THE WIENER WERKSTÄTTE PROJECTS

Overshadowed by the Bauhaus designs of the 1920s, the Wiener Werkstätte experiment at the turn of the century laid the groundwork for modern design. Tucked away in Eastern Europe, the city of Vienna was off the beaten path of the international art market, and, like Russia, created in its isolation a unique outlook on the arts. And yet this outpost city was very impacted, not necessarily by Germany but by a culture far away–England. The Arts and Crafts Movement, headed by William Morris, was seceded by the Aesthetic Movement, both of which attempted to elevate the role of craft and the status of the artisan in an age of industrial manufacturing. The answer to the production of fake elegance was to “reform” design and to restore the primacy craft had enjoyed during the Medieval period. Based upon the aesthetics of the cathedral where all the arts were seamlessly combined into one experience, the English artists sought a Gesamtkunstwerk or total work of art. As noted in earlier posts, the idea of daily life becoming aesthetic, or elevated to an experience that brought art into everyday life. In Vienna, decades later, these ideas of integrating elegant works of art into the domestic sphere were taken up as articles of faith by the artists of the Secession. This new organization, which seceded from the traditional official agency for showing works of art, combined painters, sculptors and designers and other artisans in their exhibitions. Six years after the founding of the Secession, the Wiener Werkstätte began operation in 1903 as an independent business specializing in hand-crafted modern design. In late 2017, the Neue Galerie mounted a retrospective of the Workshops, listing a number of participants not was well known: Gudrun Baudisch, Carl Otto Czeschka, Berthold Löffler, Arnold Nechansky, Michael Powolny, Felix Rix-Ueno, Max Snischek, Vally Wieselthier, Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill, and Ugo Zovetti. In the review of this exhibition, Jason Farago of The New York Times wrote, “None of this came cheap. Vienna in the early 20th century was an imperial capital — Hoffmann moved there from what is now the Czech Republic — and home to a new haute bourgeoisie whose members, many of them Jewish, became enthusiastic clients. Still, the workshop’s insistence on the best materials elevated expenses, as did the handsome salaries of the artisans, who stamped their monograms on their metalwork, fabric printing and book bindings. High production costs meant high retail prices, and that meant putting artistic ego to one side. Hoffmann’s statement at the end of the Wiener Werkstätte’s manifesto put it plainly: “We are not allowed to chase after daydreams. We have both feet firmly set on the ground, and we need commissions.’”

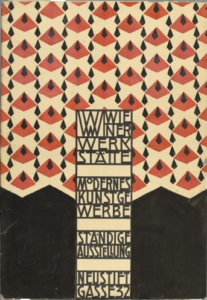

In his book, Graphic Design: A New History, Stephen Eskilson explained the process of what we today would call “branding,” or creating a recognizable design that would be identified with the Wiener Werkstätte and not with its precursor Art Nouveau. “In terms of style, the artists associated with the Werkstätte rejected the irregular, organic curvilinear style of the early Secession and focused their efforts on the geometric clarity of form that thad become a major part of Secessionstil around 1900. All of the products of the Werkstätte were harmonized to fit this restrained style, a style that was in a way summarized by the two logotypes produced to adorn the good in 1903. In tune with the medieval spirit of collaboration that had characterized the Arts and Crafts movement in England, it was never revealed whether Moser or Hoffmann had designed the logos of it they were a communal project. The “rose” logo features the eponymous flower depicted in a severe rectilinear design,its bloom made up of squares within squares, each part of the flower boxed in by a rectangle. The “Twin Ws” logo displays the superimposed letters in a perfectly square shape, essentially an em box (content area) around the letters. An important part of the Werkstätte ideology was that the designers, most of whom were graduates of the Kunstgewerbeschule, would be paid royalties from their work, and not have to suffer the lowly status and desperate poverty of wage laborers. The square shape that is a distinguishing characteristic of many Werkstätte designs was employed equally by Moser and Hoffmann, although the latter used it so prominently that it became known by the nickname the ‘Quadratl-Hoffmann.’”

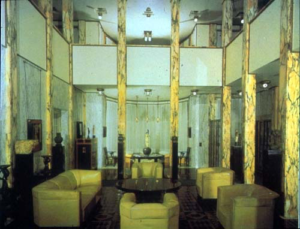

Josef Hoffmann, Original Design for Opening of Wiener Werkstätte Showroom (1905)

The Werkstätte depended completely on wealthy and discerning clients for whom price was no object. While such individuals existed, the cost of crafting the wide variety of products exceeded the customer base. During the halcyon days before the Great War, maintaining the Workshops seemed plausible but the arguments about the practicalities of cost clashing with the ideology and ideals of the organization caused Koloman Moser to leave after just few years. The production was done in the 7th district of Vienna at Neustiftgasse 32-34, where a new building was fitted out for the purposes of the Werkstätte. Before the fortune of the patron Wärndorfer was exhausted trying to support the high-priced enterprise with its insistence on the highest quality materials, the Workshops had several branches in Germanic sites: Karlsbad in 1909, Marienbad and Zürich between 1916 and 1917, New York in 1922, and finally Berlin in 1929. One of the first commissions sounded unglamorous and undesirable, but the Sanatorium Purkersdorf, was actually a rather elegant establishment for privileged individuals, especially the elderly, who needed a quiet but luxurious place to recuperate from physical and mental illnesses. Hoffmann, once a student of Otto Wagner, was commissioned to design and furnish the entire building in 1904-05 by the industrialist Victor Zuckerkandl. Another remarkable patron, the steel magnate Zuckerkandl associated with the Bloch-Bauers and the Lederers, and along with his friends supported the painter Gustav Klimt. His brother Emile, a university professor who signed a petition to retain the infamous “university” paintings, “Philosophy,” “Medicine,” and “Jurisprudence.” These controversial paintings were purchased by a gallery and during the Second World War, were put in storage for safekeeping. But they were destroyed by a fire in 1945. Likewise, only a few of Zuckerkandl’s collections of Klimts survived the War and Nazi looting. The rest of the paintings have disappeared and the Sanatorium remains as an important legacy for the industrialist.

Because of the presence of a spring on the property, the sanatorium was designed to be a “mineral spa along with a healing park.” This institution was very elegant and very luxurious and only the most privileged invalids came to Purkersdorf, including composer Gustav Mahler, the dramatist Hugo von Hoffmannsthal, composer Arnold Schönberg and playwright Arthur Schnitzler and a contingent of international millionaires. The interiors were decorated by the members of the Werkstätte and it is here that it is possible to see some of the early designs that would become so characteristic of the Workshops. Hoffmann used the very modern construction techniques of reinforced concrete that contrasted with the discrete and very rectilinear design in the interiors. Given the building’s purpose, emphasis was put on openness for ease of surveillance of the mental patients who were given three levels which separate the three aspects oft their treatments: physiotherapy, community activities and bedrooms were located on three different levels. The color scheme was simple, white enhanced by black accents, creating a restful light filled interior space that refused a clinical appearance and was so stylish, the Sanatorium looked like a very elegant hotel.

In her book, Historical Dictionary of Architecture, Allison Lee Palmer briefly described Hoffmann’s work: “Hoffmann’s Purkersdorf Sanatorium, built in 1904, on the edge of the woods outside Vienna was commissioned by Victor Zuckerkandl to be a modernist nursing home for the wealthy elderly. Zuckerkandl dictated much of the design and in fact wanted a flat roof for the building. The building is a simple, white rectangle cut inward and outward to create cubic volumes that provide a three-dimensional façade together with a three part vertical division of the exterior. The rhythmic arrangement of unarticulated rectangular windows, grouped in threes, reveals a restrained well-proportioned structure. the bright, white interior, done in a very national style, cultivates the appearance of a ‘sanitary’ space. Hoffmann’s subsequent Palais Stoclet, constructed in 1905-1911 in Brussels for the wealthy banker Adolphe Stoclet, was designed in a much richer style called the Jungenstil, the Viennese version of Art Nouveau style. Copper sculpture decorates the exterior of this subtly historicizing, organic building, while the interior is decorated with murals by Gustav Klimt. This is the style that provided the impetus for Loos’s attacks on architectural ornamentation and excess.”

The two commissions by Hoffmann indeed provide an interesting contrast between institutional restraint and the opulence of a private home in Brussels. The strict cubic segments of the Sanatorium were outlined by narrow strips of blue and white checked tiles which served to emphasize the edges. Something of the same idea was deployed on the Palais Stoclet with the outline of the structure reiterated as if punctuating the flatness of the geometry. Inside the impact of Charles Henry Mackintosh was evident in the squared off furniture of the Purkersdorf ranged from opened cubes transformed into low square chairs to the tall perforated backs of chairs used around dining room and meeting tables. While the walls of the Palais were either marble or painted with elaborate murals by Gustav Klimt, the white walls and ceilings of the Sanatorium were marked with linear woodworking, a simple way of maintaining a theme of simple geometric shapes. The feud between Hoffmann and Loos mentioned by Palmer was a particularly bitter one, mostly on the side of Adolf Loos who needed a sparring partner and a famous architect with an impressive pedigree would make a worthy foil. But the extremes preached by Loos in his 1908 book Ornament and Crime belied the revolution of the Wiener Werkstätte designs.

Purkersdorf Sanatorium Interior (1904-05)

In his interesting article “Trapped in Vienna” in The New York Times Book Review, Andrew Butterfield noted the divided feelings among the creative talents in the city. Yes, they were living among and creating a seismic shift in taste, but the arts were supported by the outsiders, the Second Society, and the artists struggled between this narrow and precarious patronage base and the rejection of the larger part of society. The only way out of the isolation of Austria, a nation on the outpost of Eastern Europe, headquarters of an aging Empire was to physically exit. As Butterfield wrote, “The endless conflict, the extreme isolation, and the intense claustrophobia drove many artists and musicians away from Vienna. Klimt said to Berta Zuckerkandl in 1905, ‘I want to get out,’ although he in fact decided to stay. Mahler left for New York in 1907, Schoenberg went to Berlin in 1912. As Hofmannsthal wrote, ‘We must take leave of the world before it collapses.’” The author concluded on the now familiar note–the fate of the art in Vienna supported by Jewish patrons–their persecution at the hands of the Nazis. Amalie Zuckerkandl of the famous family and subject of a lovely unfinished portrait by Klimt “was murdered by the Nazis in a concentration camp in 1942. Her intelligent, glittering, bewildered eyes gaze out of her face, asking us to remember and to understand.”

Palais Stoclet from the East, Brussels (1906-11)

In an article on the Palais Stoclet in the Wall Street Journal, Michael Z. Wise described a home that is probably the most complete manifestation of the Wiener Werkstätte and the Vienna Secession. As Wise said, “Belgian banker Adolphe Stoclet and his wife, Suzanne, wanted a home that was a shrine to art, a sumptuously appointed abode where nothing would be left to chance. After the Palais Stoclet in Brussels was completed a century ago, designed by Josef Hoffmann and embellished by a cavalcade of Viennese artists, a guest described it as having ‘the enchantment of one of the basilicas of Ravenna.’” The designers, led by Josef Hoffmann, were given carte blanche and to this day the final price tag for the design, exterior and interior, is unknown. Wise continued, “Hoffmann, founder of the Wiener Werkstätte artistic collective, drew up the geometrically refined exterior clad in white Norwegian marble with undulating gold-leafed trim; Werkstätte members including Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser and Michael Powolny brought splendor to the interiors. The designers placed every item within the house and its grounds, supplying specially created artworks, gardens, furniture, light fixtures, cutlery and silver toilet articles. For the dining room, Klimt crafted a dazzling marble mosaic encircling a table with 24 chairs. Silver candleholders and tureens studded with malachite cabochons sit atop polished ebony sideboards. Chandeliers strung with pearls heighten the magic. All is intact as on the day the Stoclets moved in. “It seems as if it were still 1911,” said Alfred Weidinger, deputy director of Vienna’s Belvedere Museum. ‘You don’t sense the passage of time.’”

Aaron Betsky explained that behind the gray walls of Norwegian marble gracing the exterior of the Palais was a feast for the eyes and the senses, describing the home as a “gilded cage.” He said, “..every inch of every surface in the Stoclet—carried out by the artists of the Wiener Wertkstätte—is marble, gilt, South American hardwood, or something else precious. Pretentious and overbearing, the Palais Stoclet is one of the most beautiful examples of architecture that asserts itself as something expensive, based on abstract principles, and enforcing its logic on our daily lives..The sensuousness of the textures, culminating in the 20-foot murals that Gustav Klimt created to grace the walls of the dining room, conflates Ali Baba’s treasure cave with a built version of haute couture: you surround yourself with visible wealth and luxuriate in it. Every moment of parquetry, marble, onyx, or hardwood is itself an exercise in geometry carried out in a dizzying variety of patterns..Everywhere you look, every aspect of life, from how you sit to what you see, has become an example of human ability to craft a complete environment. The axes lead nowhere except back to more rooms where you once again bathe in perfectly ordered and contained luxury. Even the views into the garden only give back clipped hedges giving no escape, but continuing the axes to a limited outside area.”

Adolphe Stoclet was one of the many patrons for the Werkstätte, and in fact at the end, the main support for the Workshops. But as with the other rich industrialists who wanted to contribute to the arts and culture of their time, their mission and their genuine love of exquisite craft would live long after each one of them. Like the Purkersdorf, great care has been taken over the decades to maintain the original intnet of the designers. As reported earlier, the Palais is the same as it was one hundred years ago, a bit neglected, except for pilgrims, many of whom come to see Klimt’s last great frieze. In the book Gustav Klimt:1862-1918, Gilles Néret explained how the commission came about: “While Adolphe Stoclet, the Belgium industrialist, was living with his wife Suzanne Stevens in Vienna, he gave the contract for the new house in Brussels to the Vienna Workshop, to Josef Hoffmann and Gustav Klimt. ‘The commission,’ explains Hoffmann, ‘was to use architecture and new motifs to replace old styles, and to find the right form and minimum proportions for maximum utility with the greatest precision possible..The painter will be called upon to decorate the interior. He will no longer be obliged to’ paint figuratively, but will be able to express his ideas directly in shapes and colors, without recourse to narrative details.’”

In some ways, the Wiener Werkstätte the last manifestation of craft and art as luxury items for private use and enjoyment. The future would be for the masses, who would need cheap housing of good design constructed with affordable materials. The post-war generation of designers from the Bauhaus and architects such as Le Corbusier would take the ideas and lines of Werkstätte forms. The industrial machine aesthetic reveled in plywood and tubular steel, reiterating what had once been done in the most precious of materials and with the most exquisite care on the mass production line. Finished just before the Great War, the Palais Stoclet put a period on what had begun as an effort to create a modern design ethos for the twentieth century. While the ethos towards luxury could not survive, the skeleton of the basic design concepts remained behind: the definitive shift away from the curvilinear undulating line of nature to the straight controlled lines of culture. A Koloman Moser chair is excessive to be sure but the designer also elaborated on a simple theme: the chair as a cube. But it would be the cube the simple square squared that would the basis for architecture for the twentieth century: basic post and lintel construction pf reinforced concrete. That was the future coming out of the past.