PAPER: THE OTHER PHOTOGRAPHIC METHOD

Artists and Photography

The Directorial Mode

From the beginning, paper and plate had vied for being the appropriate support for a photographic image. It was by a mere series of chances that the daguerreotype gained ascendancy over paper as the favorite of the public. In January 7, 1839, the prestigious Académie des Sciences in conjunction with the Académie des Beaux-Arts at the Institut de France announced the invention of photography by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, setting off a storm of speculation and anticipation in a deluge of publicity. Although others had already invented photography based on paper, Hippolyte Bayard (1801-1887) in France and William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) in England, the combination of the imprimatur from the highest authorities in France and Talbot’s insistence on taking out a patent slowed the acceptance of paper photography. The Daguerreotype may have been limited–it was unique and could not be copied, it was reversed, it had an inconvenient mirrored surface, it was fragile and demanded elaborate protections, it was small–the public was enamored with the new invention. For ten years the silvered plate in its elaborate glass protected frame dominated not just in execution but also in expectations. A photographic image was a record, a document, a reverent replication of reality in all its astonishing detail. The surface should be smooth and unbroken, capable to absorbing all the information gained by the light pouring through the camera’s aperture.

However, in the minds of certain aspiring photographers, those very virtues of the Daguerreotype were considered drawbacks by certain photographers and there was a preference for paper in the early years and a sympathy for its unique properties with roots in the arts of sketching and printmaking. In Scotland, David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) was an already established painter with wide experience in art, who had risen to be the secretary for the Royal Scottish Academy. His best known work was sketches and paintings of the local landscapes in the Romantic Constable-like style he matured in. But in 1843, he received what seems today to be an uninspiring commission to do a group portrait of the 470 members at the first meeting of the Free Church of Scotland. At first Hill planned on doing individual sketches and then execute the painting with the long term plan of selling engravings of the work. As he wrote,

The Picture, the execution of which, it is expected will occupy the greater portion of two or three years, is intended to supply an authentic commemoration of this great event in the history of the Church … will contain Portraits, from actual sittings, in as far as these can be obtained, of the most venerable fathers, and others of the more eminent and distinguished ministers and elders.

Doing painstaking sketches of all the eminent and distinguished men would have been a daunting task, but Hill, being a member of the Free Church, was willing to try. A fellow member rescued him by recommending a young photographer, Robert Adamson (1821-1848), who was already working with Calotypes in Edinburgh. The unlikely partnership between the artistically talented older man and the technically proficient younger man resulted in the early establishment of photography as an art form that included an aesthetic sensibility controlled by the mind of the photographer, not the “writing with light” approach more akin to scientific observation. The best known series by Hill and Adamson originated in 1845 in Newhaven, a small fishing village less than two miles outside of Edinburgh. In a time of economic stress and social turmoil at mid-century, this village had the reputation of being a “model” for a self-sufficient society where the members worked together in a traditional manner.

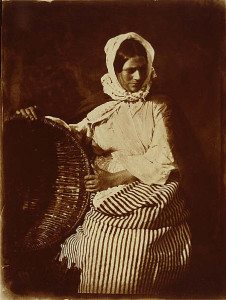

The photographers were attracted to the picturesque site and made a number of images, with the intention of publishing a book on the village of Newhaven. Adamson, the technician, made the Calotype prints from negatives, did all the printing and all the experimenting with development. Under the directorial eye of Hill, the quaint fisher folk of Newhaven were posed and photographed as if being arranged for a painting. The individuals were named in the images, but they were presented more as types, with the photographers bringing an almost anthropological perspective on a people alien to city dwellers. As the result of the paper printing process, these simple villagers were enveloped in a moody atmosphere of strong chiaroscuro, quite alien to the rough and ready reality of a fishing village on a rugged coast. While the resulting dramatic prints by Adamson were technically superb with deep tones embedded within a reddish tinted ground, the inspiration for the formal compositions was that of the artist, Hill. Due to the early death of Adamson, they worked together for only four years, and none of their projects were fully realized. The unique team left behind a legacy of thousands of photographs on paper. But Scotland was isolated and, while Hill and Adamson are interesting to today’s historians, they were not as impactful as the photographs in France who, unimpeded by Talbot’s difficult patents, were able to make great strides in improving on his Calotypes.

Hill and Adamson. Mrs. Elizabeth Johnstone Hall. New Haven Fishwife

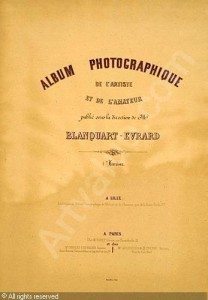

While Hill and Adamson introduced aesthetic consideration to photography, suggesting that reality would be staged, Louis Désiré Blanquart-Évrard (1802-1872) pioneered in the field of photographic reproductions. Unlike the partnership between Talbot and his former valet Nicholas Henneman in Reading, Blanquart-Évrard was a successful businessman and the reasons for his ultimate failure in producing photographic books can be accounted for as yet another instance of an idea ahead of its time unable to find a sufficient audience. Blanquart-Évrard heard of the invention of the Daguerrotype as did everyone else in France, but it was Talbot’s paper method of positive and negative that intrigued him. Undeterred by the English patent, Blanquart-Évrard, who was trained in chemistry, merely took over the process and by improving it made it his own. In a bold move, without mentioning Talbot, and with the chauvinistic support of the Académie des Sciences, he presented his findings as his own in 1847 under the title, Procédés employés pour obtenir des épreuves de photography sur papier. It is not known to what extent he was aware of the earlier experiments of Hippolyte Bayard, but, like Bayard, who dipped his paper into the silver solutions, Blanquart-Évrard also chose the soaking method, saturating the paper, in contrast to Talbot’s approach, which was to merely brush the silver nitrate on the surface.

Blanquart-Évrard should be best remembered as a pioneer technician and entrepreneur, rather than as an artist in his own right, for it was he who established a viable method of printing photographic images. His insight and achievement is remarkable given the popularity of the unprintable Daguerrotype. In contrast to the cramped development of paper photography in England, the French photographic community supported new developments and formed the Société Héliograhique in 1851, which even published a journal, La Lumière, to spread ideas and to publicize their work. Although the paper prints were reproducible and cheap, they were not favored by the public due to the lack of clarity relative to the Daguerrotype, which set the standard. An answer to the problem of the fibers of paper from another source, another member of the ever-inventive Niépce family, a cousin of Joseph, Claude Felix Abel Niepce de Saint Victor (1805-1870). Niépce de Saint Victor, as he was called, was in the military but in his spare time he continued his famous cousin’s interrupted experiments in photography. In 1847 he developed a method of using glass as a support, called the “Chebe’s de Verre” process in which the glass plates were coated with a mixture of egg whites, potassium iodide, and sodium chloride. In other words, he invented the albumen method of making a negative on glass and pioneered the idea of working with glass plates that would be fully developed with the collodion process.

Once he realized that the albumen process served his needs, Blanquart-Évrard set up a factory at Loos-lès-Lille in 1851 for printing what turned out to be a hundred thousand photographs of high and consistent quality, done in volume so that the cost to the customer were kept low. He greatly speeded up his processes by exploiting a property of photography known but not utilized, the “latent image.” Not waiting for an image to emerge on its own saved immense amounts of time. With the latent image and the improved light sensitivity of his papers, he produced strong negatives. But the public was still not convinced, and although the imprimerie was a commercial success and numerous important books of photographs were printed, the business could not be sustained longer than five years. The larger public was still in the process of learning what purpose a photograph–beyond portraiture–could serve in a modern society. The invention emerged within the realm of science and hence remained in the sphere of documentation, from the built environment to family portraits. Although the idea of books of photographs easily fitted into existing books of lithographs and engravings, the idea was ahead of the technology.

But by mid-century certain key ingredients were in place, waiting to be developed: photography was becoming part of the lives of ordinary people, and it was becoming more practical to reproduce images. In an era hovering at the edges of mass media, the question now became what kind of images to make and how these pictures should be distributed. In addition, there was ample room to expand the kinds of photography beyond a mere record into the realm of art. Accepting photography as art would proved to be a very different task. When it comes to new technology, especially something as revolutionary as photography, “readiness” is a very complicated process, trapped between what the public expects and what the audience wants. During the transition period, which usually lasts decades, there is a gradual process of education and cultural evolution. It was up to the French artists to fill in the blank spaces in the minds of the public.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.