Timothy O’Sullivan: Exploring the West

Part One

In retrospect, it is something of an oddity that twenty-one year old Timothy O’Sullivan was not drafted into the ranks of the Union Army for the American Civil War. After all many young Irishmen, fresh to the shores of their adopted country voluntarily joined the military in hopes of quelling the rising anti-Irish sentiment in the Northeast towards foreigners. But O’Sullivan found another role for himself in the terrible war, as assistant photographer to Alexander Gardner, covering the aftermaths of battles and making a unique record of the waging of the first modern industrialized conflict and it unimaginable costs. The point may seem a small one–O’Sullivan did not fight in the Civil War—but his point of origin is uncertain and it is not known where he was born. At one point, the photographer claimed that he was born in America, but upon his death, his own father noted for the official record that his son, an obscure documenter of the American West, had been born in Ireland. And it seems more than probable that the elder Mr. Sullivan was correct: if Timothy O’Sullivan had been of Irish descent and born in America, he would have been drafted and we would remember the Civil War in a far different fashion. Along with Gardner, O’Sullivan made iconic images, once long-lost and forgotten, of a tragic war are now an indelible part of our national psyche. Only two years later, O’Sullivan embarked upon another groundbreaking journey, going into remote corners of a vast desert territory in the American West, in the employ of a man in search of catastrophes.

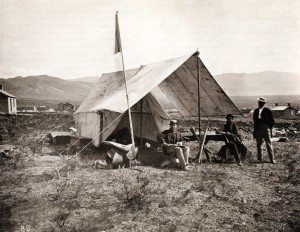

Clarence King, Salt Lake City, Utah Camp, October 1868

That man was Clarence King (1842-1901), who had also not served in the military during the Civil War. His reasons for not being a soldier seem to be somewhat different. The facts are sketchy, but, given that this young man was once arrested and charged with being a “draft dodger” and given the fact that the case was dropped, suggest that the wealth and privilege of his family exempted him from service. Although the Civil War was a highly emotional conflict and we remember it as being a morally driven cause on both sides, the actual potential combatants were hardly enthusiastic about serving. Like the Viet Nam war, one hundred years later, the privileged young men could avoid the war, while the lower class males–who really had no economic stakes in play–bore the burden. While O’Sullivan was roaming the killing grounds, Clarence King was studying geology and acquainting himself with the scientific debates of his day. On one hand, King was an intellectual and an academic, on the other hand, he was a bit of an adventurer and a believer in the manifest destiny of America, which would be carried forward on the tracks of railroad lines. The Yale graduate of the Sheffield Scientific School became the leader of the Survey of the 40th Parallel at a time when the surveys of the unchartered sections of the West were transitioning away from the military and into the hands of scientists. The goal was not military conquest but conquest through scientific marking and a study of the geology, the natural resources and mineral wealth that coincidentally lay along the route of the railroad. As King later remarked, “Eighteen sixty-seven marks, in the history of national geological work, a turning point, when the science ceased to be dragged in the dust of rapid exploration and took a commanding position in the professional work of the country.”

O’Sullivan, an experienced photographer, was, for all intents and purposes, a valuable member of the crew that worked with King. While the scientists and geologists collected specimens and made scientific observations and recordings, the role of the photographer was to make visual records of the typology, the landscape, the vistas, the details of the terrain. It was not his job, for example, to photograph flora and fauna or insects or the animals killed and turned into artifacts. O’Sullivan photographed the land itself and here is where his task transcends mere objective record and metamorphosed into something quite different, resulting in a body of dramatic photographs, flattened vistas composed of shapes and shadows and edges, suggesting to modern eyes an almost abstract view of terrain. Although O’Sullivan worked with King for three seasons from 1867 to 1869, the Survey leader seems to have made sparing use of the photographs which do not seem to have been given any more value than any other artifact collected during the project. O’Sullivan’s work with King was intermittent and he also spent several seasons with the (Lieutenant George) Wheeler Survey of the 100th Meridian during 1874, 1875, and 1876. During his tenure with the Wheeler Survey, O’Sullivan was working with photographer William Bell, who would be given less responsibility than the Irishman, perhaps due to his less experienced status. These images were published in an album, which according to Lauren Higbee in her article on “The Wheeler Album: Photographic Rhetoric and the Politics of Western Expansion,” was “a site of political maneuvering amongst the above participants as well as a political toolwielded by Congress to legitimize its policies in post-Civil War America amid a time of great political corruption and upheaval.” Higbee looked at that album as an “exhibition,” if you will, of the government funded project and functioned as both an advertisement of accomplishment and a scientific showcase of an unknown region of the nation.

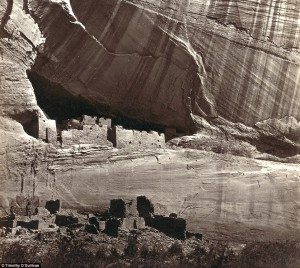

Timothy O’Sullivan.View of the White House, Ancestral Pueblo Native American (Anasazi) ruins in Canyon de Chelly

In fact, the body of work produced by O’Sullivan faded from memory and was stored away until seventy years later the photographer Ansel Adams stumbled across O’Sullivan’s landscapes. According to a 2008 article by Britt Salvesen, then of the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona, Adams had acquired an 1874 album from Sierra Club officer Francis Farquhar. This album was the Geographical Explorations and Surveys West of the 100th Meridian, a record of Wheeler’s Survey, which O’Sullivan joined between sessions with King. Perhaps the most famous of the images by O’Sullivan was that of Canyon de Chelly, a striking cliff face in New Mexico. Later Adams himself would retrace the footsteps of O’Sullivan and photograph the site from the same vantage point on his own, but formally speaking, O’Sullivan was seen as a precursor of modernism and placed in the emerging photographic canon. Although those art historians who are more interested in historical context and social conditions are less interested in the O’Sullivan-the-modernist narrative, the photographer still holds a privileged place in the photographic pantheon and this elevation is still based upon the striking visual nature of many of his works.

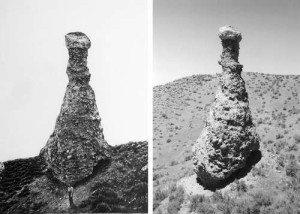

Timothy O’Sullivan. Vermillion Cañon, Colorado (1872)

By the 1930s, photographers were used to skewed views of the landscape, odd oblique camera angles and unexpected vantage points and O’Sullivan’s photographs were seen within this new context, a context that did not exist when he was working for King and later for another military and mapping survey, for Lieutenant George Wheeler in 1869. Adams called the prescient images taken by O’Sullivan to the attention of Beaumont Newhall of the Museum of Modern Art, and Newhall included O’Sullivan in his centenary (and landmark) celebration of photography, “Photography: 1839–1937,” held in the Spring of 1937. Salvesen mentioned that Adams interpreted O’Sullivan’s work in light of Surrealism, a movement now waning. (There was also the body of Surrealist photography that was emerging from this current movement, but the exact reference of Adams is unclear and he probably was speaking metaphorically). Thanks to the newly established department for photography at the Museum there would be a genuine and on-going attempt to build a historical archive for American photography which would lead to previously ignored works being rediscovered and reconsidered, including O’Sullivan, whose work was also admired by Alfred Stieglitz.

Is is unclear, in 1937, the extent to which the full range of the photography of the West was either known or understood, and it is also unclear if Adams or Newhall understood the extent to which O’Sullivan’s work was “strange,”so to speak, compared to his contemporaries. But Adams apparently sensed something different about what O’Sullivan had done for the survey parties and the term “surrealism” became a handy trope to connote the strong and striking difference between these prints on albumen paper and those by William Bell or William Henry Jackson. But to call any of the photographers of the Western surveys “art” photographers would be incorrect. These were professional photographers, hired hands, following instructions, but they had apparently incorporated, if only through a cultural and visual osmosis, the language of landscape painting and the artifices, such as making sure there is a repoussoir in the foreground and a recession into a vast expanse, all framed in a proper Claudian structure, then three hundred years old. Even though photography was supposedly a record of the real, the observed, the devices used by painters to suggest an illusion of depth, were repeated by the landscape photographers who used the known and the familiar to situate the viewer, even, as in the Western views, the scenes were so unfamiliar they bordered on the “surreal.” The extent to which O’Sullivan deviated from the established norm, ignoring all landscape conventions, was noticeable in the late 1930s but it was the work of re-photographer Rick Dingus forty years later that demonstrated the originality of the work of Timothy O’Sullivan.

Headed by Mark Klett, who was working with protohistorian Ellen Manchester, and sponsored by the National Endowment of the Arts and the Polaroid Corporation, the Rephotographic Survey Project was active between 1977 and 1979. JoAnn Verburg was the research coordinator who led the photographers, Rick Dingus and Gordon Bushaw to the exact locations–site, time of day, time of year–where nineteenth century photographers, William Henry Jackson, John K. Hillers, Andrew J. Russell, and Timothy O’Sullivan, once stood photographing the West. On the surface, the Rephotographic Survey Project was a simple retracing of the steps of the originators of Western photography to see how the land had changed, had become overgrown by tourism and otherwise modernized or not, but for a photographer, rephotographing these sites was a chance to analyze the decisions made by their precursors. Carleton Watkins, it is well known, established conventional “views” or the best vantage points for the visitor to Yosemite, but the survey photographers were recording a process of scientific investigation–O’Sullivan’s brief–or a period of technological conquest–the work of A. J. Russell, and it was far from certain that their images would ever find their way to a broad public audience. The intended audience was corporate and political and the often pedestrian language of the pictures reflects that expectation on the part of the employers that the images should be descriptive accompaniments to a more precise discussion provided by proper scientists.

Rick Dingus found that O’Sullivan seemed to be working under a different set of instructions, and in doing so he opened up a new discourse on Timothy O’Sullivan, seemingly adding to the thesis of Ansel Adams and Beaumont Newhall–that Timothy O’Sullivan was a photographic formalist, an abstractionist, avant la lettre. But other perspectives on the photographer would emerge over the ensuing decades. It is these “pure” landscape photographs that are of most interest to historians. But how “pure” are these landscapes by Timothy O’Sullivan?

In his 1994 article, “Territorial Photography,” Joel Snyder noted that the standard and established use of photographs as “integumental likeness–as passive recordings of preexisting sights.” This passivity and mirroring, not just of what could be seen but of what the audience expected to see, responded, Snyder suggested to the expanding interest in documentary photography. The author related how photographers of the West could find an audience to view and to purchase their views, indicating that these operators were aware of the commercial need to please the customers. But Snyder’s point was more subtle than mere horizon of expectations, he was suggesting that photographs were intended to respond to and to create a collective way of seeing, something he called “distributed vision” or “disinterested” seeing that transcended the individual. These conventions of viewing photographs of the West, based on paintings of the past, were augmented by implied promises of new beginnings in a supposedly virgin land, full of possibilities and ripe for exploitation.

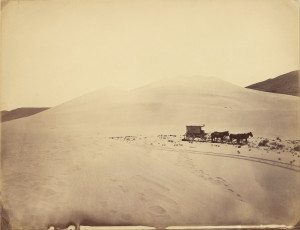

But Timothy O’Sullivan produced a body of counter-images, termed by Synder, as “contrainvitational,” expressing the inherent “hostility” of desperate deserts and high hard rocks of the West. If Snyder is correct, we might assume that because his photographs were intended for a more limited audience, O’Sullivan seized the opportunity to photograph the West in a fashion that foregrounded the unknown. This land was, as Snyder put it, “terra incognito, as a world different from ours, unfamiliar, inhospitable, and terrifying.” Snyder concluded: “O’Sullivan’s photographs, then, are not to be understood as scientific documents, but as something like pictorialized ‘No Trespassing’ signs.” Was it the intention of O’Sullivan to create a vision of forbidden places, too dangerous for the tourist, much less the aspiring settler? We know, as Snyder points out that O’Sullivan, as he had done during the Civil War, manipulated the photographic outcome for dramatic effect, highlighting a stray sand dune to suggest an engulfing desert, but how do his actions–carried out in the midst of scientific exhibitions–square with the idea of a truthful survey of unmapped territory?

Desert Sand Hills near the Sink of Carson, Nevada (1867)

The next post will continue to examine the debate around the intentions of Timothy O’Sullivan and the interpretations of his oeuvre.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.