War and Glory

Lady Elizabeth Butler

Since the dawn of time, war has been one of the favorite topics for artists. From the Egyptians to the Assyrians, war has been depicted as glorious and victorious, with the rulers smiting enemies and slaying any army foolish enough to resist. Although from time to time, certain artists, such as Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835), allowed a glimpse of realism to intrude around the edges, but, by the nineteenth century, the overall picture of war was one of glorious entertainment. The audiences for military paintings had grown to the point that there was a separate genre for paintings of battles and campaigns, all brightly painted with shiny weapons and colorful uniforms, full of dramatic action. The growing taste for paintings of war corresponded with the rise of empires in the nineteenth century and fed the identity of nations, so necessary to international politics of the period. Specific countries, such as Germany and Italy that had never existed as untied entities until the end of the nineteenth century, emerged to challenge the older orders of England and France and Russia and Belgium. Supposedly unique characteristics of a people became politically significant and militarily important and these traits, supposedly “Germanic” or “English” were thought of in terms of “race,” or allegedly intrinsic or inherited cultural elements handed down for centuries. Military paintings portrayed these racial characteristics and celebrated victories and battles that expressed nationalism and pride in one’s country. As such paintings of war reiterated the diplomatic struggles for empire and dominance playing out internationally during the end of the nineteenth century. Perhaps because military paintings were linked so closely to a nation’s heritage and history, they tended to be conservative and traditional, untouched by the avant-garde controversies of the fin-de-siécle.

In art history military painting in the late nineteenth century has been passed over in favor of studying vanguard art, but in its quaint backwardness, these works of art presented a very real challenge to the artists of the early twentieth century. And even more importantly, the paintings with all their fictional heroism reflected a mindset that was very real and this idée fixe was likely to play out on the field, during actual combat. The visual idea of war, established with such striking drama during the Napoléonic period, became part of a belief system that the best way to fight a war, indeed the only way to fight a war, was with the tactics used by Napoléon and Wellington on the fields of Waterloo, where the (well-dressed) winners and losers confronted one another across an empty field, brightly colored line marching towards vividly hued line. The tangled nineteenth century ideal of victorious warfare and its visual celebrations met up with the twentieth century in August of 1914. Suddenly old ideas of what war should be collided with the reality of what war had actually become and artists faced the problem of how to express a war bereft of glory and defined by death. In order to understand the problem of creating a new visual language for a new war, it is necessary to examine the old language–the existing vocabulary as practiced by the leading artists of their time–in order to recognize the formidable challenges modern warfare presented to modern artists.

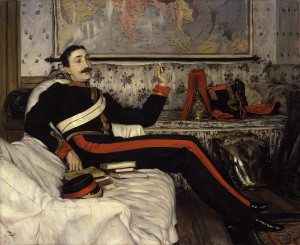

However, late nineteenth century military artists had their own problems: since the Napoléonic wars early in the century, there were very few glorious battles to illustrate. For the French, the defeat of Napoléon at Waterloo in 1815 was the end of gloire and the beginning of years of inglorious ambiguous campaigns. For the English, the end of Napoléon was indeed glorious but, like the French, the subsequent wars were unpopular and unsuccessful. In both England and France, the artists looked back nostalgically to the age of clear cut winners and losers and a field where honor supposedly reigned and upon which death could be a meaningful sacrifice. However, the wars of their own time, presented very real problems. Thanks to modern modes of communication and reportage from the actual battlefields, the public was no longer dependent upon official military and governmental dispatches and was aware of the true cost of war. This information, readily available in any newspaper, had to acknowledged and taken into account, even in defeat, but the honor of the nation an its fighting men had to also be honored. Serving in the military was an excellent job for the lower class male, being fed and clothed by the government, employed and then pensioned after serving for twenty one years. For the upper and middle classes, the army or navy was an excellent place for younger sons who would inherit little or nothing from the family estate or for young men disinclined towards other middle class vocations. In the British class system, men of these ranks were automatically trained as officers, regardless of their competence, a practice that would prove disastrous during the Great War. The splendid uniforms worn by these officers were recruiting tools in an of themselves, and was brilliantly illustrated by the wonderful portrait of a very elegant British officer, Colonel Frederick Gustavus Burnaby (1842-1885), painted with loving care by the Anglo-French James Tissot (1836-1902) in his “at ease” uniform. A private painting owned by Burnaby’s privileged family, this portrait, which was not publicly exhibited until the 1930s, exudes the confident imperialism of its time and the sense of British superiority that fueled the Empire.

Portrait of Burnaby in his Uniform as a Captain in the Royal Horse Guards (1870)

Interestingly, the portrait, painted just before the most disastrous war France ever fought, the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, is of a legendary adventurer and imperialist whose military career was unfortunately situated after wars worthy of his uniform. He spent a great deal of his career, traveling on adventures of his own, as he chased wars and glory all over the globe, authoring books on his journeys, The Ride to Khiva (1876) and On Horseback through Asia Minor (1877). He alleviated the boredom of his retirement by initiating the first crossing of the English Channel in a hot air balloon. Burnaby followed up his daring ride by attaching himself as a private citizen with experience to British imperialist venues in Africa, where he died in Khartoum from a spear thrust. Burnaby’s career was indicative of kinds of military actions in the British Empire, skirmishes in distant parts of the world, where the “natives” did not fight European style and where glory in the service to what was essentially a financial enterprise was hard to find. The very real difficulties of finding suitable military topics make the successful career of one of the most celebrated military artist, Lady Elizabeth Butler (1846-1933), is an interesting case in point.

Elizabeth Thompson, later Lady Butler. Roll Call (Calling the Roll) (1874)

Butler first achieved fame and recognition under her “maiden name,” Elizabeth Thompson for her thoughtful painting of the Crimean War, Roll Call (Calling the Roll). Twenty years after this unpopular war exposed massive incompetence within the British Army, thanks to the tireless reporting of William Howard Russell (1820-1907), the first war correspondent for the Times of London. Starting in 1853, the war ended anti-climactically, with the British, French, Turks, and Sardinians winning against Russia, while the bone of contention, the Crimean Peninsula, remained under the power of the Czar. In popular memory, the war was best remembered for its causalities and high death toll, though disease and the failures of upper class leadership, thanks to Russell who stated, “Lord Raglan is utterly incompetent to lead an army.” Indeed, this war, during which the fighting lasted one year, 1854-1855, was distinguished for having the highest casualty rate of any war between 1815 and 1914, a century. Before the Thompson’s painting, the tragedy of this war had been best expressed in the poet by Alfred, Lord Tennyson (1809–1892), The Charge of the Light Brigade (1854), marking a totally futile attack by a mounted calvary unit in the face of Russian cannons. The second stanza summed up the bravery of the troops and the stupidity of the commanders, reported upon eloquently by Russell, and, although the Poet Laureate could not have known this, predicted the slaughters of the Great War.

This is the context for Roll Call (1874), painted twenty years after the Crimean War itself, but the memories, even in a time of imperial glory, of this ill-begotten war, were strong. She said, “I never painted for the glory of war, but to portray its pathos and heroism,” and it was her empathetic approach to the ordinary soldier that won her attention. The young woman wrote, in an amazed tone, to her father, “You know that the elite have been presented to me this day, all with the same hearty words of congratulation on their lips and the same warm shake of the hand ready to follow with a the introductory bow.” Roll Call so impressed Queen Victoria that she pushed away all the would be buyers and purchased it herself. The novel approach of the work of art was rested on its homage to the bravery of the troops who bore the burden of the Empire shown regrouping after a futile battle. The pathos, as Butler expressed it, was a startling contrast to the tradition of glorifying conflict. Perhaps only a woman, the daughter of wealth and leisure, gifted with talent and opportunity, had the power and position to provide a portrait of soldiering and a veiled criticism, softened by the name and presence of a woman. Like the hero, nurse Florence Nightingale, who liked her paintings, Butler, who was called “The Florence Nightingale of the Brush,” “cared for” the anonymous soldier who served so bravely. During the annual exhibition for the Royal Academy, crowds stood transfixed, gazing at the moving painting and, perhaps, remembering those who did not come home.

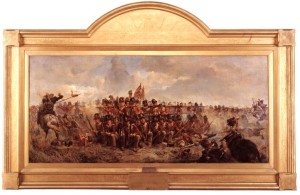

Elizabeth Thompson. The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras (1875)

More honors were to come. After her success at the Royal Academy in 1874, Thompson followed with a rousing and stirring scene of heroism, The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras (1875). Although most of her paintings followed the humanizing theme of Roll Call, Butler, who later married a military man and traveled with him, she was quite capable to creating moments of glory. In Quatre Bras, she excelled herself and attracted the attention of the foremost critic of Victorian England, John Ruskin (1819-1900), who had always maintained that women could not paint. According to the Victorian Web, Thompson recreated a historical event that took place just prior to the decisive battle at Waterloo, taken from Captain William Siborne’s History of the War in France and Belgium in 1815..“ Thompson chose the moment at about 5 o’clock in the afternoon when the gallant 28th braced itself for one massive, final charge of terrifying Polish Lancers and cuirassier veterans led by Marshal Ney.” Like her French counterpart, Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), Thompson prized accuracy, finding a rye field, like the one where the battle was fought, having the correct uniform remade for the models. Her efforts rewarded, not just by the attentions of the admiring crowd, but by a favorable review by Ruskin,

I never approached a picture with more iniquitous prejudice against it, than I did Miss Thompson’s; partly because I have always said that no woman could paint; and secondly because 1 thought what the public made such a fuss about, must be good for nothing. But it is Amazon’s work, this; no doubt of it, and the first fine Pre-Raphaelite picture of battle we have had; — profoundly interesting; and showing all manner of illustrative and realistic faculty. Of course, all that need be said of it, on this side, must have been said twenty times over in the journals; and it remains only for me to make my tardy genuflection, on the trampled corn, before this Pallas of Pall Mall.

When Thompson showed Balaclava in 1876, featuring the return of stunned and wounded British soldiers, staggering to safety. It is this painting that inspired Tennyson to invite the artist for a visit. Thompson brought her sister, the poet Alice who would become famous as Alice Maynell to the meeting. Her fame continued with The Return from Inkermann (1876-7), but marriage and six children and a life of constant travel as the wife of Irish Major William Butler interrupted her career as an artist. Meanwhile the art world in London had moved past her brand of late “Pre-Raphaelitism” Butler was credited with, and in 1881, the artist found herself in the prominently avant-garde Grosvenor Gallery, staunch supporter of James Whistler, strolling through an exhibition of “the ‘Aesthetes’ of the period, whose sometimes unwholesome productions,” as she up it, annoyed her. In “exasperation was I impelled that I fairly fled and, breathing the honest air of Bond Street, took a hansom to my studio. There I pinned a 7-foot sheet of brown paper on an old canvas and, with a piece of charcoal and a piece of white chalk, flung the charge of ‘The Greys’ upon it,” she reported. The result was her last famous and celebrated military painting, Scotland Forever! (1881).

Lady Elizabeth Butler. Scotland Forever! (1881)

The mood of this painting was quite different from the earlier and more thoughtful version of war. Based on the calvary charge of the Royal Scots Greys at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Arguably, this charge and the others during the Battle were among the last of their kind. When the British Calvary charged the Russian cannons in 1855, military technology had changed and running heedlessly towards artillery meant one thing–not glory but instant death. In fact, the fate of the Royal Scots Greys was ambivalent–heroic but tragic. The Greys had been held back in reserve during the Battle until the regiment’s commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel James Inglis Hamilton, decided to move forward, without orders, in support of the faltering 92nd Highlanders. The dramatic forward charge depicted by Butler did not take place. The field was too churned up and too full of bodies and for the safety of the horses, it was necessary to pick a careful path to the French lines at a cautious walk. According to Military History, Sergeant Charles Ewart caught sight of the French imperial eagle of the 45e Rgiment de Ligne, the battle standard and most prized possession of any French regiment” and he rode forward and captured the flag. After that moment of glory, the British troops and their horses were disorganized and exhausted and they were attacked by Baron Jaquinot’s 1st Cavalry Division. In the end the charge had won a French eagle but the retreat had cost 104 men dead, 97 wounded as well and 228 horses perished. All this dying for a banner.

Elizabeth Thompson Butler was among the best military artists of her time and her work exemplified how paintings of war could be done in a period when conflicts were becoming modernized and mechanized. Despite her upper class upbringing, which, incidentally had no military connections, all Butler wanted to paint was war. Scotland Forever! was an oddly triumphal work in her oeuvre which was mostly human interest stories and genre scenes. What is significant for the future of military painting in the twentieth century is Butler’s adherence to nineteenth century realism as her mode of depiction. Her style was, in a sense, timeless, always readable. Butler, as she stated, had no patience with modern avant-garde art. For her the academic style was best suited for military paintings, because if for no other reason, the Academy supported the goals of the state and the Empire. Her paintings always tell a story, not necessarily of glory, but at least of British history. Butler’s works, displayed at the Royal Academy during the rise of imperialism, were shown to admiring audiences at a time when the British Empire, backed by military might, was reaching its peak. Support of the military was patriotic and Butler’s sotto voce criticism of needless sacrifice of brave soldiers was accepted, just as the deaths of nearly two hundred men were considered a fair price for a French eagle, a symbolic flag.

In writing of Lady Butler and her role in depicting the ideals of the British Empire, Krzysztof Z. Cieszkowski, stated that long after her days of fame, “..her images of Imperial glory remained popular long afterwards, in the form of coloured prints on classroom walls and illustrations in school history-books. Her paintings, once regarded as true and valid images of the events they portrayed, are now eloquent of how the age saw itself – the imagery that fed an insatiable popular appetite for national glory, and which helped provide the popular support for the imperial adventures of the military heroes of the Victorian age.”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.