Rephotographic Survey Project

Following Footsteps of the First Photographers

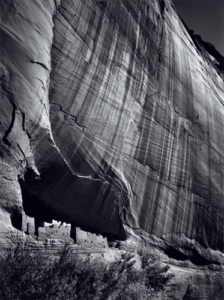

The idea of re-photographing the already photographed was not exactly a new one in the 1970s as evidenced by the re-photographing of Canyon de Chelly by Ansel Adams who stood in the shoes of Timothy O’Sullivan. But Adams did not intend to be a rephotographer. As he explained, “Only when I had completed the prints months later did I realize why the subject had a familiar aspect: I had seen the remarkable photographer made by Timothy O’Sullivan in 1873, in an album of his original prints that I once possessed. I had stood unaware in almost the same spot of the canyon floor, about the same month and day, and at nearly the same time of day that O’Sullivan must have made his exposure, almost exactly sixty-nine years earlier.”

Ansel Adams. Canyon de Chelly (1941)

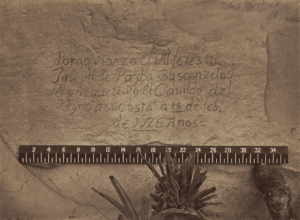

O’Sullivan himself had walked in the boots of the conquistadors who roamed through the western deserts. One anonymous soldier left an inscription carved on the face of a rock, marking his passage. In the same year he photographed Canyon de Chelly, O’Sullivan carefully placed a ruler to show the scale of the writing and then photographed the message of the Spanish invader.

Timothy O’Sullivan. Historic Spanish Record of the Conquest. South Side of Inscription Rock, New Mexico (1873)

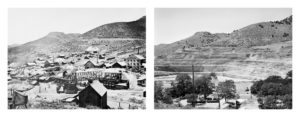

But with the rare exception of finding the traces of history, it was O’Sullivan, along with the other early photographers, Andrew Russell, Alexander Gardner, William Henry Jackson, all connected to survey parties and railroads, who recorded the second invasion of the land of Native Americans. Like the Spanish, the American corporations came to conquer, and, backed up by the government military, they were paving the way for white settlers and the displacement of the original inhabitants. But the 1970s rethinking and re-en-visioning of the land that continued with the work of the “Rephotographic Survey Project,” initiated by Mark Klett, researched by Ellen Manchester, along with the photographer JoAnne Verberg in the summer of 1977 had everything to do with history and nothing to do with the politics of Manifest Destiny. The original trio was joined later by Gordon Bunshaw and Rick Dingus. In fact, the RSP, dating from 1977 to 1979, needs to be understood, not in terms of the past but in terms of the contemporary backdrop against which photographers were acting.

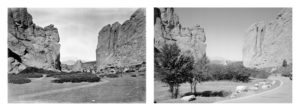

The Survey was systematic and investigative, with the historian, Ellen Manchester, and the re-photographers, Mark Klett, Rick Dingus and Jo Anne Verberg, functioned like detectives, tracking an operative. The project which, painstakingly relocated each site and determined the time of the year and even of the day and the position or framing selected by the first photographer, examined the choices and the decisions made by the photographer. When each photograph by a Re-Photographer was made from the exact camera and lens positions as the original photograph, the new image revealed not just the impact of time and modernization upon the land but also–possibly–the mindset of the photographer.

The result of this investigation was the book, Second View: The Rephotographic Survey Project (1984). Put in motion during the awakening of the contemporary environmental movement, the RSP was painstaking and meticulous but was viewed later as being an extension of a critique of westward expansion. The sense of a re-seeing of American history only became more acute with the re-writing of history from the standpoint of multiculturalism, including women and Native Americans in the traditional account. The words “virgin land” and “penetration” of the West, as well as the “taming” of the West were re-interpreted, not as benign descriptions of a process but as the sexist terminology of a phallic intent to conquer. By the 1980s, the notion of Manifest Destiny as a positive force that “won” the West was challenged by the new critique of racist policies that included deliberate genocides that preceded the incarceration of the Native Americans in reservations. It is with an expansive re-writing of history as the backdrop of the Project, which was led by Mark Klett (1952-), that the pairings of images can be evaluated. Among the earliest reevaluations of the ways in which the original inhabitants were cleared from their own lands was Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West by Dee Brown. This classic book, still resonant today, was published as early as 1970.

If Brown’s book stands as a moral judgment upon American actions after the Civil War, then the major form of critique during the eighties was Marxism, an economic analysis of the reasons for settling the West. In the chapter, “The Westward Route,” in his 1982 book, The Incorporation of America: Culture and Society in the Gilded Age, Alan Trachtenberg wrote,

An invention of cultural myth, the word “West” embraced an astonishing variety of surfaces and practices, of physiognomic differences and sundry exploitations they invited. The Western lands provided resources essential as much to industrial development after the Civil War as to cultural needs of justification, incentive, and disguise. Land and minerals served economic and ideological purposes, the two merging into a single complex image of the West: a temporal site of the route from past to future, and the spatial site for revitalizing national energies. As myth and as economic entity, the West proved indispensable to the formation of a national society and a cultural mission: to fill the vacancy of the Western spaces with civilization, by means of incorporation (political as well as economic) and violence. Myth and exploitation, incorporation and violence: the processes went hand in hand.

Trachtenberg’s critique joins the other critiques an economic perspective, Marxist in that the case of “exploitation, incorporation and violence” all of which were linked to economic imperatives. In other words, the term “Manifest Destiny” was an ideological cloak covering what was a single-minded imperative to “incorporate” the West, to turn the “undeveloped” spaces into economically viable sites contributing to the nation’s prosperity. The myth of the Old West which followed upon the heels of the Closing of the Frontier, further concealed the economic needs of the nation, attempting to recover from a ruinous Civil War. Historians of the late twentieth century noted that the nineteenth-century discourse of “destiny” as a justification for what were crimes against nature and the human beings who lived in the West managed to ignore that which was not hiding in plain sight: the racist and frankly bloodthirsty views towards the supposed subhuman and apparently uncivilized Native Americans. To the extent that the democratic nation experienced any cognitive dissonance the mindset of (internal) colonization papered over any sense of sin. The words “Manifest Destiny” hid a multitude of misdeeds because it was “manifest” as in obvious that it was the “destiny” of America to be joined coast to coast. And there was no shame in having monetary interests at the forefront if not as the very definition of “manifest destiny.” As Trachtenberg indicated, the quasi-religious connections between a pre-lapsarian state and the quest for the West, veiled monetary motives. He wrote that

“The overt aim of these early probings was to chart the way to an agricultural empire–a “new garden of the world”; they explored regions for settlement and military defense. Reflecting a different emphasis and a new set of needs, explorations during, the Civil War and continuing to the end of the century were concerned with natural resources; they were explicitly “scientific” expeditions, typified by the meticulously planned United States Geological Survey established in 1879. Such surveys collected detailed information about terrain, mineral and timber resources, climate, and water supply. One of the tangible products of the several postwar surveys were thousands of photographs, displayed in mammoth-sized plates and in three-dimensional stereo images, an astonishing body of work that when viewed outside the context of the reports it accompanied seems to perpetuate the landscape tradition. Many of the photographers, such as William Henry Jackson, clearly followed conventions of painting in depicting panoramic landscapes, while others, like Timothy O’Sullivan, worked more closely to the spirit of investigation of the surveys and produced more original visual reports. The photographs represent an essential aspect of the enterprise, a form of record keeping; they contributed to the federal government’s policy of supplying fundamental needs of industrialization, needs for reliable data concerning raw materials, and promoted a public willingness to support government policy of conquest, settlement, and exploitation.”

While there is nothing inherently wrong or evil about capitalization of an enterprise to industrialize and settle territory, the cost that so concerns us today–the destruction of the natural landscape and the decimation of the buffalo herds and the displacement of the native tribes and the destruction of the cultures of those peoples–were future events, unknown to the first survey teams. Certainly, those connected to the railroad lines pushing towards and through the frontier would have been witness to this original carving into the mountains and the prairie, but there is a question of whether it is proper to replace their perspectives with our own. That said, in these decades of reconsidering a once familiar history–the seventies and the eighties–the idea of “landscape” was under examination by photographers in the West. But once, again, these discussions need to be juxtaposed to the question of whether the original photographers were even thinking in terms of “landscape” an artistic or aesthetic trope. Indeed, it is more than possible they, like the railroad barons and the leaders of the survey parties, the photographers were acting in terms of “land,” a very different concept, implying an expansion of ownership in terms of real estate and profit. In fact, in the years before the Project began, Klett himself worked as a surveyor for the United States Geological Survey, trekking across Montana and Wyoming, seeking possible sources for that very polluting natural resource, coal. It was during this period of brief employment that Klett realized that earlier miners had been in the West more than a century before him. These initial attempts to turn land into profit had already been photographed, but what, in the 1970s, did their original images mean? As Klett realized, “Photos always seem to exist as sort of stuffy, unnecessary antiques that we put in a drawer — unless we take them out, put them in current dialogue, and give them relevance.”

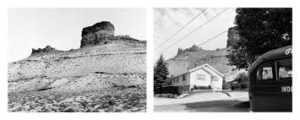

William Henry Jackson, Gateway Garden of the Gods, 1873 compared to

Mark Klett and JoAnne Verberg’s Gateway Garden of the Gods, 1977

The 1984 book revealed one hundred twenty pairs of images taken by the first photographer who originally “viewed” the western territory through the eyes of white men thinking of “opening” the vast spaces to colonizers. During the first year, the re-photographers retraced William Henry Jackson. Jackson had served in the Civil War and shortly after the war ended, he joined the Ferdinand Vandiveer Hayden survey which took him into the extraordinary world of Yellowstone. The subsequent section of the Project included the three photographers who had worked embedded, so to speak, with the Federal Army during the Civil War. Andrew J. Russell had recorded the work of military engineers and was ideally suited to follow the trek of the railroad running west, the Union Pacific. Timothy O’Sullivan and Alexander Gardner had spent the greater part of the Civil War documenting the fallen, strewn across the battlefields of the borders between the United States and the Confederacy. All of these photographers must have found the endless possibilities of the West, the wide open spaces, the broad sky, the endless sun, and the unindustrialized quiet of the plains a great source of solace after the noise and carnage of a war. Whatever their sentiments, the quartet set about their appointed tasks as professionals, acting under orders and all probably had more supervision than they had during the Civil War. O’Sullivan served under two government agencies, the geological survey expeditions of Clarence King and George Wheeler, and would have been expected to fulfill a particular brief.

“Repeat photography,” as it was first called, was based upon scientific bases: to recreate faithfully and to reveal the original state of the scene. However, Klett was not attempting to see as the first photographers viewed the land, His position was that it was important “to see them in our own terms.” In other words, Klett was recording change, whether through wind, water or weather or through human intervention. We can only see the world from our own vantage point. So the view is double: the past and the present are juxtaposed in dual visions of the West. It says a great deal about the still experimental and comparatively primitive state of photography to realize that the working methods of Mark Klett had to faithfully reproduce the methods of photographers who often made their own cameras, ground their own lenses and employed a variety of safeguards to protect the plates in hostile environments. For example, a photographer might have stood on a particular place that no longer exists due to development or natural erosion or the position and framing selected has to also take into account which lens was used. In addition, unlike Jackson who took the first photographs of Yellowstone, the photographers were often taking note of exploitation of the land, such as mines, already underway, careless use that would cause the environment to deteriorate over time. By the late 1860s, the corporate probes are already in place and even Jackson winds up watching the railroads wind around and under seemingly impassible mountains. HIs images of American engineering, feats undoubtedly hone during the recent war, show an impressive mastery of nature that must have been inspiring to all who saw these images.

One hundred years later, the rephotographers, guided by the historical work of Ellen Manchester, arrived on the scene. It is interesting and probably significant that the team was led by a geologist, Klett, who was acutely aware of time. But can time be seen and can its trail be found? The body of the paired photographs presented sometimes surprising answers. As the essayist for the Second View book, photographer Paul Berger, remarked, “The first thing you think about in the pairs is the before and after aspect. You expect a hundred years is a lot of time, there should be some difference or you overlay the idea that it must have been more pastoral then, or that it used to look nice then and now it’s all screwed up or whatever–stereotypical ideas about what a hundred years would show. In fact, when you look through them, they’re really all over the place. There are a few where there is almost no change or the change is almost insignificant (the picture with a missing boulder), some actually reverse what you might expect, and there are a couple of ironic pictures, such as one where the picture is virtually identical but the name of the lake and the mountain had been changed. Some of them start to look strange because the contemporary picture looks like an odd photo, one you wouldn’t choose to make. Which then becomes another irony, because that seems like a very contemporary thing to do, to obscure the composition.”

As Berger pointed out, it is not change–of nature itself, of the site, of the state of the environment– that is being found by the rephotographers but the choices made by the original photographers who were tasked with photographing the West. As pointed out in previous posts, either consciously or unconsciously, these artists would have had a built-in visual vocabulary derived from landscape painting, but the West thwarted any preconceptions. At most, the West could fit into the category of the “sublime.” But the survey photographers had more mundane instructions: documentation without drama. The next post will continue to discuss the process of photographing the already photographed.