WILLIAM HENRY FOX TALBOT (1800-1877)

The Pencil of Nature (1836)

THE CALOTYPE

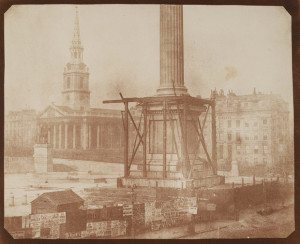

By 1835, William Henry Fox Talbot, an English gentleman, prominent landowner, accomplished mathematician, and amateur experimenter in the photographic arts had produced the world’s first negative, the first half of what would be the basis for the modern “positive”-“negative” process in photography. But Talbot was anything but an entrepreneur and it is clear that from the start, photography was, for Talbot, a mechanical form of sketching and drawing, an art form that he as a country squire would pursue in his leisure time. He was also, typical of his time, part of a large network of amateur scientists who were honored and appreciated in the days in which science could be practiced outside of the cloisters of academia and his work in photography would have been part of experiments with light and thus fitted into a broader context. All of which explains why Talbot saw no need, in the mid-1830s, to either continue his hobby or to make any public announcements on his work. But across the English Channel, a French inventor, named Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre (1787-1851) announced the “invention” of the daguerrotype, a mode of photography, in August of 1839. Talbot, who had invented his own mode of photographing, was galvanized into re-action.

Incidentally, the term “photography,” meaning “writing with light,” had not yet been named. As has been previously noted in previous posts on this site, “photography” in England was developed within the realm of science, as opposed to the shift in France, under the guidance of Daguerre, to the commercial and artistic world. Sir John Herschel (1792-1871), close friend of Talbot, and renowned scientist, began as early as 1830 to determine the defining characteristics of a set of experiments with nitrate of silver and hyposulphite of soda, studies that were still on going. In their article, Proof Positive in Sir John Herschel’s Concept of Photography (2002), Kelly Wilder and Martin Kemp noted that the precise naming of the process/es was tantamount to claiming the invention itself. They write that in 1727, Johann Heinrich Schulz had named the means by which silver salts darkened in sunlight as “scotophorus” and noted that an eighteenth century novel accurately described the photographic process. Despite the naming, the modern history of photography usually begins, not with Thomas Wedgwood, but with Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who invented héliographie in 1827. “Sun pictures” was followed by other names, all of which disturbed Herschel, the premier mind, who determined the proper naming of scientific thought. Scientists actually approached him to properly “name” their work. Herschel wanted names to be empirical and descriptive and part of a system, rather than colorful and poetic and meaningless words, such as “daguerrotype.” Such a name, reflecting the inventor, says nothing about the process and is hence useless.

In March of 1839, Herschel delivered a paper “Note on the Art of Photography of the Application of the Chemical Rays of Light to the Purposes of Pictorial Representation,” months before the 1839 Arago announcement in Paris. Obviously his relationship with Talbot had inspired him to consider photography as a serious candidate for modern naming in a precise manner. But unlike Talbot, as Wilder and Kemp pointed out, Herschel did not consider a photograph a form of drawing but an imprinted fossil or a trace of the real, part of scientific observation, not art, and hence, worthy of his attention. It seems that the scientist understood photography, the sake way as Niépce, as being linked to printmaking. For Herschel, photography was to be an assistance to scientific research and though of photography as a tool for copying nature of empirical information. Photography was evidence, irrefutable proof of truth. Herschel first used the term “photography” in print in English in the winter of 1839 and, due to his considerable importance in the world of science, the name stuck. But thanks to Talbot, photography was first established as an art form, as the “pencil of nature,” through independent photographs, artfully composed images of selected views of Lacock Abbey.

Upon hearing of Daguerre’s work, Talbot immediately wrote to François Arago, noting his prior claim to invention, but he was, obviously, too late. It is important to note that there were two stages to the announcement of the “invention of photography:” first, there was a “disclosure” of the work of Daguerre in January of 1839 and then second, there was the actual public announcement with great fanfare made by Arago in August 1839. In order to strengthen his case, Talbot attempted to publish papers on his photographic experiments with the Royal Society, and Some account of the art of photogenic drawing was published early in 1839, but, for some reason, the Society was uninterested in publishing any of his other papers on his photographic processes. In his first paper, Talbot wrote that “This remarkable phenomenon, of what ever value it may turn out in its application to the arts, will at least be accepted as a new proof of the value of the inductive methods of modern science.” Next, again to make sure he was not overrun by the French excitement, Talbot returned to the task of improving his images, which he now dubbed “calotype,” meaning “beautiful print,” just the kind of unexacting term that Herschel would have disliked. His friends used the term “Talbotype,” a nice compliment, but hardly descriptive of the complicated process of capturing an image, printing the image and publishing the image.

However, in the 1840s Talbot had several problems he could not easily overcome. In contrast to Daguerre, who gave the knowledge of his process to the world, Talbot decided to protect his work, the “Calotype Photographic Process” with a patent in England in 1841 and in America in 1847. In a fast moving field where improvements were constant, the patent was a near useless protection. When he attempted to enforce the unenforceable, the court ruled in 1854 that, although Talbot was

… the true inventor of photography but ruled that newer processes were outside his patent. The acrimonious proceedings had stained Talbot’s reputation so severely that the prejudices raised continue to surface in historical literature.

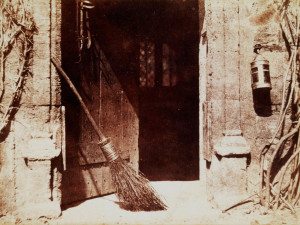

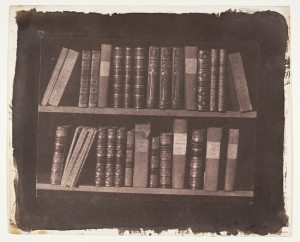

The next problem that Talbot faced was that his images were prints on paper. Using papers that were light sensitive, he could produce a paper “negative” which could then, through “contact” with another piece of light sensitive paper, make a “positive.” But since the image was on paper, the paper’s fibers interrupted the image itself. The smooth silvered plate offered by the Daguerrotype, in contrast, had no such obstruction and the image produced by Daguerre’s procedure were astonishingly smooth, fluid, precise, presenting a level of detail that the naked human eye could not see. Therefore, ironically, given that Talbot was a close friend of Herschel, the invention of Daguerre seemed better suited to the needs of science. Talbot, however, maintained that his process, regardless of the drawbacks of paper was superior to the unique Daguerreotype, due to the fact that his images could be reproduced. He was certainly correct, but with with his next attempt, a book of photographs, the first book of photographs, The Pencil of Nature (1844-6), Talbot discovered yet another issue–the public could not comprehend that photography could be an art form in and of itself and did not understand the concept of a book with photographs or as he termed them “photographic drawings.”

Whether or not Talbot was interested in the commercial application of photography is doubtful and that an artistic intention was the inspiration for The Pencil of Nature. It is more likely that the publication of this book was to demonstrate the superiority of his “invention” and to cement his claim as an “inventor” of photography. In the midst of his introduction to the book, Talbot, somewhat defensively wrote,

The Author of the present work having been so fortunate as to discover, about ten years ago, the principles and practice of Photogenic Drawing, is desirous that the first specimen of an Art, likely in all probability to be much employed in future, should be published in the country where it was first discovered. And he makes no doubt that is countrymen will deem such an intention sufficiently laudable to induce them to excuse the imperfections necessarily incident to a first attempt to exhibit an Art of so great singularity which employs processes entirely new, and having no analogy to any thing in use before.

In the second chapter of his book, Talbot staked his claim back to the days in Italy in 1833 and described in great detail the progression from the camera lucida to the mousetrap cameras. He carefully dated and described each event of his discoveries and mentioned his shock at the announcement in Paris and then proceeded to explain the variations of the tints of the prints–the differences in the intensity of the sunlight and the quality of the paper used–as if to preempt comparisons with the always uniform Daguerrotype:

These tints, however, might undoubtedly be brought nearer to uniformity, if any great advantage appeared likely to result: but, several persons of taste having been consulted on the point, viz. which tint on the whole deserved a preference, it was found that their opinions offered nothing approaching to unanimity, and therefore, as the process presents us spontaneously with a variety of shades of colour, it was thought best to admit whichever appeared pleasing to the eye, without aiming at an uniformity which is hardly attainable. And with these brief observations I commend the pictures to the indulgence of the Gentle Reader.

One of the problems that The Pencil of Nature and its successor, Sun Pictures in Scotland (1845) was the lack uniform quality of the prints (positives) and their continuous fading, even after publication, a sad inevitability that cheered painters who did not want competition from a mechanical camera. The Pencil of Nature was published in six installments between 1844 and 1846 (January, May, June, December, 1845 and April 1846) and due to lack of public response, future editions never materialized. That said, the book, with its twenty four plates, is designated as the “first mass-produced photographically illustrated book,” which is true, but that is a rather flat phrase for what was a very beautiful printed beautifully printed object in which the book itself becomes an art form. Each plate is accompanied by a brief description of the conditions under which the image was taken. Whereas it is clear in examining the photographs in the book that the arrangements are done with artistic intent and that the angles or framings were also selected with artistic intent in regards to composition, Talbot still understood his efforts to be a form of evidence of a scientific process. It should be understood, that at this early stage, photography, its intents, its effects, its purposes, and its future was then completely unknown to this inventor. Like all the experimenters with light, Talbot had little idea of what he had started. In the article, “‘Displaced Origins:’ William Henry Fox Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature” (2008), Vered Maimon wrote that

Talbot’s conception of the document, then, is aphotographic distillation of the evidentiary structure of positivism, of thecircular, naturalizing, self-confirming model of evidence shared by the moderndiscourses of science, history and law.’ The status of the photograph as a document therefore hinges on its ontology as a direct trace of nature–an index, yet it is also modeled on the evidentiary structure of positivism which was extended in the modern period to other forms of knowledge..For Talbot in The Pencil of Nature, the status of the photograph as a document and testimony oscillates between its capacity to copy, to accurately depict everything the camera sees (like a ‘legal’ or archival document), and its capacity to evoke the imagination by introducing unexpected ‘trivial’ details and therefore variety into what is often described by Talbot as a visually homogeneous surface.

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.