Master’s Houses

Walter Gropius, Junkerswerke, and Modern Architecture

Today the architecture of Walter Gropius (1883-1969) and his series of Bauhaus designed domestic dwellings for the Masters, the “Meisterhäuser,” at the art school are considered jewels in the crown of the modern built environment. But for the majority of their lives, these homes and the Bauhaus building itself existed in hostile territory. Less than ten years after the distinctive houses were completed in 1926, the Nazis closed the Dessau Bauhaus in 1932. The Nazis disapproved of modernism in the arts and favored a heavy-handed faux Neoclassicism in architecture, thus the white cubes of the seven pioneering buildings did not please the sensibilities of the followers of Hitler. The city of Dessau, now the owner of the famous Bauhaus building and the cluster of faculty housing, all designed by Gropius, rented the homes until 1939 when the Second World War began. But turning the masters’ unique modern white cubes over to unsympathetic tenants was not the end of the travails suffered by the concrete structures. The city subsequently sold the houses to the Junkers Works, a more careful and concerned owner, which had had a long and mutually satisfying union with the school. It was a former student, Marcel Breuer, who probably sought out Junkerswerke, which crafted metal shapes in steel. Inspired by curved bicycle handlebars, Breuer wanted to bend the base of his new chair from metal, foregoing straight wooden legs. If the proper industrial process could be created, his chair could cantilever and balance itself. In 1925 Breuer worked in the factory, tutored by Karl Körner, a locksmith, who taught him the craft of metalworking. His tubular steel chair, the Cassily, could be produced only by special bending machines, available at Junkers, and was the first of his many furniture designs utilizing curved metal.

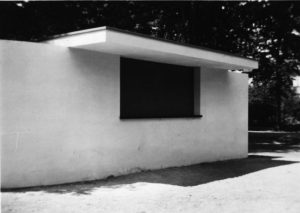

By 1926, as a result of the partnership forged between Junkers and the Bauhaus, the school and the industrial manufacturer began a number of projects together, including a set of homes for the Bauhaus Masters. As part of his goal of fusing art with industry through modern design, Gropius arranged for the factory to install a series of what were termed new “thermotechnical” units in the new homes in order to model modern housing and modern living in an “organic” symbiosis. According to the Junkers factory website, the internal luxury items included wall ventilators, “gas appliances such as hot water flow-type calorifiers, gas stoves and gas ovens.” Such experimental conveniences, after the years of deprivation during the Great War, were from the future. The Bauhaus Masters’ Houses were, therefore, test houses, maintained by Junkers technicians, who not only made sure the modern equipment was functioning properly but also tested for technological performance. The association between Junkers and the Bauhaus extended to a rather odd building called the Pump Room or “house.” In Germany, a “pump house” or Trinkhalle is a refreshment stand, and as part of the general modernization of Dessau, a number of these stands were planned and constructed throughout the city. The Pump House with a Bauhaus connection was a modification of the wall built by Walter Gropius around his own residence. Although the austere white wall afforded the Gropius couple privacy, it also had the effect of blocking the view to an eighteenth-century estate built by the princes of Saxony with a Georgium, an English-style landscape garden, complete with fake Roman ruins. This cluster of elegant buildings, a guest house (Fremdenhaus), an Iconic temple (Monopteros) and the Flower House (Blumengartenhaus), all set in the lovely garden, were a strong contrast the white blocks designed by Gropius. His successor at the Bauhaus, Mies van der Rohe solved the problem of the blank white wall by inserting a window into the side on the corner of Ziebigker Strasse and Ebertallee, floating a roof over the opening for shading. By the simple means of breaking through the wall, a conceptual line of sight to the historical gartenriech was restored. Shortly after the Pump House was completed, the Nazis took over and the Bauhaus houses were sold to the Junkerswerke. Sadly, the only building in Dessau designed by Mies was demolished in 1970.

Mies van der Rohe. The Pump House (1932)

Junkers, headed by Dr. Hugo Junkers (1859-1935), was an aircraft and engineering works, specializing in the manufacture of steel and airplanes, thus immediately came under the control of the Nazis, who considered the staff to be full of communists and Jews. Junkers himself was arrested was exiled. He died in 1935, never knowing that his aircraft, bearing his name, would bomb Guernica two years later. According to the article, “Bauhaus, Brown Coal and Iron Giants,” Peter Marcuse, by 1932, the faculty and students had been driven from the Bauhaus in Dessau and retreated to their last stand in Berlin. Meanwhile, the Bauhaus building was turned into a girls’ school, where young women could study Kinder, Kirche und Küche, and then men moved in and the facility was transformed into a training center for Nazi officials. The school also provided offices and work space for Junkers personnel and their drafting operations. Even Albert Speer had a construction office on the premises. During the Second World War, Dessau lost three-fifths of its buildings to allied bombing and the masterwork of Gropius himself, the Bauhaus building, was badly damaged on March 7, 1945, right at the end of the War. As the headquarters for an important aircraft manufacturer, Junkers, the town was naturally targeted and almost was almost completely destroyed. In its ruined state, the site and what was left of the building was used as a camp, first for prisoners of war and then for refugees. After the War, ownership of eastern Germany and the town of Dessau was transferred to the Soviets, another regime that disliked anything European and avant-garde.

The Original Bauhaus on its opening day, December 4, 1926

But the communist regime showed more respect for the idea of the Bauhaus than the Nazis who had their own artistic agenda. Immediately after the War, the Bauhaus archives were transferred to Berlin and a new building was commissioned to house the materials. The architect was none other than Walter Gropius. During 1946 to 1948, there were attempts to restore the building. However, unlike West Germany, East Germany did not have the resources to rebuild and it was not until 1961 that another restoration took place, followed by another phase in 1965. In 1974 the building became an official cultural monument, inspiring a yet another restoration in 1976. After the Wall came down, Germany was reunited, and the Bauhaus underwent its final and definitive restoration, a ten-year project, completed in 2002. The Masters’ Houses, being ancillary to the main building, did not have the iconic status of the school, but these houses, in their own way, were unique experiments in living. Collaborating with Junkers, Gropius was re-thinking what the modern home should be like and how modern people should inhabit it. He mused that “the organism of a house evolves from the course of events that have predated it. in a house it is the functions of living, sleeping, bathing, cooking, eating that inevitably give the whole design of the house its form… the design is not there for its own sake, it arises alone from the nature of the building, from the function it should fulfill.”

The forest-like environment for the Masters’ Houses

When the mayor of Dessau, Fritz Hesse, asked the Bauhaus to take residence in his industrial city, part of his promise was not only land for the school but also a site for faculty housing. The city provided Burgkühnauer Allee, quite close to the school itself, in a wooded and quiet area. In this tiny forest, Gropius designed a large free-standing home for himself and three double houses, paired and attached, for the Masters. The group of homes was built in a year, using mass produced materials, such as concrete blocks. Gropius was experimenting with the idea of prefabricated construction–not yet possible–with the post-war housing shortage in mind. The concept of the “large scale building set” can be best viewed in the masters’ homes, which were equal in size, but each structure was a variation on the basic cube, giving the cluster of modern architecture variation and rhythm, ruled by simplicity. As Gilbert Lupfer and Paul Sigel noted in their 2004 book, Gropius. 1883-1969. The Promoter of New Form, “Thus the Houses for the Bauhaus Masters served as a practical experiment with Gropius’s building block principle (Baukasten im Großen)..The building block principle was meant to allow, depending on the number and the needs of the inhabitants, for the assembly of different ‘machines for living.'” Gropius explained, “All six of these houses are the same but different in the impression they make. Simplification through multiplication means quicker, cheaper building.”

The Director’s Home of Walter Gropius

In the end, there were seven homes in all, but the home of the director had a few added features. As the home of the Director, the Gropius building was large, had a garage and rooms for servants’ quarters, all surrounded by a tall white wall. In the kitchen, there was, compliment of Junkerswerkes, a hot water pressure spray. Such a spray would be a standard feature in any home today, but in 1926, such an item would have been a novelty. The Bauhaus-designed furniture in this home included a sofa that opened up and converted to a bed. Next door to Gropius, László Moholy-Nagy, his right-hand man, lived with his wife, the Bauhaus photographer Lucia Moholy. Lyonel Feininger and his wife and two children occupied the other half of the joined homes. The next duo was occupied by Georg Muche and Oskar Schlemmer and their families. Completing the triumvirate of Masters’ Houses, long time friends and close collaborators, Vassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee abutted one another. The Gropius designed buildings, based upon cubes, were simple, flat-roofed, white faced and marked only by the large black framed windows, touched with markings of bright primary colors. The equality of each duplex was guaranteed by simply rotating the design for the first segment and then building the second half at a ninety-degree angle.

Muche-Schlemmer House with an external restoration that retained internal changes done to the homes by subsequent owners

In northern Europe, large expanses of glass, which, at that time, could not be double-paned, would be quite cold. In the winter, these beautiful homes were uncomfortable and the open rooms needed to be warmed by some form of space heaters. Feininger used a coal stove, while Klee and Kandinsky demanded a refund for their heating bills from the city of Dessau. In the summer, the temperatures swung in the other direction and the sun streamed in through the glazed walls, baking the unfortunate inhabitants. These open spaces were the studios where the artists worked, with all the other rooms arranged around the central ateliers. There were even rooftop terraces where the artist could sunbathe in warm weather. The interiors of each home were different. Only Gropius and Moholy-Nagy used Bauhaus designed exclusively, and other Masters brought their own furniture with them. As lovely and as advanced in avant-garde modernist design, the Masters’ Houses were hard to maintain and, in their own way, were fragile, requiring constant upkeep. Although the homes were demanding of their residents, the artists, in turn, attempted to impose their will upon these experiments in modern living.

Interior colors

Klee and Kandinsky used their white-walled homes as blank canvases for the color experiments, painting their interior spaces in almost two hundred colors, an abandonment of the austerity preferred by Gropius that came to light only upon restoration. All of the homes used built-in closets, wardrobes, and cabinets, eliminating the need for all but the most basic furniture. Nevertheless, the Kandinsky home mixed the famous “Vassily chairs” with their own old-fashioned Russian furnishings. For all their exterior simplicity, the luxury of these houses was quite at odds with the Marxist sympathies of the inhabitants. Nevertheless, the original faculty and those who followed them, enjoyed living in these novel experiments in domestic living, but the coming of the Nazis and then the Second World War scattered the Masters, who would never return.

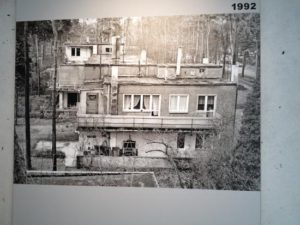

A photograph of the modified Masters’ Houses before restoration

The now hostile city of Dessau, hewing the Nazi line, instructed the new owner, Junkerswerke, to eradicate the “alien” architectural style from the structures, stating that “the outer form of these houses should now be changed so that the alien building forms are removed from the town’s appearance.” There is little indication that the leaders of the industry were interested in altering the homes, after all, Junkers himself was banished by the Nazis and the corporation had better things to concern themselves with. However, the occupants themselves organically altered the houses to suit their more middle class needs and bourgeois expectations. They bricked up the huge and drafty windows, threw up partition walls to enclose the open spaces, added chimneys, and, over time, the original cubes were swallowed up by modifications. And then came the bombings. The Gropius home was completely destroyed down to its foundation and the Moholy-Nagy section of the duplex next door was severely damaged and torn down. For years, no one was concerned about the lost work of a distinguished architect, and what was left of the complex was rented out and allowed to deteriorate. The Feininger home became a doctor’s office. Finally, after the Fall of the Wall, the architectural importance of the Masters’ Houses was recognized and restoration began in the early 1990s.

The Klee-Kandinsky Houses

As indicated by the cautious restorations of the Masters’ Houses, recovering the iconic exteriors while retaining interior modifications, the role of history and the meaning of the lost “original” becomes an exchange. The Bauhaus building and the homes of the Masters, as we see them now, are not the original buildings; they are replicas. Philosophical questions arise when considering how to respect the entire history of a building: does one restore/rebuild a replica or does one respect a past, no matter how checkered, and allow historical alterations to remain? The questions are really ones of authenticity versus honoring the original intent of the architect, which are actually, in this case, at odds with one another. To solve these genuinely unsolvable problems, the final restorations of the destroyed home for Gropius and the Moholy-Nagy section of the duplex were reconciled as “ghost houses” in 2014. As Connor Walker explains in Arch Daily, “Rather than restore the buildings to their original appearance, the renovation architects reconstructed the meisterhäuser to re-emphasize the spartan qualities that were championed by Bauhaus Modernists. In addition, the windows of both houses were covered in an opaque wash, giving them an ethereal appearance.” Described as “minimalist arrangement of geometric shapes” by Alyn Griffiths in Dezeen, the “ghosts” of the destroyed homes were reinterpreted by Bruno Fioretti Marquez. The result is a novel solution, resulting in a new building that is both material and immaterial, a memory and a reality, an homage and reconstruction, and, above all, a healing of architectural wounds.

Bruno Fioretti Marquez. Ghost of the Walter Gropius House (2914)

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed.

Thank you.