SCULPTURE FOR THE PUBLIC

Training and Execution of Sculptors

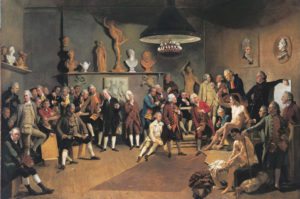

The most prestigious place to study, work, live and exhibit art was Paris, whether one was French or not. Nowhere was the system of education and training more rigorous. For the artists outside of Paris, there were numerous provincial art schools, écoles de dessin and académies des beaux-arts. By 1830, training for sculptors was similar to the training for painters in the rigorous control of style and content. The stress was on conformity and upon learning a certain set of technical skills that enabled the sculptor to produced the desired works in the official style. Drawing was the foundation of an artistic education learned at the Academy, and the artists would be trained later in painting or sculpture in ateliers or in studio courses taught by famous artists. Provincial sculptors could also study from drawing courses printed in Paris. Predating the later use of photography and textbooks, these unbound lithographed sheets of stipulated objects were copied by artists outside of the Academy. Called modèles estampes, these prints were for aspiring students, who could also work from plaster casts of existing sculptures, also available outside the Academy. The entire process of education was based upon the belief that copying a particular style, Classicism, was the appropriate way to learn one’s trade.

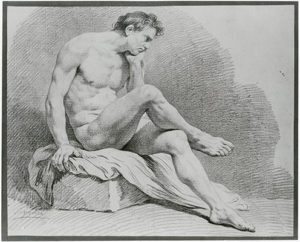

At the Petit école, a “school” that we today might be termed “trade” or “vocational,” students took courses in human anatomy, modeling and drawing. Reflecting the careful attention to the arts at all levels, courses in architectural history or in ornament trained students to supply the carved decorative motifs necessary for the building trade, which embellished architecture. In contrast, students, who wanted to focus on fine art sculpting went on to the École des Beaux-Arts where they were first granted the right of “inscription,” that is, the right to follow the courses to the right of “admission,” which gave the student the opportunity to participate actively in actual making. Once admitted, further proof of training was demanded in which students had to demonstrate their skills in competitions for admission in one of the two annual concours des places. These competitions for available slots in the Academy consisted of six three-hour sessions of drawing and modeling the figure from nature. These concours des places would be the equivalent of being admitted to an art school with a portfolio.

The schedule of the sculptor’s training followed that of the painter–from drawing outlines to drawing volumes before advancing to the drawing live models. Because these models were nude, women were excluded from the academies in order to protect their virtue. In France, women as sculptors were few and far between. During the first two years, students copied casts of antique marbles and began to work from life only by the third year. In the fourth year, the student was expected to complete a full-scale marble statue of a human figure. Once again, the sculptor would follow the same procedure as a painter, from drawing to sketch to study to finished product. First, the student would produce a drawing of the proposed work. Second, he would make a small model in clay or wax, a bozetto or maquette, which would be spontaneous and sketchy, rather like a rough draft. Next, a full-scale clay model would be made and then destroyed in the process of making a plaster cast of it. With the aid of the pointing machine, the original plaster would be copied in marble by professional carvers, or practiciens, or the plaster cast could be cast in bronze at the foundry. Thus there are no “originals” in sculpture, unless the clay model or the maquette is preserved. By 1851, this system of education and production was universal in sculpture.

A class at the Academy

Competitions among students never ended. The études libres or free studies, which presented two weeks of free study of specific problems set out by the professor prepared the students for the most prestigious competition of all, the Prix de Rome. The problems or topics were complex in nature, allowing the students to demonstrate mastery of technique. The screening process for the candidates included the première essai, a sketch of a pre-selected subject which eliminated all but sixteen students. These fortunate students returned for the deuxième essai, in which they sculpted, either in relief or in the round, a figure from a living model. Full-scale sculptures from the original sketches had to be produced in two months time, from themes that were usually taken from ancient history or mythology. The sculptural subject matter demanded by the Academy reflected history painting. Like history painting, sculptural works were destined for the larger community and the ultimate destination would be a large scale public work. The Prix de Rome was based upon the assumption that the only the aesthetic criteria was antique sculpture. These competitions, no matter how small or large, reinforced the academic doctrine of classicism on one hand and the enormous prestige of the École and its prizes. Although when he was a competing student Jacques-Louis David threatened to starve himself, when he lost in the Prix de Rome competition, the decision of the conservative judges was accepted and not debated.

The French Academy in Rome. View along the Via del Corso of the Palazzo dellAccademia, established by Louis XIV

The French Revolution and the Napoléonic wars that followed disrupted this careful schedule of education, training, and competition. One of those whose career was interrupted by the political unrest was François Rude (1784-1855) who, being from Dijon, would have grown up in the shadow of Claus Sluter’s Well of Moses (1400). Thanks to an admiring local patron, Rude was sent to complete his education in Paris where he won the Prix de Rome in 1812 to execute a sculpture he himself destroyed in 1843. Unfortunately, due to the expense of the ongoing conflicts, his academic education ended with what was a largely honorary prize and he never went to the Eternal City. Disappointed and derailed, Rude returned to Dijon in 1814 to escape the increasing political unrest associated with the downfall of Napoléon, but he made the mistake of joining the local Bonapartists. When Napoléon finally accepted defeat, Rude, like David, fled to Brussels. In leaving France, Rude missed the transition from Neoclassical sculpture, a tradition that had not produced many French sculptors of note, with the possible exception of David d’Angers. But when he returned to France in 1827, Rude returned as a sculptor inspired by the new Romantic tendencies, and new career opportunities would open for him.

From 1750 to 1800, sculptors had to create models of proposed monumental sculptors on their own initiative in hopes that critical acclaim would attract buyers. Unlike the painters whose materials, paint and canvas, were relatively cheap, sculptors were bound to the tradition of expensive marble and bronze. Commissions were, more often than not, public which immediately meant that the sculptor had to submit to a civic committee and lacked the same kind of freedom a painter, working alone, would have. Local patrons tended to be either restrictive or the themes could be limiting to artistic creativity. The result was that sculpture, as a discipline, lagged behind painting in innovation of means and content, simply because the sculpture had to suit the public’s brief. That said, the Industrial Revolution actually reduced the price of metal and sculptors could produce small bronze sculptures that were not only within the price range of the average art buyer but could also fit into a domestic decor.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, sculptors had learned to create on a smaller scale and thus unlike the sculptors of the early decades of the century, sculptors at mid-century were less dependent upon public patrons and the commissions they requested. Sculptor and actor Sarah Bernhardt was able to successfully execute in both marble and bronze, usually on a small scale. The aim of bronze casting was to capture the texture of the clay model and allowed the sculptor to take on a newly independent role, directly addressing a new rich bourgeois buyer. Initially Neoclassical sculpture enjoyed a prestige that was higher than that of painting, which was more “private,” that is, placed in museums. Public sculpture, which was out in the open and seen by everyone, needed to be in the Neoclassical style was intended to educate and inspire the public to strive for nobility in society. However, as times changed, sculptural monuments had to respond to the needs of this newly democratic and middle class society that wanted to see its own history commemorated.

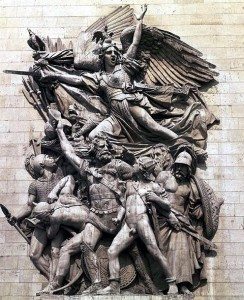

One of the more successful, if not the most successful public commissions of the first half of the nineteenth century, was The Departure of the Volunteers 1792 (1833-6) by François Rude. Affectionately known as La Marseillaise, the gigantic and dramatic high relief sculpture was mounted on the Arc de Triomphe (1803-36). At forty two feet in height, this tightly grouped segment of the common people who rose up during the Revolution is dynamic and exciting–full blown Romanticism. Oddly, if one assumes a reading of the reliefs on the flanks of the Arc, the left flank, The Triumph of Napoléon by Jean-Pierre Cortot, depicts an event more recent than that of Rude. But despite the quibble about chronology, La Marseillaise outshines the rather staid and unexciting example of waning Neoclassicism. In his book, Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815-1848, the late Albert Boime noted that the commission came from a post-Napoléonic Restoration government. Rude and the other sculptor, who did the reliefs for the other side of the Arc, Antoine Étex, were from working class families and were deliberately selected by Adolphe Thiers, who wanted to break the power of the Academy by selecting outsiders to realize his program of French history.

Despite the presence of other artists, the panel by Rude dominated and became a public favorite. Only he managed to rise above the out-of date adherence to Neoclassicism static poses by activating the common people in a state of patriotic fervor. Sweeping action figures make the relief seem to come alive, bringing back memories that in 1836 would have been still alive for many who gazed up at the carvings. Clearly Rude understood that the artist had to communicate with a diverse audience that demanded contemporary content and historical accuracy and a degree of realism that was incompatible with Neoclassicism. As Boime explained, the sculpture depicted a very specific event, the occasion when the National Convention called for an Army of Volunteers to march against the advancing Prussians and Austrians. To our modern eyes, the sculpture seems energetic, even frenzied, but Rude felt that he had compromised his vision for his benefactor and that the work was too “beautiful” to convey the true spirit of the times. Once the sculptor stepped into contemporary history, s/he had entered into the precincts of Romanticism and into lived and experienced history itself. Unfortunately Rude’s mobile life had left him outside the precincts of the Academy and he had to wait for the year of his death 1855 before the Institute would honor his achievements.

Also read: “The French Academy” and “The Artistic Revolution in France” and “The French Academy: Painting”

Also listen to: “The Academy and the Avant-Garde“

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.

[email protected]