Pre-War Modernism in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna

The Last of the Old: The Ringstraße

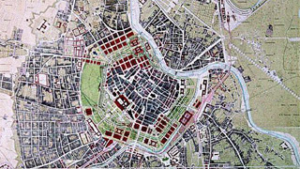

To understand Vienna, the heart and soul of Austria, the seat of the aging but glitzy Austro-Hungarian Empire, it is necessary to understand the Ringstraße, an urban development project that had significant cultural and social consequences for Vienna. The Emperor Franz Josef grasped the social goals of the French Emperor Napoléon III in renovating medieval Paris–move the lower classes to the perimeter and shift the class in power, the middle class, to the heart of the city. Like Paris, Vienna had been plagued by internal insurrections and replacing the medieval walls surrounding the city with magnificent buildings provided a barrier placed between the classes. The lower classes simply could not afford to live in this new luxurious suburb and was relegated outwards to the Viennese version of the Parisian banlieu. In July 1858 the competition for designs for the architecture for the Ringstraße closed with eighty five entries. The three prize winners were architects from the Akademie der bildenden Künste in Vienna. As Thomas Hall pointed out this was “the first major ‘modern’ town planning competition appears to have been arranged along lines that are surprisingly similar to the way such things are organized today.” The following year, a Grundplan was begun and actual construction commenced in 1860. In his book, Planning Europe’s Capital Cities: Aspects of Nineteenth-Century Urban Development, Hall also noted that in the 18690 the Baroque style was considered the appropriate style for “the seat of imperial power.” He continued, “..it was not possible in Vienna to create the same straight streets and long integrated prospects. Both the shape of the Ringstraße–an irregular hexagon–and the trees that line it, preclude the idea of uninterrupted vistas.” Instead of the straight boulevards of Paris, Vienna has clusters of buildings united by the Ringstraße, which, as Hall stated “gives the area unity.” Although because of its huge size and disparate needs, the Ringstraße had to be a collaborative enterprise, “the Ringstraße as a whole–perhaps uniquely in our material–is a Gesamtkunstwerk, an example of ‘total art’ in which architecture, landscape architecture, sculpture and even interior decoration come together to create a unified setting, a true expression of the aesthetic, social and political values of the times.”

Project for the Ringstraße 1860

In the article “Viennese Modern Design and the Taste for Living,” Joann Skrypzak noted that the Ringstrasse stimulated artistic development in the city. “It drew many artists to Vienna and provided them with training and employment from which they expanded or departed. In 1861 during the Ringstraße development the emperor founded the city’s one exhibition facility for contemporary art known as the Künstlerhaus. This institution was meant to present the work of living artists and promote cultural exchange with other European countries, an aim similar to that of its later rival, the Secession. Although predicated on democratic rule, the Künsterhaus came to be dominated by a conservative majority that left little room for the younger generation for avant-garde artists.” Therefore, part of the importance of the Ringstraße was the negative reaction to what was immediately criticized as architecturally backward. As the decades progressed, young architects in the city measured themselves in terms of the Ringstrasse–they were opposed to the edifices and everything they stood for.

To put it simply in twenty-first century terms, the Ringstraße was a large multi purpose urban development but as the historian Carl Schorske (1915-2015) pointed out in his book, Fin-De-Siecle Vienna: Politics and Culture, this inner city renewal was freighted with social, cultural, and political meaning. On the surface when it was planned in the 1860s, the Ringstrasse seemed to epitomize modernism, the kind of modernity that could be compared to the rebuilding of Paris under Baron Haussmann during the Second Empire. In terms of construction and conveniences and life style, the Ringstrasse was modern and up to date, technologically speaking, but the architectural style was as eclectic as that of the boulevards of Paris–new but traditional, evoking the past while building the future. Indeed, as Schorske noted, the Ringstrasse celebrated the rising middle class, cemented its power, and centered its most august representatives in the heart of the city, just as the “Haussmannization” of Paris swept out the historical inhabitants, the lower classes, and replaced with them with the newly wealthy.

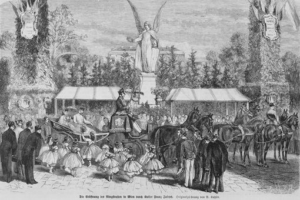

Opening of the Ringstrasse by Kaiser Franz Joseph on May 1, 1865

In 1961, Schorske wrote:

In 1860, the liberals of Austria took their first great stride toward political power in the western portion of the Habsburg Empire and transformed the institutions of the state in accordance with the principles of constitutionalism and the cultural values of the middle class. At the same time, they assumed over the city of Vienna. It became their political bastion, their economic capital, and the radiating center of their intellectual life. From the moment of their accession to power, the liberals began to reshape the city in their own image, and by the time they were extruded from power at the century’s close, they had largely succeeded: the face of Vienna was transformed. The center of this urban reconstruction was the Ringstrasse. A vast complex of public buildings and private dwellings it occupied a broad belt of land separating the old inner city from its suburbs. Thanks to its stylistic homogeneity and scale, “Ringstrasse Vienna” has become a concept to Austrians, a way of summoning to mind the characteristics of an ear equivalent to the notion “Victorian” to Englishmen, “Gründerzeit” to Germans, or “Second Empire” to the French. Toward the close of the nineteenth century, when the intellectuals of Austria began to develop doubts about the culture of liberalism in which they had been raised, the Ringstrasse became a symbolic focus for their critique. Like “Victorianism” in England, “Ringstrassenstil” became a quite general term of opprobrium by which a generation of doubting, critical, and aesthetically sensitive sons rejected their self-confident, parvenu fathers. More specifically, however, it was agsisnt the anvil of the Ringstrasse that two pioneers of modern thought about the city and its architecture, Camillo Site and Otto Wagner, Hammered out ideas of urban live and form whose influence is still at work among us..The contrast between the old inner city and the Ring area inevitably widened as a result of the political change. The inner city was dominated architecturally by the symbols of the first and second states: the Baroque Hofburg, residence of the emperor; the elegant palais of the aristocracy the Gothic Cathedral of St. Stephen and a host of smaller churches scattered through the narrow streets. In the new Ringstrasse development, the third estate celebrated in architecture the triumph of constitutional Recht over imperial Macht, of secular culture over religious faith. Not palaces, garrisons, and churches, but centers of constitutional government and higher culture dominated the Ring. The art of building, used in the old city to express aristocratic grandeur and ecclesial pomp, now became the communal property of the citizenry, expressing the various aspects of the bourgeois cultural ideal in a series of so-called Prachthbauten (buildings of splendor)..

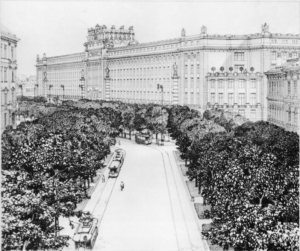

The Ringstraße or Ring Road had some of the same pomp of the grand boulevards in Paris, but the Ringstrasse was, as its name stated, a “ring,” and laced the straight-line perspectives of Haussmann’s city of surveillance. And yet the wide, easily traversed thoroughfare in Vienna offered the same convenience, allowing troops to be moved swiftly from one part of the city to the other. The building and its Prachtbauten or “magnificent buildings” of the Ringstraße, like its total impact, took several decades and, when it was completed, the architecture faced an entirely new generation which scorned tradition and historicism and stylistic hybridity. The up and coming architectural critic, Aldof Loos condemned the structures with their imposing façades as “Potemkinstrasse.” Loss used the term to indicate the idea of a façade hiding emptiness, in this case, the architect would have been referring to style. as Julia Teresa Friehs pointed out in her article, “Historicism–The Architectural Style of the Ringstrasse,” the “style” of the Ringstraße was historicist, a ménage of past styles with signifiers of power and stability, hiding updated technology that made the buildings functional according to modern needs. As she wrote, “Theophil Hansen (1813–1891) designed the Parliament building in the Hellenistic style, in the belief that the form of government in classical Athens had given birth to the truest form of democracy. The neo-Gothic City Hall by Friedrich Schmidt (1825–1891) reflected the civic autonomy of the cities in Flanders. The Votivkirche by Heinrich Ferstel (1828–1883) was built in the French Gothic style, while in his designs for the university Ferstel took as his model the Italian Renaissance, the period when art and science flowered in Europe.”

Otto Wagner, War Ministry on the Ringstrasse, Vienna.

Wagner’s buildings were intended to facilitate the movement of the street

Because each architect had total control over each building, he had to coordinate the inside design with the exterior style. But more than totality or consistency of concept, the idea of artistry was important and the architect’s task extended to creating a Gesamtkunstwerk. Of course, such a massive construction project triggered a demand for artisans to provide the craft necessary to reconstruct the details of the past. As the author noted, ‘In 1871 the emperor issued an order for the construction of the Imperial-Royal Museum for Art and Industry on the Stubenring together with an adjoining school, the first museum of arts and crafts to be built in continental Europe.” In his book, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna, Donald J. Olsen aptly described the Ringstrasse as an example of what he called, “representational” architecture.” The author defined such architecture as a building or buildings that “did not merely depict a hierarchical social structure but provided a stage on which the kind of life appropriate for those at the top of the hierarchy could be most conspicuously be pursued. The key word is conspicuously, for the representative life-style stood opposed to the pursuit of privacy and domesticity.” Indeed, the Ringstraße, as Loos pointed out functioned like a stage-set of social stability, a façade which hid the truth of social and political change roiling beneath the surface. What was presented on the “stage” of the city of Vienna was the newly wealthy and powerful middle class. This was not necessarily a class that would challenge the status quo, hence the historicized and supposedly stabilizing style of the Ringstrasse that advertised the coherence and continuance of the Empire. As Olsen wrote,

All of Vienna lay within the immediate sphere of influence of the court. Courtly display served as a model and idea not merely for the nobility in their town and suburban palaces, but for the greater bourgeoisie imitate with assiduity the manners of the court nobility. The stress on the impressive entrance to the Ringstrasse block, the grand public hall and staircase, and–within the flat–the emphasis on reception rooms at the expense of kitchen, bedroom,and accommodation for the family reflected the extension into private bourgeois life of the values and priorities of absolutism. The Ringstrasse successfully conveyed the idea that it was occupied by individuals and institutions of more than ordinary importance, that what went on behind the massive and highly and ornamented walls had to be taken very seriously indeed. Even those areas devoted to pleasure–the opera, the theaters, the cafés and restaurants and parks–ere not to be approached in a mood of thoughtless frivolity. The architecture, heavy, solid, and uniform, evokes emotions of awe, wonder and feat more readily than affection and delight.

Olsen continued, “It was not so much the historical nature of the architecture–all architecture of the period was historical–as the particular historical references and reminiscences of the monuments and buildings that render suspect the interpretations that they express specifically bourgeois values. Ritual, hierarchy, leisure, extravagance, all expressed in a style closely associated with eighteenth century absolutism, are not virtues one would have expected a bourgeoisie truly confident in itself to espouse..” From the perspective of Viennese artists of the avant-garde persuasion, the Ringstraße was a huge and tempting target. In an increasingly modern era and in a new century, the nineteenth century concoction seemed increasingly irrelevant and dated beyond aesthetic endurance. Backward and naïve in conception, the flaunting of a kind of capitalism that yearned for association with an anachronistic, decadent and corrupt nobility, was an architectural obscenity that had to be addressed. Preaching utilitarianism and purity respectively, conservative architect Otto Wagner (1841-1918) and the newcomer Adolf Loos (1870-1933) would lead the architectural charge towards modernity.