ART AND THE MODERN PUBLIC

The Birth of Modern Patronage

Spanning the seventeenth and eighteenth Centuries, the Enlightenment produced greater philosophical thinking than it did great works in the fine arts. In other words, new ideas and “progress” did not prevail in an art world dominated by aristocratic patronage and clientele. That said, the Enlightenment was crucial for a new way of thinking about art and art making. For Europe and the fledgling nation of America, “art” was a practice established in France. All other nations follow suit and followed French styles. In the beginning of this period of change and development of new kinds of individuals, newly free and newly equal, the production of visual art was under the protection and sponsorship of the State, under the censorious auspices of the Royal Academy, established in 1648 by the French King Louis XIV. This Academy of arts and letters was a model of central control followed by other major nations, all of which were aware of the need to monopolize the arts and to harness them to the needs of the government. Because the people of France paid for the education of artists, the French government, the major sponsor of art, held Salons, or public exhibitions of state-sponsored art from the eighteenth century. Set up outside on the grounds of the Palais Royale the new home of the Duc d’Orleans, who had an appetite for beauty and pleasure and the visual arts, the Academy showed off the achievements of the leading artists. But after the first show in 1704, this site of balls and fêtes proved unsuitable for large public exhibitions and the later salons were held at the Palace of the Louvre.

However, there was a real world for artists that existed and this world had little to do with the changes that the Salon exhibitions would bring to the French artists. French artists were essentially commercial artists, working for the wealthy and well to do and for the aristocrats.The definition of “art” was what the patron wanted. The definition of “success” wa that the patron accepted and paid for the finished product. Art was a business, conducted between buyers and sellers, without juries or critics holding meta judgments over the heads of the artists. In her book French Art of the Eighteenth Century: The Michael L. Rosenberg Lecture Series at the Dallas Museum of Art, Mary Tavener Holmes wrote about the art world,

Paris in the mid-eighteenth century was the most glittering and influential capital city in Europe, until everything came crashing down with the Revolution of 1789. The taste in interior decoration became more intimate and lighthearted than in the great rooms of Versailles. Artists by and large provided a decorative, rather than didactic kind of painting. Eighteenth century Paris was still a place where artists worked mainly on commission, or at least with a specific market in mind. One may have a very romantic conception of the artist working in his studio, expressing his view of he world. But artists at that time were not concerned with exploring their subjectivity or expressing their personal vision of the world. In other words, artists were socially integrated and played an important role in the luxury goods market of Europe..Antoine Watteau’s Shop Sign is a classic depiction of the luxury goods market in Paris for which artists worked. It’s an imaginary view of the scope of the luxury goods dealer Edmé-François Gersaint. The interior features various men and women coming and going, perusing the works and each other. At the left, the portrait of Louis XIV is being put away in a crate. A man is lifting down a mirror and he shop is full of ornately framed pictures. There’s a young woman examining a vanity case. At center is an old man scrutinizing carefully some nudes in a landscape picture.

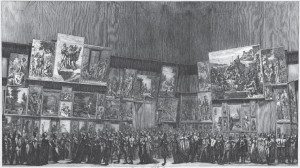

Until the major exhibitions in the Louvre, which were open to the public, that is those who were not the nobility that usually graced the always of the Palace. More to the point, once the non-aristocracy enters, the tenor of viewing changes, for the middle class is not necessarily a patron class, at least not at this time. They are invited, not to purchase or to plan home decoration, but to “appreciate” the art on display. Once such an invitation is extended, then appreciation immediately extends to “critique.” Here in the Palace the works of art could be protected from the weather and were displayed to their best advantage, albeit hung from floor to ceiling and packed chock a block on tables crowded in limited floor space. The Salons were held every year or every other year after 1737 on August 25th in the Salon carré of the Louvre. These highly popular events ran ten days to four weeks, attracting the art public and the art critic, both new social entities, which according to Thomas Crow’s Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth Century Paris (1987), where feared and hated by the artists. The Salons were Parisian events that were considered public entertainment on one hand and a display of the will of the state on the other, demonstrating, through works of art, lessons that every good subject should be taught. These exhibitions, which preceded the establishment of museums, were forms of disciplining the people and shaped their behavior in public places, establishing modes of “civilized” behavior. What was less anticipated by the government or the artists, much less by the Academy itself, was the enthusiasm with which the public embraced these events. Suddenly otherwise uneducated people developed opinions and some were bold enough to state their reactions to the art in what rapidly became a two-way conversation between the servants of the State and the public.

Thomas Crow elegantly posed the problem that showing “art” to the “public” posed for the artists and for the state itself. “There was in this arrangement, however, an inherent tension between the part and the whole: the institution was collective in character, yet the experience it was meant to foster was an intimate and private one. In the modern public exhibition, starting with the Salon, the audience is assumed to shared in some community of interest, but what significant commonality may exist has been a far more elusive question. What was an aesthetic response when divorced from the small community of erudition, connoisseurship, and aristocratic culture that had heretofore given it meaning? To call the Salon audience a “public” implies some meaningful degree of conference in attitudes and expectations; could the crowd in the Louvre be described as anything more than a temporary collection of hopelessly heterogeneous individuals? This was the question facing the members of the art world of eighteenth-century Paris.”

The concept of a “public” for art was new as was the idea of publicaly exhibiting art, and inevitably, someone from the undifferentiated “public” would emerge with a desire to preserve and publish his or her opinion about art. This opinionated member of the public who dared to speak and write an to publish views about selected works, much to the dismay of the artists, was the “art critic.” By exposing the artists to the public, these annual Salons opened the artists to public scrutiny and public criticism and made the artists vulnerable to this new species, the art critic, who, astonishingly, demanded that the artist be accountable to the public. Artists, previously answerable only to elite groups of collectors and fellow artists, now needed public approval to succeed. The public, then as now, encompassed all levels of social and economic classes and all levels of education and constituted a community of interest, breaking social hierarchies down into the new notion of a “public,” as explored by Crow, who remarked that “the ‘public’ is both everywhere and nowhere in particular.” The creation and existence of this public brought with it new problems for the artist: what to represent in terms of subject matter; how to represent in terms of style; and who should be allowed to represent and who was allowed to speak to and for the public?

Also new was the expanding group of private art collectors who became the chief patrons of modern artists. Patronage was split between the aristocrats, such as Madame de Pompadour, and the newly rich middle class which preferred genre painting, that is, scenes of everyday middle class life, over the more prestigious and aristocratic history painting, depicting noble heroes of the distant past. As Rochelle Ziskin pointed out in Sheltering Art: Collecting and Social Identity in Early Eighteenth-century Paris (2012), art collecting became a sign of wealth and taste, a site of political and social rivalries and a means of constructing a public image. During this period of art collecting, several important large collections came on the market, such as the works owned by Queen Christina of Sweden, acquired by the French banker and art connoisseur, Pierre Crozet. Through these expanding collections, contemporary French artists were exposed to a historical spectrum of Western art and had a wide range of artistic possibilities to choose from when considering their mode of expression.

Despite the presence in France of the classical Baroque styles, the Baroque was systematically toned down in its dark dramas and was softened into pastel colors for the civilized and essentially domestic style of “Rococo” for an elegant French audience. Although much of Rococo art was produced for the aristocrats and rulers of Europe, the style was paradoxically involved with the concept of the “natural,” a reaction against the formality of aristocratic society and its artificial and unnatural mores and manners. Designed for the interior decoration of the new Parisian hôtels, the pale colors and gentle brushwork of the Rococo artists and the romantic themes made the paintings ideal for the domestic interiors of those who could afford them. But during the same period, the public taste for middle class scenes made genre artists, such as Jean-Baptiste-Simone Chardin (1669-1779) and Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1806), famous for their depictions of everyday life within the newly aspirational middle class in France. By the middle of the Eighteenth Century, a privilege visitor could peruse private art collections and enter the nascent art shops, selling supplies and pictures, and see, with perfect foresight a painted battleground of class and class aspirations.

Fragonard. The Progress of Love (1771–72)

Now in the Frick Collection, the panels of “Love’s Progress” or “The Progress of Love” executed by Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806) on behalf of Madame du Barry for her chateau at Louveciennes delightfully demonstrated the non-productive pastimes of the privileged. The privilege of leisure time allowed the upper classes to pursue their erotic desires in elaborate ways. It goes without saying that, for the lower classes, such spare time did not exist, linking the idea of romantic love to the upper classes, and thus attaching love to wealth. Sadly, Madame du Berry chose another artist, Joseph-Marie Vien, to do the same theme in the new Neo-Classical style, and the “Progress” was never installed. Thus we do not know its order but the four paintings are lined up as The Pursuit, The Meeting, The Lover Crowned, and The Love Letters.

Greuze. Broken Eggs (1756)

The middle class, growing in numbers and in social prominence, did not stress love and courtship, and indeed, there were didactic scenes aimed towards sober industrious people preaching the perils of indiscriminate delights. One of the most theatrical of lecturers was Jean-Baptiste Greuze whose small paintings of domestic tableaux demonstrated the dangers of bad behavior. Less theatrical and more absorbed, to borrow the lagrange of Michael Fried’s Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (1976) the small quiet interior studies of bourgeoisie life by Chardin were beloved by the Salon crowd and acquired by sophisticated collectors. Eschewing Greuze’s heavy handed didacticism, Chardin scarcely intended to convey a morality tale but the contrast between The Prayer Before the Meal (1740) and Fragonard’s provocative The Swing (1767) could hardly have been clearer. The two paintings, one public and one private, foretold the class conflicts to come and the revolution that would unfold in the next decades. One class was frivolous and irresponsible, the other class was moral and rational. Who deserved to be in power?

Fragonard. The Swing (1767) Chardin. Prayer Before the Meal (1740)

Also read: “What is Modern?” and “The Enlightenment: Introduction” and “The Enlightenment and Reason” and “The Enlightenment and Society” and “The Political Revolution in America” and “The Enlightenment and Artistic Styles”

Also listen to: “What is Modern?”

If you have found this material useful, please give credit to

Dr. Jeanne S. M. Willette and Art History Unstuffed. Thank you.

[email protected]