Walter Dorwin Teague (1883-1960)

The Camera in Style

The timing of the Gift Kodak could not have been worse and boded ill for the new partnership of Walter Teague and America’s most famous maker of cameras. Released in November of 1931, the “Gift Kodak” was the perfect Christmas present for the stylish female. But the mechanics of the design were really quite remarkable. Kodak cameras were utilitarian, efficiently put together according to the needs of function. A camera was a dark box, a black room, a useful and unadorned camera obscura with a roll of film inside. One merely removed the lens cap, pointed, “shot” or took the picture; and when the roll of film was finished, the owner simply mailed the camera back to Kodak. Kodak, in its turn, developed the images, replaced the plain black camera with its identical twin and sent everything back so that the cycle could continue. But the beautifully designed “Folding Pocket” model suggested that the camera could be a fashion accessory. The design was old: a lens attached to a flexible bellows that could be pushed back or pulled forward. What was new was that the lens and bellows were attached to a shallow box, which could be thin because, instead of a plate in the back of the camera, the flat and foldable bellows was connected to two ends of film stretched from one spindle to the other. With each click of the camera, the film strip moved forward until all the images had been taken. Compressed, the entire apparatus could be placed in a flat box and presented as a gift. What Teague did next was clever. He used the prevailing art deco taste for lines and stripes and mimicked the notion of a ribbon wrapping around a gift. Instead of ribbon, however, the combination of lines and geometric shapes–circles–was made with cedar wood. What was in fact little more than a holder for film attached to a box became an elegant and upscale gift that unhappily arrived in the market just in time for the Depression.

The idea of the humble Kodak camera as an object of desire had its origins in the Jazz Age, the era of art deco. Art Deco was essentially a French style and had been introduced to the public only in 1925 but three years later, in 1928 Walter Teague was commissioned by Kodak to redesign its very plain black boxes or cameras. Teague immediately applied this very new and very sophisticated decor, based on Cubism, to a plain utilitarian machine. In 1930 he delivered the “Beau Brownie,” a stylish update of the unadorned original. The Beau, still a tall box with a lens, was adorned with a leather-like covering with an interlocking design that spiraled out from the circle of the lens and then climbed vertically up and down the front in an art deco geometric cloisonne grid. The faceplate lines were made with polished nickel and the inlaid colors. a somber black accented with a dark maroon, a steely navy blue paired with an aqua, dark turquoise punched up by a pea green, soft rose central shape surrounded by a coordinating orange-red, and a bronze-toned brown with an ochre accent. The owner could take eight pictures with these stylish cameras, called the No. 2 and No. 2 A models. The Depression brought an end to the entire line of cameras and ceased to be made in 1933.

The box camera had a cousin, the vest pocket camera which, thanks to the flexible bellows, folded into a flat rectangle, which could be placed in a pocket. Women had been encouraged to become photographers, but only as an amateur, and nothing said “unprofessional” like the “Vanity Kodak” made, naturally, for women. These cameras, sold between 1928 and 1930, came in a number of colors, charmingly named: Bluebird (deep blue), Cockatoo (green), Sea Gull (gray), Redbreast (red), and Jenny Wren (brown). To complete the “outfit,” the bellows wore, so to speak, matching colors. Sadly, the fabrics for the bellows were too fragile for frequent use and they were replaced with a sturdy black accordion. The name “vanity” came from the idea that a camera could also be a sort of purse, with a holder for a lipstick, a built-in change purse, a compact where one could place a circle of pressed powder, and a mirror. These were expensive cameras. In contrast to the handsome gift Kodak, which was packaged in a cardboard box with matching design and cost about $16, the Vanity ensemble was $30, expensive for the era. The advertising campaign quoted on the Kodak website makes it clear that the customer base had to be well-to-do: “Newest of the Smart Gifts…for the Girl Graduate, the Bride, the Bridesmaid, the Birthday…distinguished, dainty, feminine…Bryn Mawr, Wellesley, Vassar, Smith ’28 join Park Avenue debutantes in acclaiming these gloriously colorful Kodaks the loveliest gift creations seen in years. Swagger…aristocratic…modernity at its best…those are words to describe what is probably the most momentous addition of the season to the correct ensemble.” The coded language spoke to the upper-class female who was an aristocrat who attended the Ivy finishing schools and lived on Park Avenue, carrying on her life in a “correct” way, apparently meaning never being without make-up.

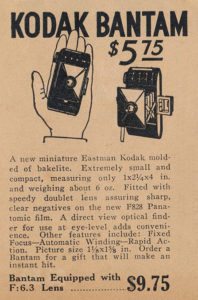

The Depression brought an end to the entire line of cameras and ceased to be made in 1933, but the 1A Gift set, if complete with box, is worth over $7000 today. However, the lean years did not mean that Teague stopped designing interesting cameras for Kodak, but the cameras did become more serious and darker. A case in point is the Bantam Special of 1936. Deep into the sixth year of the Depression, Teague presented the nation with a somber black Bakelite camera. Not a plain box with Art Deco embellishments but an oblong enamel box with horizontal aluminum stripes, the body of the camera revealed in rows. This camera is not–unlike the box cameras and the bellows of the early thirties–a relic from the early days of the Kodak camera collection. The Bantam f.8 was a brand new streamlined model that could be held comfortably in the hand, placed easily in a pocket, and then unfolded upon demand when a handle on the left side was pushed. Measuring just 3 and 3/16 by 4 and 13/16 inches and flattened to an astounding 1 and 13/16 inches deep, the camera weighed only 17 ounces due to its lightweight aluminum die-cast body. A photographer for Collectors Weekly propped up an example on a small stack of dimes in order to display it to full advantage, but in the process showed how small this camera was compared to dimes, the smallest coin of the realm. An advertisement of the time shows the camera resting in the palm of a hand: a “bantam” indeed.

When one opened the front of the camera, the aluminum hinges along the side, swung open to reveal that the large lens was mounted on a truncated bellows. The paper backed 328 film could be accessed in the back where it was attached on the left side and unrolled towards the right where it was affixed and then spooled as the shutter was clicked. The size of the Bantam rivaled that of the small concealable Ermanox favored by Erich Salomon, the famous stealth reporter who staked the European diplomatic sites during the 1930s.

The Bantam and the Ermanox predicted the famous 35mm cameras used a generation later by vernacular photographers such as Robert Frank. The Bantam–and one is tempted to call it a “Batman” camera with its dark brooding Art Deco style at its most chic–could easily be imagined as a Batman accessory, if he had been an Erich Salomon type, using the Bantam to photograph Gotham City.

In his article on the line of camera Walter Teague designed for Kodak, Allan Weitz noted that the corporation was attempting to make itself recognizable, a brand, as it were, by introducing a number of cameras that were desirable consumer products. Teague, according to Weitz, suggested that the cameras have matching cases, an accessory obviously targeted at the female customers. For the women, some cameras were obviously gifts, such as the Vanity lines, and the Art Deco styled cases cameras with Art Deco face plates were intended for adults. Teague also designed brightly colored box cameras for children who wanted to take pictures of their friends: the Boy Scout, Girl Scout, and Camp Fire Girl models. Other cameras were more utilitarian and limited in their use, such as the cousin to the Bantam, the Bullet. Unlike the more elegant Bantam, the Bullet was solid black with horizontal grooves. Looking down into the pop-up view-finder, one could take eight 1-5/8 x 2-1/2″ pictures outdoors only. Although the flash bulb had been invented almost ten years before the Bullet was introduced in 1936, the Bullet was no Ermanox and could not be used indoors. In 1939, at the edge of another world war, a special model was introduced for (outdoor) use along the midway of the New York World’s Fair during the day.

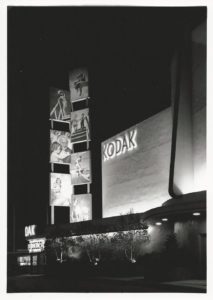

It was this Fair, as will be recalled that Teague designed the cash register for the top of the National Cash Register Building, but that was not his only building for the New York event. He also designed, as would be expected, a Kodak building along with his exhibition structures for E.I. Du Pont de Nemours & Company, U. S Steel, and the Ford Motor Company. Tiffany Webber whose grandfather attended this fair and, with a Bee Bee camera took excellent photos of the Fair’s buildings at night, captured the Kodak building at night.

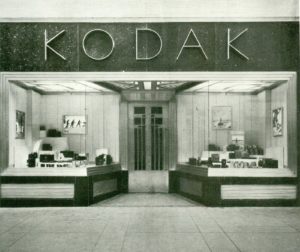

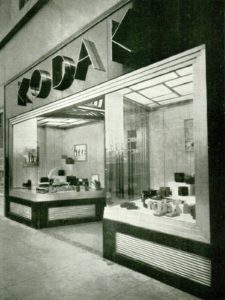

But as interesting as this architecture is with its display of snapshots arrayed like flags along the side of the building, the Kodak store put together by Teague in New York City makes the statement that a camera is a luxury item that is both stylish and affordable. Resembling a jewelry store, the Kodak store used Art Deco as its inspiration for the high style interior. With its glass front situated along Madison Avenue, the Kodak store could not be an ordinary camera establishment and should be understood as a display case for an elegant array of stunningly designed cameras that became works of art in their own right.

A recent article discussing the store stated that its prevailing colors were grey and black and silver colors that appeared in granite or polished and unpolished chrome or benedict nickel or Formica or paint. The soffits on the ceilings were of frosted glass and were arranged in an Art Deco pattern. The doors and inlaid woods of the interiors reiterate the ceiling and its Cubistic geometry. The floors were tri-tone gray and black terrazzo, with blocks laid in an irregular pattern, similar to the walls and ceiling. The store itself was long and the cameras were lined up in glass cases as if they were precious objects for the visitor to gaze upon. Like an Apple store of today, the Kodak store offered the latest in gadgets and the most modern of mechanical objects in the most elegant and thought-out containers. For those who made home movies and who wanted to view their own films in private, there were two quiet projection rooms in the black, treated in rose and silver and chrome.

Today, cameras are digital and are usually located inside a telephone. The iPhone, for example, is designed by Apple engineers and designers led by Jonathan Ive, but cameras, in general, have never had a champion like Walter Teague, who in the name of consumerism, took the humble black box and transformed it into an object worthy of an elegant Art Deco establishment where one came to view the many lives of Kodak.