuck together and stood on end.In the cold dazing light of a winter morning, seen against a grayish-blue sky, the building has the beauty of a cake of ice, a bluish-gray block, half-translucent, with silvery gleaming edges. Only rarely, in a glaring midday, does it appear hard metallic and tool-like.”

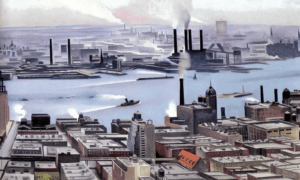

Wilson lapsed into mundane facts and figures which accompany the accounts of the Empire State Building like accessories but then he continued by describing the view from the fifty-fifth floor, painting a picture like Georgia O’Keeffe. “If you look down out of an open window, you can clearly see the water tanks on the top of other buildings; somebody’s luxurious penthouse with steamer-chairs on the roof..Below if you lean further out, you can see the straight streets of the city with the pedestrians and the motor-cars, very small, moving slowly along them. To the west, the steamboats and barges moving slowly along the Hudson; to the sound, the narrowing wedge of the island is studded and pronged at the lower end with its own growth of monstrous buildings…” Wilson then stabs the other rivals with his sharp pen: “..the Chrysler tower now dwindled, a tinny-scaled armadillo tail ending in a stiff sting-like drill, the white vertically-grooved and flat headed Daily News Building, the Luna Park summits of the American Radiator Building like a chocolate cake with goody gilt icing or a castle out of a goldfish bowl.” But Wilson is writing in the midst of a Depression, wandering through an empty building and he continues critically, “And here is the latest pile of stone, brick, nickel and steel, the latest shell of shafts and compartments, that outstacks and outmilitiplies them all–that most purposeless and superfluous of all, is advertized now as a triumph in the hour when the planless competitive society, the dehumanized urban community, of which it makes the culmination is bankrupt.” He concludes, deflating his poetic prelude by stating that “One remembers that the Empire State Building is sometimes known as ‘Al Smith’s Last Erection.'”

George Douglas wrote of the Empire State Building as a structure that was simple in concept, stating that “William Lamb was an architect whose mind ran to the pragmatic and the utilitarian; he had no interest in the excesses of art deco (in exterior detail) and refused to play around with fanciful spires, pinnacles, and other such folderol. Yet he designed a building that offered the best that art deco styling had to offer. Few buildings in New York, or anywhere, made better use of setbacks than the Empire State. The building is built to the street line for only five of its stories; the main tower is set back 60 feet offering the visitor and passerby aesthetic and psychological distance, thereby framing and setting off the building in a most pleasing way..And the design was helped out by the sheathing of Indiana limestone and granite and touches of nickel and aluminum in the spandrels and the mooring mast, all of which gave the building an ornamental building that might not have been acceptable a generation later.”

Douglas was making an interesting point. After the Second World War, the city and indeed the rest of America would be dominated by the arrival of the Bauhaus style reintroduced as tall oblong glazed upright boxes: the International Style. This building by William Lamb, as modest and self-effacing as its exterior Art Deco trimmings, slid in between the end of one war and the beginning of another. The next war would wipe away those last lingering traces of decor or ornamentation in favor of the fastidious edges of Mies van der Rohr. The modest Art Deco exterior of the Empire State Building did not date it when it was confronted with the Twin Towers of Lower Manhattan.The Empire State Building was nearly empty for years and was not filled to capacity for ten years in 1941. Over time, and certainly thanks to the Second World War, the investors were paid back and the profits began to flow, suggesting that although in real estate the key is location, location, location, timing is everything.

Georgia O’Keeffe. East River From the 30th Story of the Shelton Hotel (1928)

The Empire State Building was nearly empty for years and was not filled to capacity for ten years in 1941. Over time, and certainly thanks to the Second World War, the investors were paid back and the profits began to flow, suggesting that although in real estate the key is location, location, location, timing is everything. Empty it may have been, but the Empire State Building was anything but subtle in its interior design. To enter the building was to step into an Art Deco dreamscape, to be discussed in the next post.