War and Glory

From Meissonier to Detaille, Part One

Born during the revolutionary year of 1848, Jean-Baptiste Édouard Detaille (1848-1912) did not live to see the fate of the French army during the Great War. Riding the nostalgic wave of the cult of Napoléon, which dated back to the reign of the First Emperor himself, Detaille was the foremost military artist of his era. His devotion to the French army and his involvement in its affairs was so great that he attempted to redesign the array of uniforms, making them suitable for the twentieth century. For an entire century, France had been under the spell of Napoléon Bonaparte (1769-1821), and regardless, of whether one thought that he had been good to the nation–he brought glory to the land–or a disaster for the county–he allowed the defeat of a once-great empire, leaving England free to create an international empire and encouraging Prussia into further aggressions, his shadow loomed over the next hundred years. Defying the various regimes that replaced the First Empire, for decades, the cult of the first Emperor was supported by the survivors of the Grande Armée, for whom serving under the general was the formative experience of their lives. When the army, the first army of conscripts was disbanded and the former soldiers were dispersed into the fabric of society, millions of men sought to make sense of the rest of their lives by validating the first part of their existence. They fought therefore they were.

In the minds and hearts of the old soldiers the flame of memory of the Emperor was kept burning as mediocre king after king was tried and discarded. It was not until the nephew of the Emperor, Louis Napoléon Bonaparte (1808-1873) returned from his English exile in 1848 did the cult of Napoléon break into full public view. In fact, it can be stated with some certainty that the prevailing nostalgia for Napoléon, the decisive leader, was responsible for the rise of the nephew who emulated his uncle and elevated himself from being a mere President to an Emperor. The Second Empire under Emperor Napoléon III began in 1852. Suddenly, after years of reactionary academic art and conservative genre paintings, a new market opened up in the art world, the long suppressed desire to celebrate a leader who had brought the nation la gloire could be expressed through a new generation of military painters. As the new Emperor stepped into his uncle’s shoes, he was expected to take on the Napoléonic attributes, such as reestablishing the power of France through military ventures. Sadly, beyond writing pamphlets, Napoléon III had no military background and his attempts be the leader of the French Army in the manner of his uncle was ultimately came to a sad end.

In the beginning Napoléon III promised that he would be a ruler for peace, not war, stating, “L’Empire, c’est la paix,” but he quickly broke his promise and France was soon embroiled in one military misadventure after another. The first war, begun almost immediately after the new Empire began was the ill-fated Crimean War, a war almost entirely without glory for the French. The war was essentially a venture on the part of Russia, testing the idea that the Ottoman Empire was an old and ailing man and taking the opportunity to seize the strategic Dardanelles. England and France, wary of a strong Russia, sided with the Turks in a war where cholera won and many soldiers died. Given that the Russians had outwitted and then decisively routed Napoléon I in 1812, the new Emperor was eager to participate and enact revenge upon the Czar. The French role, compared to the British, was more modest, lacking the crazed inspiration of the Charge of the Light Brigade and other British exploits. But the mere promise of the restoration of France’s military honor inspired artists, such as, Isidore Pils (1813-1875). Pils dazzled the French art audience with a long and large painting based on the Battle of Alma on September 20, 1854. The painting was far more dazzling than the French participation in the battle, which was meager resulted in no exciting tales to tell. In fact the most interesting aspect of the Battle was the use of rifled muskets by the British and the French, an innovation for the infantry which would have profound repercussions for wars of the future.

Isidore Pils. The Landing of the Allied Troops in Crimea (1859)

Although it is unclear if the painter had actually spent time in Crimea with the troops, as an artist Pils was not interested in technological advances in warfare, instead he followed in the time-honored footsteps of established military painting, showing the colorful action of warfare. Pils and Horace Vernet (1789–1863), the premier military artist of the new Napoléonic era, were given commissions to portray and enlarge upon the rather brief participation of Prince “Plon-Plon,” Prince Napoléon Joseph Charles Bonaparte, nephew of the Emperor, at the Battle of Alma. The German art historian, Richard Muther in his second volume of The History of Modern Painting (1897), took a dim view of both artists: “Devoid of any sense of the tragedy of war, which Gros possessed in such a high degree, Vernet treated battles like performances at the circus. His pictures have movement without passion, and magnitude without greatness..The bourgeois felt happy when he looked at Vernet’s pictures..” Muther made a perceptive on the problem faced by military artists in a period of modern war: “The soldier of the nineteenth century is no longer a warrior, but the unit in a multitude; he does what he is ordered, and for that he has no need of the spirit of an ancient hero; he kills or is killed, without seeing his enemy or being seen himself. The course of a battle advances, move by move, according to mathematical calculation. It is therefore false to represent soldiers in heroic attitudes, or even to suggest deeds of heroism on the part of those in command.” The art historian went on to condemn the uninspired works of Adolphe Yvon and Pils, stating, “The fame of Isidor Pils, who immortalised the disembarkation of the French troops in the Crimea, the battle of Alma, and the reception of Arab chiefs by Napoleon III, has paled with equal rapidity. He could paint soldiers, but not battles, and, like Yvon, he was too precise in the composition of his works.”

The British author of the review of art exhibitions in Paris in the 1867 issue of the Contemporary Review was a bit kinder to the French military artists, writing jauntily, “Assuredly no nation can beat the French in the painting of a battle: since the days of Horace Vernet, battle pieces have become specialities in Paris..Our lively enterprising neighbors are just the fellows for a skirmish either in the field or on canvas: the Zouave enters the studio; the artist slashes and dashes with his brush as with sword or bayonet. No sooner is a campaign planned, or battle fought, than painters are ready to commemorate the victory. An artist is as indispensable to the grand army as a drummer or a chaplain. The last war is always the favorite theme in a French picture gallery..and now the Chrimean furnishes the present Exhibition with two enormous pictures expressly in the Vernet manner..It is surprising what movement, energy and passion animate these desperate onslaughts. Clever they are unquestionably; realistic to a marvel; vivid as the scenes themselves; vigorous as paint can possibly be made when loaded thick as plaster. These tours de force, however, cannot be too strongly reprobated for their inhumanity and barbarity: it is difficult to understand how men can have the heart thus to depict in al the horrors of blood the buttery of the battle-field. The French talk of the glory of war, and certainly their painters glutted in its carnage.”

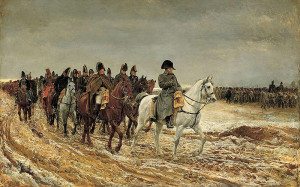

Inspired by the success of the Second Empire, the career of Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), deviated immediately from that of painter of tiny genre scenes to painter of tiny paintings glorifying Napoléon Première and his fame soared from 1860 on. Described by his contemporaries as a short and burly man with a mean disposition, Meissonier was already famous when he shifted his career into the suddenly lucrative area of Napoléonic military paintings. He was a self-proclaimed perfectionist who worked slowly and exactly in what had become a famously precise style of realism. Meissonier researched his military paintings as meticulously as he painted them and his proposed sequence of four paintings of the career of the first Emperor took years of labor and was never completed. The process of painting his important interpretation of Napoléon, encircled by enemies, fighting for his life and on the run between Soissons and Laon was an exhaustive one. Meissonier interviewed surviving soldiers of the Grande Armée and even the emperor’s valet, and then built a wax maquette of the entire scene, complete with fake snow, made numerous sketches before he even began painting. The artist borrowed the coat worn by Napoléon, preserved at the Musée des Souverains and commissioned a copy by a tailor as exacting as Meissonier himself. Meissonier then donned the coat, sat on a saddle placed on a wooden horse and studied how the coat fell. He even wore the coat during a snowfall to study the pattern of snowflakes and quickly copied the color of his cold-reddened face. The dull and gray color scheme set the emotional tone for a doomed campaign, a last ditch effort on the part of the Emperor to save himself.

This difficult period after the defeat in Russia was covered in great detail by the French journalist and historian, Jean Charles Dominique de Lacretelle (1766 – 1855) in 1855 in his book, Napoleon: His Army and His Generals: Their Unexampled Military Career, a nostalgic tome of the Napoléonic Cult. This particular campaign, with Napoléon pitted against the English, the Russians, the Austrians and the Prussians, was an odd choice on the part of Meissonier. According to Lacretelle, the allies were not fighting France but Napoléon himself, dismantling his European empire and offering to leave the Emperor on his throne if only he would confine his activities to France itself. In deciding to fight to retain his throne on his own terms, Napoléon decided to allow the allies to bring war to the soil of France and put his army once again in danger for purely personal reasons. Lacretelle wrote, “It did not suit his high-soaring ambition to be content with such a degree of power as was to be obtained by negotiation..Yet let us do justice to the memory of a man so distinguished. If a merited confidence in the zeal and bravery of his troops, or inches own transcendent abilities as a general, could justify him in committing a great political error, in neglecting the opportunity of secreting peace on honorable terms, the events of the strangely varied campaign of 1814, show sufficiently the ample ground there was for his entertaining such an assurance.”

Ernest Meissonier. Campaign of France, 1814 (1864)

It is not known if Meissonier read this book which details the melancholy Campaign, but the painting illustrates the fact that it is the end game for the Emperor and the viewer is overwhelmed with the feeling of defeat and futility of a wounded ruler in an empty and blank landscape, predicting his future. The painting was an odd beginning in what was a proposed series of five works on the career of the first Emperor. Meissonier would never complete his project, but he would mentor two young military artists, Édouard Detaille and Alfred de Neuville, who would carry on his work in difficult times. The next post will discuss the end of Meissonier’s career and the end of nineteenth century military painting.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.